Early on in your Japanese studies, you’ll have been exposed to the wonderful mystery of Japanese adjectives. We’re usually taught that there are two kinds: い-adjectives and な-adjectives, each of which are named after the hiragana character they end in when they appear before a noun. For example, in 美しい景色 (pretty scenery), 美しい ends in い, and in きれいな人 (beautiful person), きれいな ends in な. Simple enough, right?

This mixing and matching of different word types undoubtedly leaves you with some questions: When do we use な and の? Are な and の interchangeable?

However, when we take a closer look at な-adjectives, things start to get a little tricky. Some words that you’d expect to take な, such as 病気 (sick), actually tend to take の before a noun, as in 病気の人. Look this up in most Japanese-English dictionaries, and you’ll see it listed as a の-adjective. Even weirder, some words, such as 真実 (reality), are even listed as a noun, な-adjective, and の-adjective.

This mixing and matching of different word types undoubtedly leaves you with some questions: When do we use な and の? Are な and の interchangeable? Does the choice between の and な change the meaning of the sentence?

Fear not, dear reader. In this article, we will answer these questions one step at a time. We will cover what な and の actually do when modifying a noun. We will explain why certain words tend to take な or の more often, and what happens when you choose the more uncommon of the two. After reading this article, you will have a better grasp on the meaning of な and の, and how to choose between them to say what you want to say, and say it well.

- The Basics of Noun Modification using な and の

- The Adjective ↔ Noun Spectrum

- 〜な気分 For When You’re in a Mood

- 終わりな気分

Prerequisites: This article assumes you already know hiragana and katakana. If you need to brush up, have a look at our Ultimate Hiragana Guide and Ultimate Katakana Guide. Beginners who are starting to learn about adjectives can enjoy reading this article, but to get most out of it, the basic knowleadge of な-adjectives and a particle の would be a nice-to-have. If you haven't already, we also recommend installing a text translator plug-in for your browser, such as Rikaikun or Safarikai. This article is a bit kanji-heavy, and having a hover-over translator might be nice to have!

Heads up: we also recorded a podcast episode about this topic on な-adjectives and の-adjectives. In it, we have some exercises for you to review what you're about to read, so we highly recommend listening to it after reading this article.

If you haven't yet, please subscribe to the Tofugu podcast and check out our other episodes there!

The Basics of Noun Modification using な and の

To begin our exploration of な vs の, we first need to talk about what “noun modification” is, and how な and の are used for different kinds of noun modification.

So first, what is noun modification? Put simply, it’s using another word (often, but not always, an adjective) to give more information about that noun. For example:

- きれいな人

- beautiful person

In this example, the noun 人 (person) is being modified by the な-adjective きれい (beautiful), which tells us a characteristic or quality of the person (that they are beautiful). This type of noun modification is called “describing”, and is typical of both い-adjectives and な-adjectives. So, when a な-adjective is used to describe a noun, it uses な to do so.

Now let’s examine what noun modification looks like when we use particle の, rather than な:

- きれいのヒント

- beauty hints

In this example, the noun ヒント (hint) is being modified by きれい, just like in the first example. This time though, きれい is followed by の. If you’ve learned anything about particle の, you might know that it is used to express the relationship between two nouns. In our English translation of きれいのヒント, you can see that きれい is translated as “beauty” (a noun), rather than “beautiful” (an adjective), as it was in the previous example.

な is used when you want to describe a noun, and の is used when you want to label a noun.

Wait — So if きれい a noun in this example, how is it able to modify another noun? As it turns out, nouns can modify other nouns, but in a different way than な-adjectives. Adjectives describe a quality or characteristic of a noun, whereas nouns label other nouns, telling us the type or category. So in our example, きれい does not describe ヒント (i.e. the hints themselves are not beautiful), it is telling us about the type of hints at hand. In other words, it helps us know that the hints are about beauty, not finance or dating. We'll call this type of noun modification “labeling”, and の is frequently used to express this.

To quickly sum up, な is used when you want to describe a noun, and の is used when you want to label a noun.

The Adjective ↔ Noun Spectrum

With that knowledge of noun modification (describing vs labeling) under our belts, let’s take a closer look at the な-adjective word type. As we saw above, きれい can take either な or の, straddling the boundary between adjectives and nouns. In fact, linguists refer to な-adjectives as “adjectival nouns” and “nominal (noun-like) adjectives”, since so many can transform from adjective to noun based on whether な or の follow them.

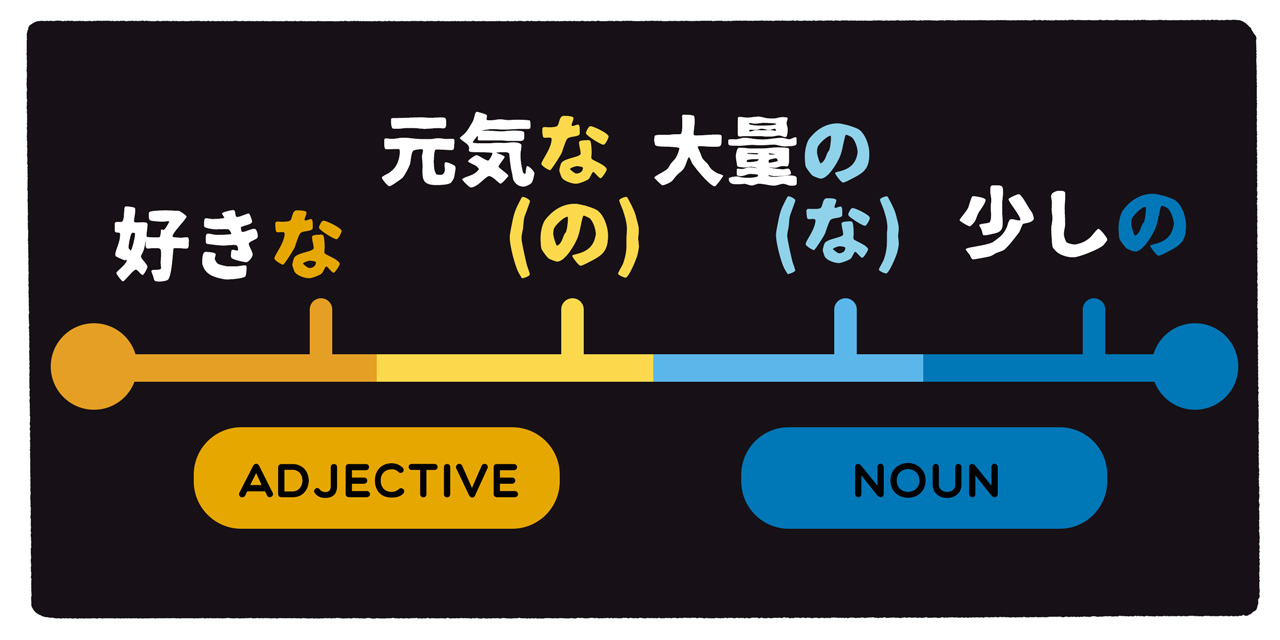

When individual words are examined, it becomes clear that most な-adjectives tend to be used more frequently in one way or the other — some tend towards use as adjective-like descriptors (and we think of as the typical な-adjectives), while others tend toward the noun-like label use (and are sometimes called の-adjectives in dictionaries and textbooks). For this reason, we like to think of these words as existing on an adjective ↔ noun spectrum, as you can see in the image and the chart below.

| Usually take な | な>の | の>な | Usually take の | |

| 好き | 困難 | 元気 | 大量 | 少し |

| 簡単 | 苦手 | 健康 | 病気 | 本当 |

| 大切 | 危険 | 安全 | 最高 | 永遠 |

| だめ | 嫌い | 美人 | 普通 | 最大 |

| 静か | 無理 | 不思議 | 未定 | たくさん |

| 大変 | 異常 | 平和 | 独自 | 真実 |

| すてき | 正直 | 幸せ | 最速 | 一杯 |

| 勝手 | 親切 | 不幸 | 一流 | |

| 複雑 | 残酷 | 不安 | 個別 | |

| 妙 | 有能 | 高級 | 固有 | |

| 正確 | 冷静 | 平等 | 別 | |

| 変 | 真剣 | 無名 | ||

| 必要 | 慎重 | 未知 | ||

| 深刻 | ||||

Words that are most frequently used with な as adjectives, such as 大切 (important/importance) and 便利 (convenient/convenience), are placed on the far left of the spectrum. On the far right, you’ll find words that are most frequently used with の as nouns, such as 本当 (true/truth) and 永遠 (eternal/eternity). Words that get used as both adjectives and nouns are found in the middle of the spectrum (but even these tend to favor one use over the other). In the next few sections, will take a deeper look at the words on left, right, and center of the spectrum, noting characteristics of each to help you gain confidence in choosing between な and の in your own Japanese.

な: The Adjective Side of the Spectrum

Words that tend towards the adjective side of the spectrum, such as 簡単 (simple) and 静か (quiet), are most frequently used with な to describe qualities or characteristics of nouns. These words will typically be listed as “な-adjectives” in Japanese-English dictionaries.

- 草取りはすごく簡単な作業だと思っていたけど、実は大変です。

- I thought that pulling weeds is a super simple task, but it’s actually terrible.

- 森に囲まれた、とても静かな環境に暮らしています。

- I live in a very quiet environment, surrounded by the forest.

In the first example, 簡単な describes a quality of 作業 (task). Similarly, 静かな describes the quality of 環境 (environment) in the second example. Neither adjective can be thought of as a label here, since they are based on a description of the speaker’s subjective or personally felt experience of the noun. While a label is meant to tell us what type of noun we’re talking about, a descriptive adjective simply embellishes the noun to add a more specific meaning.

Descriptive な-adjectives can usually be modified themselves, by an adverb of degree. Take a moment to examine the underlined word just before the な-adjective in each sentence. In the first, we see すごく (super) and in the second we see とても (very). These are both adverbs of degree, meaning that they tell us just how simple the task is, and just how quiet the environment is. A few more examples of degree adverbs are ちょっと (a little), かなり (fairly), and あまり (not very).

の: The Noun Side of the Spectrum

Words that tend towards the noun side of the spectrum are usually used with の to label the noun that they modify. These are the words that you’ll see listed as a “の-adjective” in many Japanese-English dictionaries. Words on this side of the spectrum can be loosely divided into two groups: words that express absolutes, like 本当 (true) and 最大 (the biggest), and words that express quantities, like たくさん (many) and 大量 (large amount).

Let’s start with a closer look at these nouns that express absolutes:

- 恋人ができない本当の理由を知りたい?

- Do you want to know the true reason no one will date you?

- 歯を失う最大の原因は歯を磨かないことです。

- The biggest cause of tooth loss is not brushing your teeth.

In the first example, 本当の labels the noun 理由 (reason) - it tells us that the reason is the truth, as opposed not the truth. In the second example, 最大の labels the noun 原因 (cause) — it tells us that this is the biggest, most significant cause, and we all know there can only be one biggest cause of something.

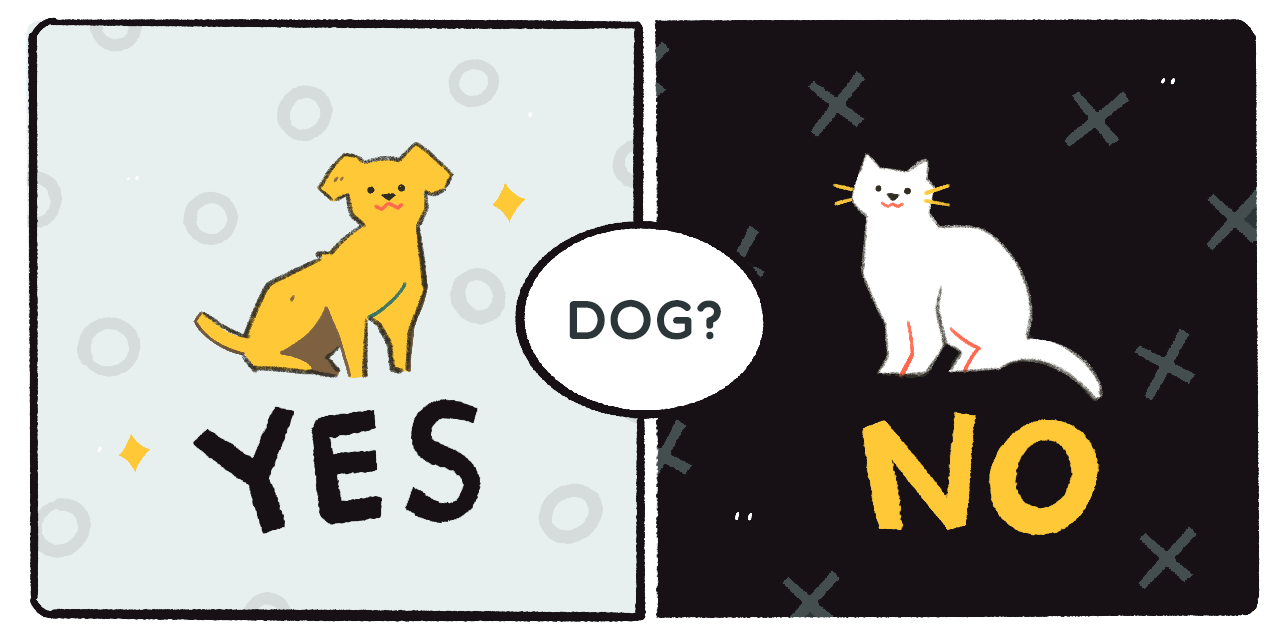

Something either is or isn’t a dog, is or isn’t true, and is or isn’t the biggest.

The fact that 本当 and 最大 are acting as nouns here might be hard for English speakers to see, since “true” and “biggest” are adjectives in English. Here’s the logic behind it — just like a more recognizable noun like “dog”, these words express absolutes. Something either is or isn’t a dog, is or isn’t true, and is or isn’t the biggest. That’s not the case with words on the adjective side of the spectrum, like 静か (quiet). While it’s quite possible to say ちょっと静か (a little quiet), the lack of a gray area for absolutes like 最大 means they generally can’t take adverbs of degree like とても (very) or ちょっと (a little).

However, there are plenty of words that tend to take の when modifying a noun that can take an adverb of degree. These include words that express quantities, such as たくさん (many) and 大量 (large amount):

- 昨日すごくたくさんの魚が釣れました。

- I was able to catch incredibly many fish yesterday.

- 電源が切れた途端に、かなり大量のデータが消されてしまいました。

- Right when the power ran out, quite a large amount of data was erased.

In the first example, たくさんの labels the noun 魚 (fish) — it tells us that this is “a lot of fish”, rather than “not a lot of fish”. Likewise, 大量の labels the noun データ (data) — it tells us this is “a large amount of data”, as opposed to “not a large amount of data”. By using の rather than な here, the quantities expressed are treated like objective facts. Anyone who looked at the fish or the data would agree, there’s a lot!

However, quantities are inherently gradable; if we add more fish to たくさんの魚, then it would be fair to use an adverb of degree like すごく (incredibly) to say すごくたくさんの魚. This is why you’ll see that we’ve included such adverbs in our example sentences above.

な or の: The Middle of the Spectrum

As this is a spectrum, there are many words that fall in the middle, and can take な or の. These words tend to have subtle shifts in meaning when one な or の is chosen over the other. In most cases, one use is still more frequent than the other, which is why you’ll see them slightly to the right or left on the spectrum table above.

Let’s kick this off with a discussion of 普通 (normal). This word usually finds itself placed on the の side of the spectrum, but using it as a な-adjective is possible too. To understand how the meaning shifts when used with な or の, let’s imagine a scene. Your sister has a new boyfriend, and he looks familiar, like maybe you’ve seen him on TV. Being the annoying little sibling you are, you start asking those pesky questions:

- 新しい彼氏、有名人なの?

- Is your new boyfriend a famous person?

- ううん、普通の人だよ。

- No, he’s a normal person.

Bummer, looks like he’s not famous after all! In this exchange, your sister chooses to answer your question by calling her boyfriend 普通の人. This is because she treats “normal” as a label for a type of people, and suggests that her boyfriend belongs in that category. While 普通な人 would not sound too outlandish here, it still would suggest that she’s describing his personality as normal. Let’s check out one more exchange, where な would sound more appropriate:

- 新しい彼氏、変な人なの?

- Is your new boyfriend a weirdo?

- ううん、普通な人だよ。

- No, he’s a normal person.

This second question was less about labeling the boyfriend or putting him into a category, and more so a question about his own personality. For this reason, your sister chose to use 普通な人 to describe him, highlighting normalness as a trait that characterizes him. 普通の人 is possible here too, if we decide to treat “weirdos” and “normal people” as categories of people, and assign membership to one or the other.

This system of な vs の applies to many words that fall in the middle of the spectrum, such as 病気 (sick). Generally, Japanese textbooks will tell you that you should select の with this word, and usually, that’s the safest bet. But the truth is, it can take な as well. Let’s see both uses in context to paint a clearer picture:

- その施設には、病気の人が多い。

- There are many sick people at that institution.

- その施設には、病気な人が多い。

- There are many sick people at that institution.

In the first example, 病気の modifies the noun 人 (people) through labeling. It tells us that the sentence applies to people who have a disease, as opposed to people who do not. This is the typical way that 病気 is used to modify nouns, and has the neutral, objective tone that is characteristic of labeler with の.

On the other hand, the second example features 病気な, which modifies 人 through description. In this (possible, but uncommon) use, 病気 is treated as a quality or characteristic of those people, which sounds negative — rude even. It sounds something akin to “sick in the head” in English.

You can apply this system to many words on the spectrum. As you encounter these differences in use out in the wild, think back on how な vs の affect the meaning in a nuanced way, and you’ll be able to better understand the intention of the speaker or writer.

〜な気分 For When You’re in a Mood

One of the best things about language is that it can be used in creative ways. The fact that nouns and adjectives exist on a spectrum allows us to do interesting things with these words, such as totally flip the script and use unexpected nouns in adjective-like ways. One place this is happening more and more is in social media, with the phrase 〜な気分.

気分 is a noun itself, which means “feeling” or “mood”. You might have learned it in common phrases such as 気分がいい (I’m in a good mood) or 気分が悪い (I’m in a bad mood). Let’s take a look at some interesting ways 〜な気分 is used by native speakers of Japanese:

For Cravings

Food and drink nouns can transformed into adjectives when paired up with 〜な気分. This allows you to express cravings and desires for specific beverages and dishes.

For example, ワインな気分 can be a perfect hashtag for images featuring glasses of wine, people toasting with one another, and tables of delicious meals. It’s used in a similar way as “I’m feeling like wine tonight” or “It’s a wine kinda evening” in English.

For Self Expression

Have you ever been in the mood to wear a certain color, or express a certain look? Colors, styles, and fashion choice nouns are often used as adjectives with 〜な気分. Check it out:

90年代な気分 could be used if you wake up feeling like you really want to look like a blast from the past. “The 90’s” is a noun, but you can use this phrase to say “I’m feeling really 90’s today”.

For Places and Activities

Another use of 〜な気分 is to express your desire to be in a particular place or do a particular activity. For example:

海な気分 is used in a similar way that we might say “feeling those beachy vibes” in English. You might see it captioning a picture featuring palm trees and blue skies, or perhaps describing a particularly summery outfit. You might even say it if you wake up on a super sunny day, and have an urge to go hit the beach.

終わりな気分

If you’ve made it all the way to the end, congratulations! Now you know that Japanese adjectives and nouns exist on a spectrum, which explains why they can take な and の in different contexts and situations. な suggests that the word is a description, whereas の tells us that it is labeling another noun. As you go out into the world and see な-adjectives and nouns acting in unexpected ways, you’ll have the tools to analyze these instances and understand the meaning on a deeper level. それでは、素敵な一日を!