When I say Japanese food, the first thing you think of is probably sushi. And the second thing? These days, it's likely to be ramen. Everyone's familiar with the ubiquitous instant kind, and the real thing – stock simmered for hours, hand-made noodles, regional variations – is catching on in the US and becoming a foodie obsession. But ramen hasn't always been so central to Japanese cuisine, as I found when I read a fascinating recent book.

The Untold History of Ramen: How Political Crisis in Japan Spawned a Global Food Craze, by George Solt, is written by a serious academic historian (who confesses to preferring soba, despite having clearly spent a crazy amount of time thinking about ramen) and published by an academic press. What's a college professor doing writing about noodles? Well, it turns out that the story of ramen is a tale of Japanese history and culture in ways I could never have imagined. Let me take you on a tour of some of the highlights, and perhaps you'll be tempted to delve into the entire book as well.

The Birth Of Ramen

Ramen is complicated, and its history is messy.

Although ramen is now an iconic Japanese dish, it's actually an immigrant, and the names originally used for it made that perfectly clear. Chūka soba and Shina soba both basically mean "Chinese noodles" but have very different connotations. Chūka soba became the most-used term after World War II and is having something of a revival. It replaced shina soba as the political connotations of "shina" became controversial, since it was the word used for China when Japan was an imperialist power in Asia. But there's no dish in China that closely resembles today's Japanese ramen, so the story is much more complicated than a simple borrowing.

Solt presents three main origin myths about ramen, and what he calls "The first and most imaginative" comes from a book published in 1987. It credits a legendary feudal lord, Tokugawa Mitsukuni, as the first to eat ramen in the 1660s. This is based on a historical record of a Chinese refugee giving him advice on what to add to his udon soup to make it tastier, including garlic, green onions, and ginger.

It's unclear, to say the least, how much the modified udon soup resembled modern ramen, and in any case there's no direct historical connection – no one can argue that that soup gradually developed into the dish eaten today. However, the Ramen Museum of Yokohama popularized this story, and Solt attributes its appeal to the fact that it places the origin of ramen far back in Japanese history at a time when – as we'll see later – ramen is acquiring its modern symbolism as a quintessentially Japanese food.

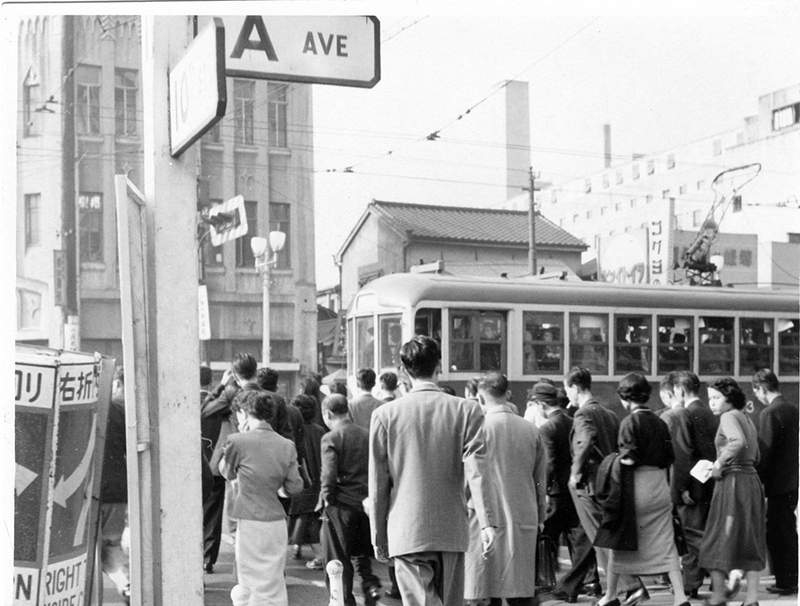

The second and more plausible story associates ramen with the opening of Japan to the outside world in the late nineteenth century. Port cities like Yokohama and Kobe attracted Chinese as well as westerners, who brought with them a noodle soup called laa-mien, handmade noodles in a light chicken broth. Japanese called the dish Nankin soba (Nanjing noodles) after the capitol of China. This soup didn't have toppings and was eaten at the end of the meal instead of being a meal in itself, so again, it's hardly identical to the ramen of today. But it does seem to have a far more legit claim to being a predecessor: the Yokohama version inspired Tokyo pushcart peddlers who started selling noodle soup in the old Ueno and Asakusa neighborhoods of Tokyo in the early twentieth century.

The third tale is similar to the second, but attributes the invention to a single person, which always makes a more satisfying story. In 1910, a shop called Rai-Rai Ken opened in the Asakusa district of Tokyo. The owner, Ozaki Kenichi, had been a customs agent in Yokohama, but the soup he served wasn't the unadorned nineteenth century version: it sounds like it would be familiar to anyone who's eaten ramen lately:

Rai-Rai Ken incorporated a soy sauce–based seasoning sauce and served its noodle soup, referred to as Shina soba, with chāshū (roasted pork), naruto (fish-meal cake), boiled spinach, and nori seaweed—ingredients that together would form the model for authentic Tokyo-style ramen.

The Young Adulthood Of Ramen

Solt argues that it wasn't enough to invent a recipe – the product had to have a customer base, basically, and in the late 19th and early 20th century, it was the right food at the right time, as Japan was becoming more industrialized and urbanized. Instead of living in rural areas where they grew and prepared their own food, more and more people had jobs in the cities and made money to eat in restaurants. Ramen wasn't a hand-made artisinal delight in those days – the attraction was largely speed and calories:

When making Shina soba, cooks prepared a pot of soup base and a bowl of flavoring sauce to serve an entire day's worth of customers, leaving only the boiling of the noodles and reconstituting of the soup to be left for when the orders were placed.

The short amount of time necessary to prepare and consume the noodle soup, and its heartiness compared to Japanese soba (which did not include meat in the broth or as a topping), also fit the dietary needs and lifestyles of urban Japanese workers in the 1920s and 1930s.

Ramen was also one of the first industrialized foods – a mechanical noodle-making machine was in general use by the late 1910s. At this point it was definitely still seen as foreign – it was largely eaten in cafes (kissaten) and Western-style eateries, as well as Chinese restaurants and street stands – and this was a point in its favor. Foreign food was regarded as more healthful and nourishing than traditional Japanese food, a theme that we'll see recurring later on, because it had more meat, wheat, oils, and fats.

That sounds crazy to us now, but remember that for most of history, people have had to worry less about being fat and more about starving to death. For workers who'd moved to the city from rural areas where they had to scrape as many calories as they could from the earth with their own two hands, the idea no doubt made perfect sense. So this period of ramen's history is intimately tied up with Japan's starting to develop into a modern, urbanized, industrial nation, turning away in some senses from its traditional past:

As Japan became industrialized and more urbanized in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Chinese restaurants and movie theaters gradually replaced the buckwheat noodle (soba) stands and comical storytelling (rakugo) performances that had previously dominated the cityscape. In this manner, ramen production and consumption became an integral component of modern urban life.

The Dark Days

In the 1940s, the war changed everything. At first ramen essentially disappeared, a victim of rationing and of the idea that this was no time for frivolous luxuries like eating out. Food shortages persisted after the war ended in 1945, and Solt says that the years between between 1944 and 1947 were the worst period of hunger in Japan's modern history. He quotes a scholar of Japanese food born in 1937 writing of his memories of that period:

From 1944 on, even in the countryside, the athletic grounds of local schools were converted into sweet potato fields. And we ate every part of the sweet potato plant, from the leaf to the tip of the root. We also ate every part of the kabocha we grew, including the seeds and skin. For protein, we ate beetles, beetle larvae, and other insects that we found at the roots of the plants we picked, which we roasted or mashed. Even in the countryside, food was scarce.

After the war ended, thousands of black markets including food stands sprang up, despite being technically illegal (the US occupation authorities continued both food rationing and a ban on outdoor food sellers). Because rice was hard to come by and wheat was being imported from the US, many foods based on wheat were popular – ramen, as well as yakisoba, gyōza, and okonomiyaki. Also heavy with garlic and oil, these were referred to as "stamina" foods, a term still in use today.

The dependence on U.S.-imported wheat flour as a substitute for rice during and after the American occupation set the stage for a couple of changes. One was that a generation grew up eating foods like bread, with the result that these are now a standard part of the Japanese diet. The other is that ramen took on an almost mythic status as the food that nourished people in a time of great hunger and despair.

Solt says that nowadays in retrospect that memory contributes to ramen's positive image, but at the actual time people felt rather differently. Popular culture such as radio and film used ramen as a symbol of the still-desperate times – an indication that a character can't afford to eat anything more expensive – and to highlight class differences and the growing generation gap in dining habits, since for older people the association with hearty food for laborers still clung to the dish. Here's one example from a movie Bangiku (Late chrysanthemums), released in 1954.

One of the four main characters is a single mother who must part with her only daughter, who is soon to be married and move away with her new husband. In one of the central scenes of the film, the daughter decides to treat her mother to a meal before she leaves, taking her to a Chinese eatery. The mother, though appreciative, reminds her daughter that this is the first time the daughter has treated her to a meal. As the two silently eat Chūka soba together, the daughter's marked enthusiasm for the dish and the mother's disdain symbolize the vastness of the generation gap. The scene makes it evident that to a middle-aged mother from a middle-class background in Japan at the time, ramen still could not be eaten without a sense of embarrassment.

The Boom Years

As Japan's economy boomed in the period from 1955–73, ramen boomed too. Tokyo in the early 1960s was building venues for the 1964 Olympics as well as development inspired by it, including major transportation projects like new subways, the shinkansen, and five new expressways. Vast construction projects required vast numbers of construction workers who ate vast numbers of bowls of ramen, and it also became a staple for students and young people who had grown up eating more wheat and meat.

In this period of rapid social change there's way too much going on to cover in a short article (there's a reason why Solt had to write a whole book) including the invention and popularization of instant ramen, a subject that will definitely have to wait for a post on its own.

But one thing I can't leave out that I found quite surprising was the continuing development of the idea that Western foods – including wheat in particular – were healthier. The Ministry of Health and Welfare actively promoted this idea and nutrition scientists happily jumped on the bandwagon. Some of this promotion and "science" took the rather odd form of attributing cultural differences and Western superiority – which apparently went without saying – to the difference in diet. Here's one authority's argument:

The character [seikaku] of rice-eating peoples and the character of wheat-eating peoples are naturally different , where the former believe that people eat because they exist, while the latter believe that people exist because they eat. Each of these are the result of the types of food that they eat, and while the former are resigned and passive, the latter are progressive and active. . . . [Because of the tasty and satisfying nature of rice,] peoples who eat rice easily become accustomed to that way of living, and they lose their will to be active. . . . [People who consume wheat ] find that it alone does not taste good, which makes them desire more than what they already have, motivating them to become active and providing the initiative for them to achieve progress, and the result is that they move in the direction of wanting other types of foods… The need to turn the wheat into wheat flour and then to combine it with other foods such as meat and dairy products has led to many innovations that together have produced the wheat-flour based food culture of today. . . . The relative ease of the rice-based dietary lifestyle naturally leads people to move away from things such as reason [wake], thought [shikō], and contrivance [kōan]. Scientific experimentation and development do not advance in such a context.

That passage is laughable today, but others verge on shocking. Here's another nutritionist:

Parents who feed their children solely white rice are dooming them to a life of idiocy. . . . When one eats rice, one's brain gets worse. When one compares Japanese to Westerners, one finds that the former has an approximately twenty percent weaker mind than the latter. This is evident from the fact that few Japanese have received the Nobel Prize. . . . Japan ought to completely abolish its rice paddies and aim for a full bread diet.

This author's work became the basis of a pamphlet by wheat producers who, not mincing any words, used the title "Eating Rice Makes You Stupid."

Ramen Against The Man

While the government and scientists were pushing a wheat-based diet, ramen in particular was still associated with poverty and struggle in popular culture, but things were beginning to change. With more money around to be spent, ramen developed from a cheap pushcart product into something you ate at a moderately priced restaurant. And at the same time that instant ramen – the most industrialized food possible – was becoming popular, we see what could be considered the first hints of the modern hand-crafted ramen movement. In the 1970s, something that was all the rage – at least according to the media at the time – was the datsu-sara, "salaryman escapee." These were men who left successful careers to become self-employed – farmers, say, or ramen cooks.

As someone who has written for newspapers, I can tell you that the general rule is that you only need to find three of something for an editor to call it a trend. But one newspaper even ran a weekly "Datsu-sara Report," so if they could find enough material for that, maybe it really was a Thing. In any case, in this context, running a ramen shop was seen as the kind of work that provided a degree of independence and creativity that wasn't possible in a corporate environment. This romanticization of the ramen maker is the start of an entirely new symbolism around ramen.

Ramen Becomes Trendy

In the 1980s, ramen started to become almost as much a fashion item as a food. The traditional pushcarts were disappearing and the Chinese restaurants and diners that used to sell it were declining, replaced by the specialty ramen shop with a more limited menu and a higher price. The manual workers who were its old customer base were also fewer in number, and now the stereotypical ramen eater started to be the young urban consumer who was labelled with the term Shinjinrui, "new breed."

Rather than fuel for hard physical work, for many ramen starts to become basically a hobby. The phenomenon of waiting in line for hours at a special ramen shop became common enough that people who did it were given a name, "rāmen gyōretsu." The 80s also saw the start of the obsession with special regional varieties of ramen and fans who would travel to far-away places especially to taste a new kind they'd read about. And by the 1990s, he says:

Ramen chefs were appearing on television, writing philosophical treatises, and achieving celebrity status in Japanese popular culture, while their fans were building museums and Internet forums.

Ramen Turns Japanese

Given its birth as a foreign import, and the central role that foreign wheat plays in the dish, it's odd that ramen would become a symbol of traditional Japan, but that's exactly what happened. The new customers had been born after the period of war and post-war hardship, so its older associations were purely nostalgic – a comfort food that seemed native in contrast to elegant European gourmet cuisine. Shops stopped having names and decor with Chinese associations – no more red and white noren – and the chefs began to dress differently:

In the late 1990s and 2000s, however, younger ramen chefs, inspired primarily by Kawahara Shigemi, founder of the ramen shop Ippūdō, started to wear Japanese Buddhist work clothing, known as samue. Usually worn by Japanese potters and other practitioners of traditional arts, the samue, usually in purple or black, was worn by craftsmen in eighteenth-century Japan… The new clothing suggested that the ramen maker was now considered a Japanese craftsman with a Zen Buddhist sensibility rather than a Chinese food chef.

And now, instead of western food being argued to produce superior people, apparently some started using ramen to argue it was the other way around, to the extent that it caused a backlash in some quarters: one newspaper article headlined a section on the ramen boom, "The Frightening Situation Where Plain Old Ramen Becomes the Basis for 'Theories of Japanese Superiority."

And this brings us to where we are today, where ramen shops are now appearing in fashionable cities all over the world, presenting what's seen as a quintessentially Japanese dish:

[Ramen] has gained a reputation as a relatively affordable, youthful, and fashionable representation of Japanese food culture, unlike sushi, which has very different symbolic baggage. Ramen is now an important component of both official and unofficial attempts at remaking "Japan" as a consumer brand for foreigners.

The artisanal hand-made type of ramen and its cultural baggage fits perfectly into modern culinary obsessions – an earthy, authentic, hand-made comfort food. And at the same time, instant ramen has taken over the world even more – did you know that Mexicans buy one billion servings annually? But if you want to know more about that, you'll have to read the book yourself.