The Nine Intelligences: by itself the term sounds like an elite spy group or a color-coded hero team.

“Gentlemen, we’re clearly in over our heads. The world is in danger. Only The Nine Intelligences can save us now!”

Although the nine intelligences aren’t a super hero team, they saved me on countless occasions – only under totally different circumstances. Boring textbook have you cornered? Give them a call! No ideas on how to teach a topic? They can lend a hand!

Like a secret weapon, I call upon this educational theory in times of trouble. When my mind goes blank, the creativity well runs dry and lesson plan ideas are few and far between.

Although originally intended to quantify learning styles and help all students find success in the classroom, the nine intelligences – part of Multiple Intelligence Theory – can also be used to add variety to lesson plans. And since the theory can be applied to any age group, in any subject – all teachers, regardless of their situations, can benefit from using it.

History

The real hero, Harvard professor Howard Gardner, formulated Multiple Intelligence Theory in the 1970s and published his findings in the groundbreaking book Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences in 1983. And he hasn’t looked back since, defending and refining his theory to this day.

According to Mr. Gardner, Multiple Intelligence Theory started as a response to the introduction of IQ tests, uniform curriculums, and other “one dimensional” educational practices – particularly those that aimed to gauge intelligence. Mr. Gardner writes:

Some years ago it occurred to me that this supposed rational (of a single, quantifiable intelligence) was completely unfair. The uniform school picks out and is addressed to a certain kind of mind… But to the extent that your mind works differently… school is certainly not fair to you (5).

Gardner contends that since individuals’ strengths and weaknesses vary, everyone thinks and learns differently. As a result, uniform tests and curriculums fail to accurately measure a student’s true intelligence and capabilities. He implored his readers:

Let your thoughts run freely over the capabilities of human beings… Your mind may turn to a brilliant chess player, the world-class violinist, and the champion athlete… Are the chess player, violinist, and athlete ‘intelligent’ in these pursuits? If they are, then why do our tests of ‘intelligence’ fail to identify them?… What allows them to achieve such astounding feats? In general, why does the contemporary construct of intelligence fail to take into account large areas of human endeavor? (6).

Gardner challenged contemporary ideas of intelligence by considering successful, evidently intelligent people that scored low on the tests – or more accurately, that the tests had failed to recognize. He contended that people were intelligent in different ways, ways the tests and “uniform schools” failed to evaluate or perceive.

I believe that human cognitive competence is better described in terms of set abilities, talents, or mental skills, which I call intelligences. All normal individuals possess each of these skills to some extent; individuals differ in the degree of skill and in the nature of their combination. (6)

Gardner quantified these intelligences in multiple intelligence theory. Although Gardner’s original theory featured only seven intelligences, he later expanded the count to nine. As an ever evolving theory, Gardner contends that if discovered, more intelligences can be added.

Without Further Ado: The Nine Intelligences

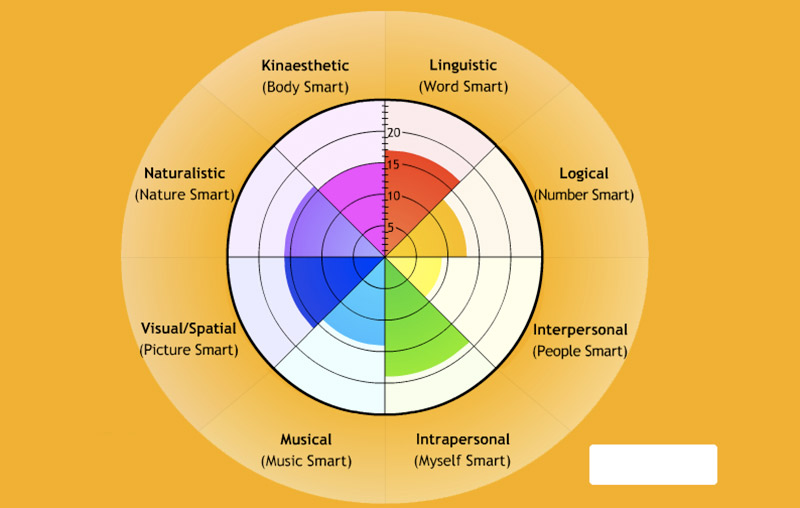

Gardner’s original seven intelligences included visual-spatial, body-kinesthetic, musical, intra-personal, interpersonal, linguistic, and logical-mathematical categories. Years later he added naturalist and existential intelligences to make a total of nine intelligences. Multiple intelligence theory devotee Dr. Thomas Armstrong provides a concise summary of the nine intelligences, which I have streamlined for this article, in his book, “Multiple Intelligences in the Classroom.”

Visual-Spacial Intelligence: the ability to think in three dimensions, graphic and artistic skills, and an active imagination. Sailors, pilots, sculptors, painters, and architects all exhibit spatial intelligence. Young adults with this kind of intelligence may be fascinated with mazes or jigsaw puzzles, or spend free time drawing.

Body-Kinesthetic Intelligence: the capacity to manipulate objects and use a variety of physical skills. This intelligence also involves a sense of timing and the perfection of skills through mind–body union. Athletes, dancers, surgeons, and craftspeople exhibit well-developed bodily kinesthetic intelligence.

Musical Intelligence: the capacity to discern pitch, rhythm, timbre, and tone. This intelligence enables us to recognize, create, reproduce, and reflect on music. Interestingly, mathematical and musical intelligences may share common thinking processes. Young adults with this kind of intelligence are usually singing or drumming to themselves.

Interpersonal Intelligence: the ability to understand and interact effectively with others. It involves communication, sensitivity to the moods and temperaments of others, and the ability to entertain multiple perspectives. Teachers, social workers, and politicians exhibit interpersonal intelligence. Young adults with this kind of intelligence are leaders among their peers, are good at communicating, and understand others’ feelings and motives.

Intrapersonal Intelligence: the capacity to understand oneself and one’s thoughts and feelings. Intra-personal intelligence involves not only an appreciation of the self, but also of the human condition. It is evident in psychologist, spiritual leaders, and philosophers. These young adults may be shy but aware of their own feelings and are self-motivated.

Linguistic Intelligence: the ability to use language to express complex meanings. Linguistic intelligence allows us to understand the order and meaning of words and to reflect on our use of language. It’s the most widely shared human competence and is evident in poets, novelists, journalists, and effective public speakers. Young adults with this kind of intelligence enjoy writing, reading, telling stories or doing crossword puzzles.

Logical-Mathematical Intelligence: the ability to calculate, consider propositions and hypotheses, and carry out complete mathematical operations. It enables us to perceive relationships and connections and to use abstract, symbolic thought and sequential reasoning skills. This intelligence is important for mathematicians, scientists, and detectives. Young adults with logical intelligence are interested in patterns, categories, arithmetic problems, strategy games and experiments.

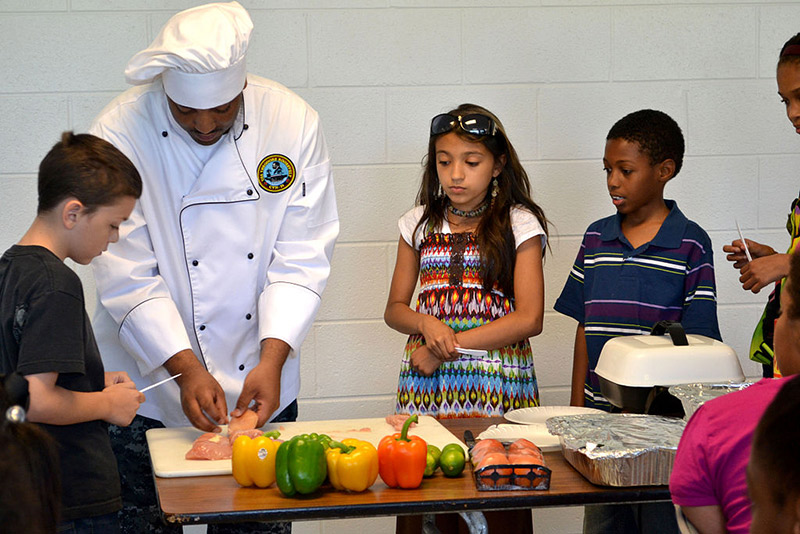

Naturalist Intelligence: the ability to discriminate among living things as well as sensitivity to other features of the natural world. This ability lends itself to botanists and chefs,but is also speculated that much of our consumer society exploits the naturalist intelligences.

Existential Intelligence: the ninth and final intelligence (not pictured in the chart above) regards sensitivity and capacity to tackle deep questions about human existence, such as the meaning of life, why do we die, and how did we get here. This intelligence also concerns cultures and religions. This intelligence might be attributed to philosophers, theologians and life coaches.” (6-7)

Multiple intelligence theory asserts that individuals possess “the full range of intelligences” but no two people share the same “intellectual profile,” or mix of skills in each category, which is shaped by both genetics and life experience.

Furthermore, possession of an intelligence does not guarantee its use. In fact, thanks to uniform testing and curriculums, some individuals may never discover their intellectual strengths – which makes incorporating Multiple Intelligence Theory into the classroom all the more important.

The Secret Spice

Inherently positive and empowering, multiple intelligence theory believes all students can succeed. Instead of molding students to a curriculum or test, the theory encourages students to explore, learn about themselves and take advantage of their individual strengths, talents and interests.

By incorporating the theory into lessons, educators acknowledge and activate intelligences, providing students with opportunities to discover their own strengths and talents.

Once students recognize their strengths and weaknesses, they can take responsibility in their own learning – taking advantage of their strengths while improving weaknesses. The first taste of success gives lifelong “failures” invaluable and refreshing confidence, leading to increased motivation and (in theory) more success.

Although multiple intelligence theory benefits students, it also makes teacher’s lives easier, acting as a simple, convenient tool for adding variety to a lesson. And I find it especially useful in the English classroom as an ALT in Japan. With so much to gain, educators should call upon the nine intelligences whenever necessary!

And there’s no situation more necessary than lesson planning. Dull lessons act as classroom kryptonite, stripping students of their will to learn, sucking away everyone’s energy, and destroying any chance of a positive atmosphere. Multiple intelligence theory became my secret spice, the flavor that added extra zing to my lesson plans. Whether applied to lessons created from scratch or those based on a textbook, Gardner’s theory always helps to mix things up.

Classroom Examples

During my time as a high school teacher I taped a list of the nine intelligences to my desk. Always a glance away, they became impossible to forget. When my mind went blank I knew where to look. Like the magic eight-ball, the list held an answer.

At times a lesson topic and intelligence would mesh perfectly. Other times combining intelligences and topics would be a fun, creative challenge. Creating warm-ups and activities to go along with textbook topics had been difficult, but The Nine Intelligences changed that. Here are some examples.

The musical intelligence sparked the use of Bill Haley’s song Rock Around the Clock to introduce time – afterwards students had no trouble remembering the term o’clock.

In honor of Halloween, the naturalist intelligence inspired pumpkin carving which also sparked the visual-spatial thinkers’ artistic abilities. Students reviewed face words and experienced another culture first hand. A week later we displayed their work at the school culture festival.

The body-kinesthetic intelligence made boring activities into fun games by adding movement. In one case, student pairs had match questions and answers. To make the activity more interesting I posted the sentences on the classroom walls. Students walked around the classroom, reading and remembering the questions and answers. Back at their desks they wrote down and then matched the questions with the corresponding answers.

In reading class I simplified a fable’s dialogue and students activated linguistic and body-kinesthetic intelligences by performing the story in the classroom. The performance assured they understood the story’s content, something that was later proven when they took a test on the unit.

I incorporated existential intelligence into a cultural lesson about the Amish societies of the United States. Students not only contemplated different religious beliefs but the reasoning, challenges and consequences of lifestyle choices.

In elementary school I incorporated the logical-mathematical intelligence into a dice game. Two students faced off, each casting a giant die. The first to add up the rolled numbers and say the answer in English would earn the team a point.

In kindergarten we played a game that activated interpersonal intelligence. First we chose a category. In this case, we chose fruit. Next, with students unable to see my paper, I wrote down four types of fruit in English. Student teams then chose four fruit, hoping to match my choices. Each correct match earned one point. Students not only considered what choices I would make (“Sensei said he likes strawberries, maybe he’ll choose that!”), but had to cooperate with group members when making their choices.

As time passed, incorporating different intelligences into lessons became natural. Variety within a single lesson is just as important as variety between separate lesson plans. I added opportunities for music, art and movement – venues for learning I had neglected. I started integrating multiple intelligences, using one for a warm-up activity, a different one for main activity and then another for the conclusion.

The lessons surprised students with their variety and originality. The lessons surprised me because they worked. Multiple intelligence theory became my secret spice – the heroes that made adding that variety to lessons (almost) as simple as glancing at a list.

Value In The Face of Criticism

Every hero team has an adversary or rival. In the nine intelligence’s case, it’s The General Intelligence Factor or Spearman’s g. Dating back to the early 1900’s, Charles Spearman sought a universal way to measure intelligence. His studies eventually spawned IQ tests which sowed the seeds of standardized testing and unified curriculums. Spearman concluded that with proper testing, anyone’s intelligence, regardless of strengths and weaknesses, could be determined and assigned an accurate value, called “g” (Brand and Kane).

Proponents of Spearman’s theory point out that multiple intelligence theory is not research based and therefore doesn’t produce quantifiable hard data (Armstrong 194). Its effectiveness is difficult to gauge.

Other claim multiple intelligence theory “dumbs down curriculum.” According to these critics, lessons incorporating music, art, and hands-on activities don’t produce solid, measurable results and thus have no place in a serious curriculum. Furthermore, these lessons pose the danger of giving students a false sense of accomplishment, making students feel smart and capable – even if they are not. (Armstrong 194)

Spearman’s g and Gardner’s multiple intelligence theory seem to oppose one another. But that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Competition between the theories will (hopefully) lead to improvements in education.

Yet, incorporating multiple intelligence theory into lessons doesn’t need to undermine the goals of standardized testing and curriculums. As my examples show, educators can incorporate the nine intelligences into a standard curriculum. The two theories can coexist.

Nine Intelligences! Assemble!

Whatever the case, multiple intelligence theory has too many benefits to ignore. To argue over a lack of hard data is to miss the theory’s point – education needs to address its learners’ diversity.

For me the theory became a useful, convenient tool for adding diversity to lessons. But the nine intelligences, my secret spices, those lesson-saving heroes add up to more than just a convenient “trick.”

As an English teacher it pleases me to see students do well on tests. But engineering lessons that awaken students that “hate,” “don’t understand” or “have no need for” English provides the most satisfying experience of all.

By harnessing the nine intelligences, I’ve been able to reach the unreachable, inspire the uninspired, motivate the unmotivated, and English the “unEnglishable” (is that a flash of linguistic intelligence there or a lack thereof?). For students that have never tasted success, that have never been given the opportunity to discover or use their talents in the classroom, sometimes a little variety is all it takes.