Dear readers, I don’t mean to alarm you, but we are currently experiencing an alien invasion. Some of these aliens are just arriving, but others have been amongst us for decades. They have contaminated our seas, our wilderness, our gardens, and even our food. But these aliens are not from another world. No, I speak of invasive species from right here on our own little blue-green marble. These are species that have been introduced to environments to which they are not native, and may cause significant damage. Some of these species are native to Japan, and they are absolutely fascinating.

Japanese Beetles

“Oh what a pretty beetle,” you might be thinking. Its carapace has such lovely iridescent green and copper colors. There’s another one. And another. Now they are everywhere. “What are they doing to my hydrangeas? Have mercy, not the hydrangeas!”

You, like so many suburbanites, have fallen victim to Popillia japonica, the Japanese beetle. In Japan they are known as mamekogane 豆黄金, or “mini-gold.” The mamekogane menace has spread to China, Russia, Portugal, Canada, and the United States. It was first discovered in the U.S. in New Jersey in 1916. It’s thought that they were introduced as larva in a shipment of imported iris bulbs prior to 1912, when inspections for such things began. In the intervening decades they have spread to over thirty states.

A pest through much of its one year life cycle, after hatching the grub eats grass roots, potentially killing lawns in their subterranean assault. They emerge as adults around July to wreak havoc on a new front. Japanese beetles are known to consume the leaves of over 300 different species of plants, chewing around the veins of a leaf, so that only a skeleton remains. On average the beetles live as adults for about 60 days, during which time they feed, mate, and lay their eggs. Over those two months, a single female can lay up to 60 eggs, and thus the cycle begins anew.

How can we battle the beetle? American homeowners often resort to an arsenal of poisons and traps, but I’ve often wondered what keeps them under control in their homeland. The English sources I’ve seen sometimes state that they have natural predators which are not present in the territories they have invaded, but don’t offer much on what those predators might be. According to Japanese sources, as larva, Japanese beetles are preyed upon by the likes of crows, moles, centipedes, and ants. As adults they are hunted by birds, robber flies, and some wasps of the Scoliidae family. Of course, most of these animals are present in much of the territory the beetle has invaded, so I’m not quite sure where the difference lies and why their reign of terror continues.

Kudzu

It is coming. Inexorably it extends its tendrils, creeping over trees, walls, abandoned cars and homes until it engulfs everything in a leafy sea of green. It is coming.

Kudzu refers to several vines in the genus, Pueraria. The name comes from the Japanese word for the plant, kuzu. Kudzu was introduced to the U.S. in 1876 at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and to the Southeast region in 1883 at the New Orleans Exposition, but it wasn’t clear from my sources if they really knew what they were dealing with. Kudzu’s high growth rate must have soon become apparent, but for decades this quality was seen as an advantage. In the first half of the twentieth century, it was used as both cattle feed and as an erosion-preventing cover plant. It was not until 1953 that the U.S. Department of Agriculture removed kudzu from its list of suggested cover plants, and in 1970 they finally listed it as a weed. It was too little, too late.

Kudzu became known as “the vine that ate the South,” where it’s now estimated to cover over 3,000,000 hectares (7,400,000 acres) of land. Under ideal conditions (like those in the American South) kudzu can grow up to a foot a day! It can smother other plants, making it a threat to biodiversity. It’s also incredibly resilient. It’s even resistant to herbicides. Physically removing it is like fighting the hydra, as it requires removing the crown of the plant as well as removing and burning all the vines, lest they take root again.

Various bugs and fungi are being tested as ways of fighting kudzu, but a perfect solution has yet to be found. The fungal pathogen, myrothecium verrucaria seems like it could be quite effective, but has the unfortunate downside of being highly toxic to mammals. The best method may actually be to let goats or sheep graze on kudzu, as even a small herd can clear an acre a day. Of course, that may not be a feasible solution in every situation.

At least Kudzu can be used for some practical purposes. The stems can be used to weave baskets. Its fibers can be used to make paper or cloth. The starchy roots can be used to make a powder used in Japan for making food like kuzumochi, kuzumanju, and kuzukiri, or in hot water as kuzuyu.

Japanese Knotweed

There is another herbaceous horror from Japan that is now plaguing poleis across the U.S., U.K., and New Zealand. Like kudzu, Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) is a fast grower, and has a strong root system, allowing it to damage roads, concrete foundations, and other manmade structures.

Despite its English name, Japanese knotweed is also native to China and Korea. In Japan it is most commonly known as itadori, but has other names in various dialects. Japanese knotweed has become so problematic in the U.K. that some banks and mortgage companies have refused mortgage applications due to knotweed having been found on the property, or even the neighboring property.

Controlling Japanese knotweed is quite difficult, because to kill the plant one must eliminate the entire large root network. These roots can grow up to three meters (ten feet) deep, and leaving only a small amount can be enough for it to quickly regrow. Various control methods have been tried, including herbicides, digging up the roots, covering the plants with concrete slabs, and injecting steam into the affected soil, but none of these have been foolproof. In Japan, a certain leafspot fungus is particularly potent against knotweed, and foreign research on it is being carried out. There has also been an experimental attempt to introduce psyllid insects into the wild in the U.K.. Their diet is exclusively knotweed and the attempt showed potential. Let us hope it is not too late.

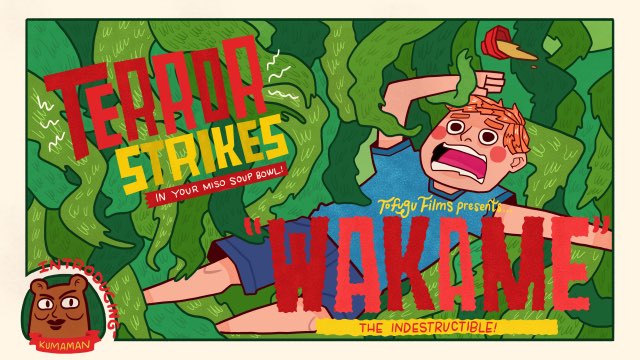

Wakame

Look! There! It’s something green and slimy. What’s that lurking in the depths of your miso soup? The algae known as wakame may seem innocent enough, but this sinister seaweed has been carrying out a naval campaign for over thirty years.

Native to the coasts of Japan, Korea, and China, wakame is a species of brown kelp, known to scientists as Undaria pinnatifida. Like other seaweeds, wakame has no roots, drawing its nutrients from the water. However, it does have root-like appendages that allow it to attach itself to rocks, shellfish, pilings, buoys, anchor chains, and other surfaces. Wakame can also survive in a relatively wide range of temperatures and salinities, aiding in its invasion of new territories.

It is thought that it was most likely introduced to new areas by attaching itself to ships or finding its way into their ballast water. Once it enters a new environment it can spread quickly, scattered by the currents, clinging to new surfaces, and reproducing via microscopic spores. Wakame’s full impact on an alien environment is not well understood. Full grown wakame forms dense forests which reduces the light and slows the water in their territory.

Wakame has been found in Australia, New Zealand, Italy, Mexico, and Argentina. After being introduced to Brittany as a crop in 1983 it spread to the UK, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Spain. It is also present on the west coast of the U.S. It has become a bit of a problem in San Francisco Bay, where it was first found in 2000. There have been efforts to keep it under control by people such as Dr. Chela Zabin, a biologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Dr. Zabin recalled her reaction after first encountering wakame in the bay: “Oh God, this is it, it’s here. I was really hoping I was wrong.”

Tsunami Invaders

The latest front in the struggle against invasive species is on the west coast of North America. The 2011 tsunami caused much death and devastation in Japan, but its aftereffects are also being felt elsewhere. The currents have eventually brought both debris and new species across the Pacific to North America. The aforementioned wakame has been brought to new territories, as have the Northern Pacific seastar, Asian shore crab, Mediterranean blue mussel, and others. There are estimates that tsunami debris could continue to wash up on North America for up to ten years. Authorities are largely relying on citizens to report the arrival of debris, so if you are a resident of the West coast remain vigilant. You never know when a new invasive species may rise from the depths. Stay alert, my friends.