Even in situations when Japanese people are quite positive that something is true, they typically hold back on expressing claims. Similar to how one might use a layer of wrapping paper to hide what is really within a package, when speaking Japanese, Japanese speakers regularly encase their assertions in language that implies they aren't sure about it. To suit this social tradition, Japanese offers a variety of grammatical terms for different degrees of certainty.

For example, consider a scenario where you arrive at work in the morning, and a coworker asks you whether you left a document on her desk last night. You did not do that, but you believe another coworker, Tanaka-san, may have. This is what you can say:

- 田中さん[かな / かも / な気がする / だと思う]。

- It might be Tanaka-san.

These four terms are presented in order of degree of certainty: from least certain to most certain. Although four might seem like enough, that's merely the tip of the iceberg. Japanese has a lot more similar expressions, and understanding them is crucial for speaking the language in a more Japanese-like manner.

To assist you in using Japanese in a way that possibly sounds more Japanese, this article discusses those terms in order of degree of certainty. Are you ready to learn them? Maybe? Perhaps? Well, it seems you are ready, I suppose. So, let's get the ball rolling!

- A Big Picture Look at Degree of Certainty Words

- Expressions For Conveying a Low Level of Certainty

- Expressions For Conveying a Medium Level of Certainty

- Expressions For Conveying a High Level of Certainty

- Adverbs For Different Levels of Uncertainty

- Quite Possibly the Conclusion

Prerequisites: This article assumes you already know hiragana and katakana. If you need to brush up, have a look at our Ultimate Hiragana Guide and Ultimate Katakana Guide.

Notes: This article concentrates more on the subtleties of each term, particularly in ordinary speaking or writing. Some expressions might not be appropriate in formal writing, such as academic writing, as formal writing tends to require a rigid and assertive style in general.

A Big Picture Look at Degree of Certainty Words

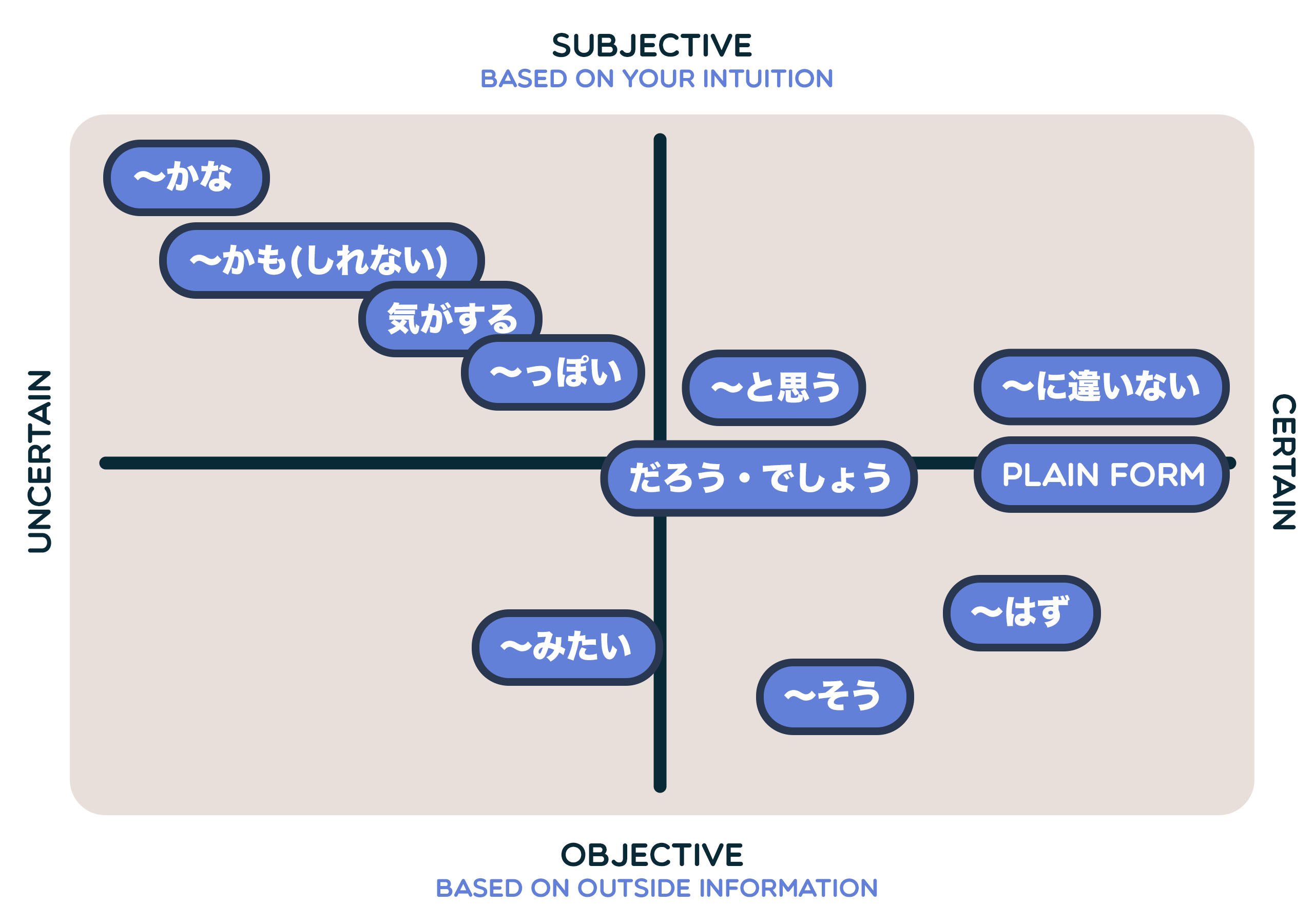

As mentioned in the introduction, there are plenty of ways to convey your assumptions in Japanese. All of these expressions are for "judgments" made in light of the available information. The certainty of the judgment, however, can be different depending on how much information the speaker knows, and how much they rely on it to make judgments, as well as whether or not they reached their assumption subjectively or objectively.

To help your understanding, here's a chart to show you a rough idea of the certainty level and how subjectivity or objectivity each term sounds:

"Certain" and "uncertain" should be pretty self-explanatory, but what do I mean by "subjective" or "objective"? Basically, the more "subjective" a term is, the more heavily it's based on your own assumptions and intuition, whereas more "objective" terms rely a bit more on outside information or past experiences in conjunction with your own thoughts.

Don't worry if you aren't familiar with these exact expressions yet, though — we're going to go over them one by one. Also, if you feel like this table is missing some other words you already know, such as 多分 (perhaps) or きっと (surely), rest assured that I'll be covering them in this article as well, but in a separate section at the bottom!

Expressions For Conveying a Low Level of Certainty

To start, let's introduce expressions for conveying the lowest level of certainty.

〜かな for "I Wonder…"

To express your feeling of uncertainty, you can use 〜かな. 〜かな is the equivalent of the English phrase "I wonder…" It's often used with a notion or a hypothetical scenario that has come to mind, and implies that you should take it with a pinch of salt.

For example, if you sneeze and you wonder if you have a cold, you can stick 〜かな onto 風邪 (cold) and say:

- 風邪かな。

- I wonder if I have a cold.

Here, 〜かな expresses that while you think you might have a cold, you are still unsure and are wondering about it. 1 2

You can also attach かな to a longer sentence. For instance, if you wonder you may develop a fever, you could say:

- 熱が出るかな。

- I wonder if I'm getting a fever.

In a way, 〜かな is sort of like asking yourself a question, and thus it's considered an informal expression.

Again, in this example, 〜かな indicates that even though you're afraid of getting a fever, you are still unsure and wondering about it.

Due to its nature, 〜かな lacks the polite form. 3 To express this sort of speculation when speaking to someone in a polite manner, you can instead use 〜ですかね or 〜ますかね, or the more formal 〜でしょうか(ね).

- 風邪[ですかね / でしょうか(ね)]。

- I wonder if I have a cold.

(Literally: Do you think I have a cold?)

- 熱[出ますかね / 出るでしょうか(ね)]。

- I wonder if I'm developing a fever.

(Literally: Do you think I will develop a fever?)

Here, です and ます are the marker for the politeness, か is the question particle, and ね is the confirmation-seeking particle. And, でしょう is one of the grammar points used to express speculation. If you aren't familiar with them, check out the linked pages!

〜かもしれない for "May" or "Might"

〜かもしれない is the Japanese equivalent of "may" or "might." It communicates the implication that something may be true, but you're not completely sure. In other words, it refers to your guess when there is no concrete proof to support it.

Let's use the same scenario of you sneezing. Instead of "you wonder," you think you might have a cold. In this case, you can use 〜かもしれない and say:

- 風邪かもしれない。

- I might have a cold.

Here, 〜かもしれない shows that even if you suspect that you might have a cold, you aren't so sure. If you're very certain that your sneeze is being caused by a cold, you shouldn't use 〜かもしれない.

Note that 〜かもしれない is often shortened to just 〜かも in casual conversation, or in self-directed speech. So if you now have some chills and are telling your family member that you might develop a fever, it's common to drop しれない and say:

- 熱が出るかも。

- I may develop a fever.

Although it is grammatically incorrect, some people use 〜かも with です to lend a sense of casual politeness. So if you're telling one of your superiors at work that you're friendly with that you might get a fever, you could say:

- 熱が出るかもです。

- I may develop a fever.

However, you would use the proper polite form, 〜かもしれません, if you were speaking to another senior employee with whom you have a stiff, square relationship.

- 熱が出るかもしれません。

- I may develop a fever.

Alright, you've probably had enough of 〜かもしれない expressions, so let's move onto the next expression!

〜気がする for "I Have A Feeling…"

〜気がする literally translates to "have a feeling," and it's used to express that you aren't certain but "you have a feeling that something might be the case."

Since 〜気がする indicates that you have a hunch about something, it sounds slightly more certain than 〜かな (I wonder) or 〜かもしれない (maybe/might). However, the certainty level of this expression is still low, because it only conveys a feeling or guess based on intuition, rather than known facts.

Let's reuse the sneezing example to see how it works. After a big achoo, if you intuitively think "Oh, I may have a cold," then you can use 〜気がする and say: 4 5

- 風邪引いた気がする。

- I have a feeling that I have a cold.

Here, 〜気がする expresses that while you get the feeling that you have a cold, there isn't any solid evidence to support this.

What if you've been experiencing chills and want to inform your boss that you sense a fever is coming next? In this circumstance, you can use the polite 〜気がします and say:

- 熱が出そうな気がします。

- I have a feeling that I may develop a fever.

Once more, 〜気がします demonstrates that while you do have a sneaking suspicion that you may get a fever, there isn't any concrete proof to back this up.

Alright, now that we've covered all the low certainty expressions (with the exception of adverbs, which we'll learn later), let's move on to the expressions for conveying a medium level of certainty!

Expressions For Conveying a Medium Level of Certainty

In this section, we'll discuss expressions that convey a medium level of certainty. You might use these when you think you have some evidence to support your argument, but it remains a matter of conjecture, and you don't want to assert thoughts too strongly.

〜っぽい for "Like…," "-ish," or "It Seems…"

〜っぽい is a slang-ish suffix that expresses similarity, as in "(feel) like…," or "-ish" in English. For example, if you feel like you have a cold, you can say:

- 風邪っぽい。

- I feel like that I have a cold.

And if you're feverish, and you want to report that to your boss, you can add the polite です and say:

- 熱っぽいです。

- I feel feverish.

In these examples, 〜っぽい casually indicates that you have some symptoms of a cold or fever, but you don't necessarily know if you have an actual cold or fever.

〜っぽい can also follow the situation in which you think it's likely true based on your observation, like:

- 風邪引いたっぽいです。

- It seems like I have a cold.

In this case, 〜っぽい adds a sense of ambiguity, like "Given the symptoms, it's likely I have a cold, but it's not a 100% sure thing."

〜みたい for "Like…" or "It Seems…"

Similar to 〜っぽい, 〜みたい is a suffix that expresses similarity or resemblance to something else. For instance, if you find a yellow tomato that tastes like or looks like a banana, you can say:

- バナナみたい。

- This is like a banana.

Depending on the situation, the use of 〜みたい here suggests that the yellow tomato has a flavor or appearance that is similar to a banana.

In case you're curious, 〜みたい and 〜っぽい are comparable but distinct terms. バナナみたい means that you think the tomato somehow resembles or is similar to a banana, while バナナっぽい describes the tomato as having characteristics that are kind of like a banana.

Now, let's switch 〜っぽい with 〜みたい in the earlier example 風邪引いたっぽい。(It seems like I have a cold.), as in:

- 風邪引いたみたいです。

- It seems like I have a cold.

〜みたい and 〜っぽい are indeed very similar, and have the same translation when used in this way. If I were to be picky, there are very small differences between the two, though.

That is, 〜みたい demonstrates your assessment that your condition is comparable to, if not the same as having a cold, whereas 〜っぽい shows that, given your current circumstance, you get a feeling that you have a cold.

Since 〜みたい indicates your assessment, 風邪引いたみたいです is slightly more certain than 風邪引いたっぽいです. However, due to the ambivalence added by 〜みたい, 風邪引いたみたいです still presents the message that you're aware that you probably have a cold, but are coming to terms with it.

〜だろう/〜でしょう for "I Guess Probably…"

If your hypothesis about something is based on opinions and perspectives with some justifications, you can use the expression 〜だろう, or its polite form 〜でしょう, as in:

- 風邪だろうね。

- I guess that's probably a cold.

- 熱も出るでしょうね。

- I guess that they'll probably develop a fever, too.

Here, 〜だろう/でしょう suggests that you are making a personal guess that you believe is probably true, while also suggesting that it is supported by some form of evidence.

These terms are typically used while making an observation and drawing your own conclusions. Although it is possible to use them to talk about yourself, talking about somebody or something else is far more typical.

Another thing to keep in mind is that だろう, or its abbreviation だろ, has an unrefined and rugged tone as-is. This rough-hewn aspect works well when you're making an affirmative statement about your guess in writing or in a formal speech. In ordinary speaking, however, it sounds tough and is often considered masculine.

To soften the sound, the final particle ね is commonly used with it, just as in the examples above 〜だろうね. On the other hand, 〜でしょう is a very polite expression and is favored in formal situations. Adding ね to it, as in 〜でしょうね, can make it sound feminine, though it's used across the gender spectrum in formal settings.

For these nuances, both 〜だろう and 〜でしょう might not always be the preferred choices in ordinary conversations. Instead, many people choose 〜と思う (I think…) instead to convey their assertion in general situations. Speaking of which, you can just scroll down to see how 〜と思う is used!

〜と思う for "I Think/Believe…"

When you draw a conclusion based on some evidence, and actually believe it's likely to be true, you can use the expression 〜と思う (I think/believe…), which is the combination of the quotation marker と and the verb 思う (to think).

For example, if you not only sneezed but have chills and fatigue, you may say:

- 風邪引いたと思う。

- I think that I have a cold.

Here, 〜と思う expresses that you have some reason to back up your claim, and you naturally came to think that's probably the case.

When you say 〜と思う, you are merely expressing a thought, idea, or notion that just occurred to you.

If you're wondering why the word "naturally" was inserted there, good eye! Japanese has two verbs for "think," 思う and 考える. Between the two, 思う refers to more spontaneous thinking that bubbles up naturally "in your heart," while 考える is a more methodical kind of active thinking, which we might say happens "in your head." 6

Now, let's take a look at the above example 風邪引いたと思う again. Here, the claim 風邪引いた (I caught/have a cold) is a highly convinced sentence in and of itself (we'll talk about this later too!), and what 〜と思う is doing is actually softening the assertion by stating that it's the notion that naturally came to you.

For this reason, the certainty of 〜と思う changes depending on the sentence you attach it to. For example, you can decrease the level of certainty by adding 〜かな (I wonder) or 〜かも(しれない) (may/might) to the claim, like:

- 風邪引いた[かな / かも(しれない)]と思う。

- I think that I may have a cold.

In this case, 〜と思う softens the already vague かな/かもしれない statements and makes them even less certain. On the other hand, if you add an adverb like 絶対 (definitely), it becomes a strong conviction:

- 絶対風邪引いたと思う。

- I think that I definitely have a cold.

But again, just saying 絶対 風邪引いた without 〜と思う is stronger, and what 〜と思う is essentially softening the strong statement.

This happens in English too, but as was mentioned in the beginning, Japanese people typically reserve making assertions about something unless they are fully certain that it is accurate. As a result, you hear 〜と思う, or 〜気がする (I have a feeling…), used with many Japanese remarks to help the speaker feel at ease.

There was a lot in this section to take in, huh? One final point: the polite form of 思う is 思います. So, use 思います when telling your thoughts to someone with whom you need to speak to in a courteous manner.

〜そう for "It Looks/Seems Like…"

You can also use 〜そう when you believe that something is about to happen, someone is going to do something, or some condition might be the case. For example, if you feel like you might develop a fever, you can combine it with the verb 出る and say:

- 熱が出そう。

- It looks/seems like I'll develop a fever.

〜そう can also be used with adjectives, too. For example, if your friend noticed you weren't feeling well, they might add 〜そう to an い-adjective しんどい and say:

- しんどそうだね。

- It looks/seems like you're not feeling well.

As mentioned earlier, 〜そう basically translates to "it looks/seems like" in English. To put it another way, you can use this to simply describe what you think is going to happen, based on your observation of the present situation.

Since 〜そう is basically your report on what something "looks/seems like" based on your observation, its certainty level is slightly higher than other expressions we've learned so far. However, it still implies that you aren't certain, so when talking about what's seemingly about to happen, it often goes well with 〜気がする, as in:

- 熱が出そうな気がする。

- I have a feeling that I will seemingly develop a fever.

Note that since 〜そう is an expression that's dependent on what you are observing at the time you're speaking, you cannot use it to explain an event that happened in the past. 7

Expressions For Conveying a High Level of Certainty

Now you've learned all the expressions for low and medium certainty, let's move onto the high-certainty expressions.

〜はず for "Supposed To Be" or "Should Be"

If you think that something is "supposed" to be or "should" be the case, foreseeably based on objective, logical inference, the phrase 〜はず comes in play.

So if you have sneezed, get some chills, and foresee that a fever is about to develop, you can say:

- 熱が出るはず。

- I should have a fever soon.

Here, 〜はず indicates that you believe that it's highly likely that a fever is coming soon, and that belief is based on plausible information.

And if your assistant at work has some memory of having acetaminophen in the office cabinet, they could politely say:

- 薬があったはずです。

- There should be some medication, if I remember correctly.

In this example, 〜はず suggests that they have a memory of having some medicine, if their memory is accurate.

In other words, 〜はず indicates a great degree of certainty, but not 100%. It conveys that you assume or believe that something is the case, but that you're aware that it's not necessarily so.

〜に違いない for "Must"

Like 〜はず, 〜に 違いない also denotes a high degree of certainty, but it implies that your own subjective judgment is involved to reach the conclusion.

It's easier to grasp the nuance of 〜に 違いない while comparing it with 〜はず, so let's bring back the earlier example of you foreseeing an upcoming fever for comparison:

- 熱が出る[はず / に違いない]。

- I should have a fever soon.

The implication here is very similar, as both imply that you've reached the assumption that you are highly likely to have a fever soon, given that you currently have sneezes and chills.

〜に違いない sounds more confident and strong than

〜はず, because it conveys your personal conviction on the conclusion.

The literal meaning of 違いない is "no difference" or "not a mistake." It indicates that something is exactly what you think without any difference or inaccuracy.

Thus, the literal meaning of the word 〜に違いない is "I affirm that XYZ is accurate and correct in every aspect," which of course conveys a very high degree of certainty.

As you can see, what 〜に違いない implies is quite rigid. Hence, it's more of a literary expression than colloquial.

Although 〜はず and 〜に違いない were interchangeable in the above example, because of the slight difference in nuance, they can't always be swapped. For instance, due to its strong confidence, 〜に違いない cannot be used in the situation where you remember something and it's highly likely, but you aren't 100% sure, like:

- 薬があった[はず(です) / ❌に違いない(です) / ❌に違いありません]。

- There should be some medication, if I remember correctly.

If you use 〜に違いない, or its polite forms 〜に違いないです or 〜に違いありません, in the above sentence, it would sound as if you're a detective or a some sort investigator — it's as if you're drawing conclusions about the crime scene and asserting that some sort of medication must have been present at a specific location in the past.

The base of your claim can be either facts, knowledge, or even just your instinct, but with all the information at your disposal, 〜に違いない expresses that you cannot be certain that that will be the case.

For this connotation, detective characters in fiction may frequently employ 〜に違いない in speech. However, few people want to sound like detectives in real life, so to say the same thing, people typically use 〜と思う, or its polite 〜と思うんです or 〜と思います, with an adverb, such as 絶対 (definitely):

- 絶対薬があった[と思う / と思うんです / と思います]。

- I surely think that there was some medication.

We'll soon go through all the adverbs for varying levels of certainty. Before moving on, however, we have one last expression for high certainty to discuss: the plain form.

Plain Form for "Realization" or "Conviction"

The majority of textbooks don't mention this, but when Japanese people have just realized something or are finally convinced that something is the case, they typically just state it using the word in its most basic "plain form."

For example, if you sneeze and become convinced that you have a cold, you might simply use the plain form and say:

- あ、風邪引いた(わ/な)。

- Oh, I have/got a cold.

Then, if you feel a chill coming on and are certain a fever will start, you can say:

- うん、熱も出る(わ/な)。

- Yep, I'm gonna have a fever.

Now suppose you genuinely start feeling sick and have a high fever, and believe it's a flu. You might say:

- インフルエンザだ(わ/な)。

- This must be the flu.

These examples all have a plain form ending, either in the present or the past tense. They can still take sentence-final particles that are directed at yourself, such as わ (a judgment/sentiment marker) or な (a discovery marker). But even without them, ending a sentence in a plain form sufficiently communicates your judgment or your discovery that something is true and that you are confident in it.

You don't typically see the polite form in this use because it's essentially used for a self-directed realization or conviction. However, you may use the polite form if you are talking to the audience and speaking in a polite manner in general.

For instance, if you're live-streaming your life and you think you have a fever the moment you've sneezed, you could say:

- あ、風邪引きました(ね)。

- Oh, I have/got a cold.

Then, if you feel a chill and anticipate a fever coming on, you can say:

- うん、熱も出ます(ね)。

- Yep, I'm gonna have a fever.

And then, you actually get really sick and have become to think you have the flu, you could say:

- インフルエンザです(ね)。

- This must be the flu.

As you can see in the examples, it's customary to use the particle ね in this situation to solicit audience agreement, as in "do you agree with my realization?"

Okay, now that we've gone through every expression for certainty, all that's left is to look at adverbs! Don't be alarmed; since you've already learned so much, I'll only briefly go through each adverb. So, let's keep on and get to the finish line of this article together!

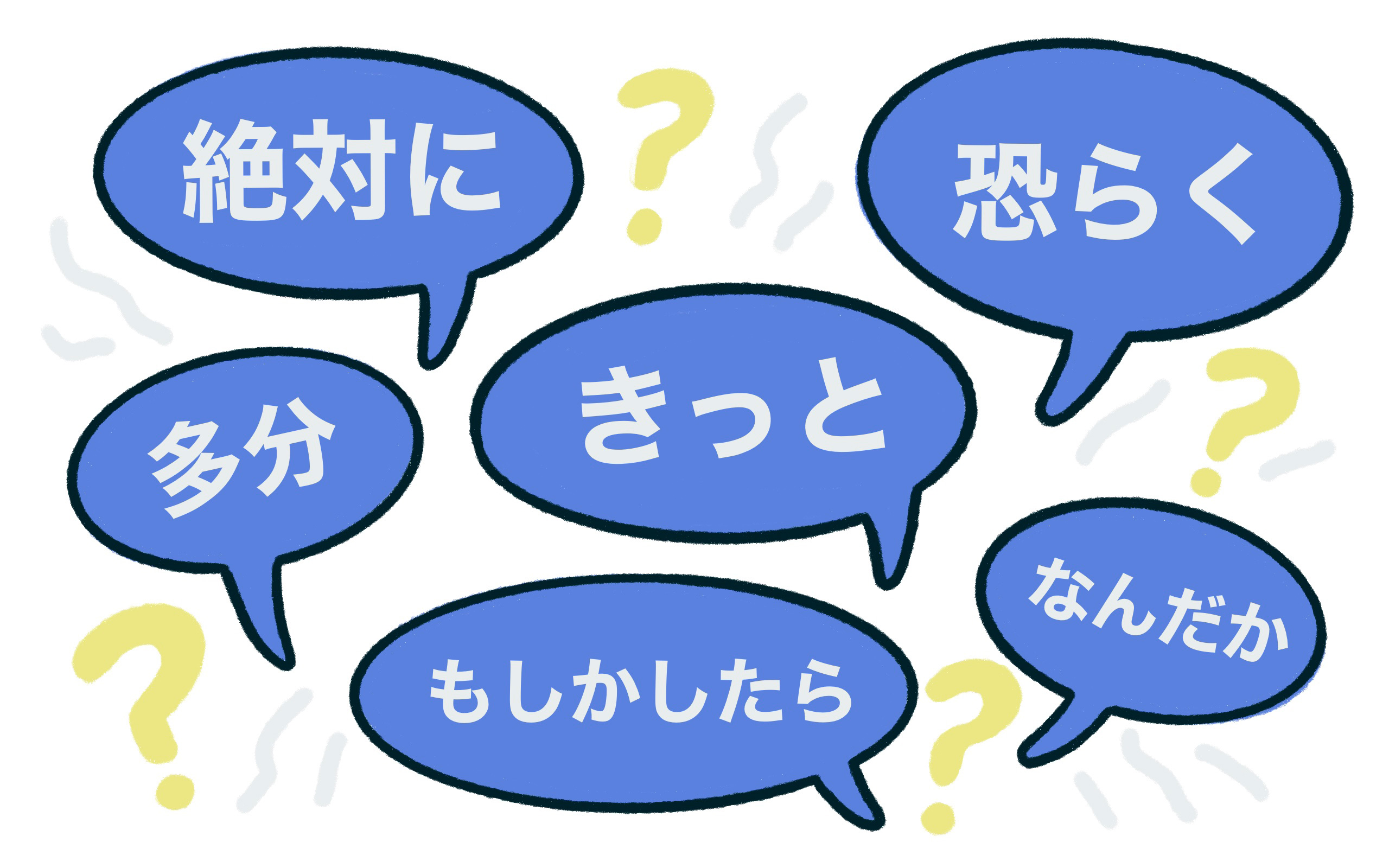

Adverbs For Different Levels of Uncertainty

In addition to the expressions learned above, there are adverbs that denote various degrees of uncertainty. These adverbs frequently go together with other expressions you previously learned, particularly with 思う, but the frequency of collocations depends on the word.

As promised, we won't go into great detail about each adverb in this part; instead, I'll list the basic adverbs for different levels of uncertainty (yes, there are actually more than our list!😅), explain the basic definition, and the most frequent collocation.

なんだか or なんか for "Somewhat" or "Somehow"

なんだか, or its more colloquial casual version なんか, is an adverb for "somewhat" or somehow." This expression frequently goes with 〜気がする, as in:

- なん(だ)か熱が出そうな気がする。

- Somehow I have a feeling that I may develop a fever.

By adding なん(だ)か to the sentence with 〜気がする, it can muddy up your already-murky intuitive guess and make it sound more ambiguous.

もしかしたら for "Maybe" or "Perhaps"

もしかしたら is an adverb for "maybe" or "perhaps," and it's used when presuming something with a degree of doubt. This expression is often used with 〜かも(しれない), as in:

- もしかしたら風邪引いたかもしれない。

- Maybe I might have a cold.

Other adverbs like もしかすると, ひょっとしたら, or ひょっとすると express a similar nuance, but もしかしたら is the most common.

多分 for "Maybe," "Perhaps," or "Probably"

多分 is another word for "maybe" or "perhaps," but its certainty level is higher than もしかしたら and thus it most commonly translates as "probably."

Hence, it's typically used with 〜だろう/でしょう or 〜と思う, as in:

- 多分風邪だろう。

- I assume it's probably a cold.

- 多分風邪引いたと思う。

- I think I probably have a cold.

But it can also be used with other expressions such as 〜かな, 〜かも(しれない), or 〜はず.

恐らく for "Probably"

恐らく also usually translates to "probably", but its certainty level is higher than 多分, and it's often used to predict a bad outcome in the future. Also, the tone is more formal and literary, so it's best suited for formal conversations or in writing. Because of this nuance, 恐らく is generally used with a very affirmative claim, accompanied by an inferring expression, such as 〜だろう/でしょう or 〜と思う.

- 恐らく風邪だろう。

- I assume it's probably a cold.

- 恐らく風邪を引いたんだと思います。

- I think I probably have a cold.

In the above examples, the first one sounds like a written sentence or a blunt, self-directed thought, while the latter sounds like a formal and polite speech.

きっと for "Probably," "Surely," or "Certainly"

きっと is another adverb that could translate to "probably," but its certainty level is much higher than 多分 or 恐らく and thus it most commonly translates to "surely" or "certainly."

Hence, it can be used with an inferring expression, such as 〜だろう/でしょう or 〜と思う, but it can also go well with the expressions like 〜はず or 〜に 違いない.

- きっと熱が出る[だろう / と思う]。

- I assume I'll surely develop a fever.

- きっと熱が出る[はず / に違いない]。

- I'm sure I'll develop a fever.

Note that きっと also has other implications depending on the context. For example, the following sentence can have two readings depending on the context.

- きっと元気になるよ!

- I'm sure [I'll / you'll / they'll] be better soon.

Here, if you're talking about yourself, it expresses determination — you're determined to be better soon. When talking about someone else, on the other hand, it can express a strong desire — you really hope they want to be better soon.

確実に or 絶対に for "Surely," "Certainly," or "Absolutely"

確実に and 絶対に are the words for "surely," "certainly," or "absolutely," and they express a very high degree of certainty.

Hence, they can be used with an inferring expression, such as such as 〜だろう/でしょう or 〜と思う, but also go well with expressions like 〜はず, 〜に 違いない.

- [確実に / 絶対に]熱が出る[だろう / と思う]。

- I assume I'll certainly develop a fever.

- [確実に / 絶対に]熱が出る[はず / に違いない]。

- I'm sure I'll certainly develop a fever.

And they also go well with the plain form when expressing "realization" or "conviction."

- これ[確実に / 絶対に]インフルエンザだ。

- I'm certain this is the flu.

Between the two, 確実に centers on "certainty" based on the objective fact that there are no mistakes, changes, etc., wheras 絶対に simply means "absolutely" and indicates being uncontested by anything.

間違いなく for "Unmistakably" or "Definitely"

Another adverb with a very high level of certainty is 間違いなく, which indicates your unambiguous conviction and can translate "unmistakably" or "definitely."

It goes well with an inferring expression, such as such as 〜だろう/でしょう or 〜と思う or the plain form of a word that expresses "realization" or "conviction."

- 間違いなく熱が出る[だろう / と思う]。

- I assume I'll definitely develop a fever.

- 間違いなく熱が出る(わ)。

- I'm sure I'll definitely develop a fever.

Note that 間違いなく suggests that you have given your judgment that something is undeniably true based on some information you have. As a result, it carries a more formal tone when compared to 確実に and 絶対に, though it can still be used in everyday speech.

Quite Possibly the Conclusion

Whew! I know that's a lot of information to cover, but don't worry if you haven't memorized it all yet. This page can be a reference for you to revisit again and again until you've got it all down.

Keep in mind that the level of certainty described in this article is just an approximation, as the certainty conveyed can change depending on the context of the sentence, the person who uses the expression, and more.

Finally, like I mentioned, note that this article is just the tip of the iceberg; Japanese has tons of different ways for making statements less certain or more vague, including layering some of the above expressions, using double negatives, or more. Still, hopefully this is a good starting point for adding more nuance to your own Japanese, or helping you understand the level of certainty that someone is trying to express. Try and observe what sorts of statements Japanese people are making in real life and the context in which they're making these statements, and hopefully this sort of nuance will become second nature to you. Footnotes:

-

Note that there's also a feminine form of かな, which is 〜かしら; so you could swap the endings and say: 風邪かしら。(I wonder if I have a cold.) Feminine language, however, is becoming less and less common in Japanese. You're likely encouter 〜かしら mostly in creative productions, such as anime, novels, drama, or movies. ↩

-

Much like the English phrase "I wonder," 〜かな can imply that you're asking for advice or making a suggestion. Yet, 〜かな actually has a lot more implications than that! To learn more about it, check out our definitive guide to 〜かな. ↩

-

〜ですかな can also be used, but it's not common and is not the polite form of かな. The かな of 〜ですかな only serves the same as a casual かな, which indicates your own "I wonder" feeling. Combined with a polite statement, it usually expresses a request for agreement in a semi-self-directed manner. In other words, it would sound as if you were asking yourself about it, while simultaneously hinting to others that the question was addressed to them as well. Hence, 〜ですかな is polite yet casual expression, and therefore limited to those who are on the same or lower social status as you. As a result, it's rather uncommon in modern conversations, yet you may still hear old guys using 〜ですかな especially as a character-building device in creative writing or theatrical shows. ↩

-

Although you can say 風邪かな or 風邪かもしれない, you can't directly connect 風邪 and 〜気がする, as in 風邪気がする. This is because while 〜かな and 〜かもしれない are suffixes, 〜気がする is a phrase made up with the noun 気 (feeling) and 〜がする. To connect another words with the noun 気, you have to follow the grammar rule of noun modification. If you aren't familiar with it, check out the dedicated page! ↩

-

There is a similar expression 〜感じがする, but while 〜気がする means "I have a feeling that….," 〜感じがする means "It feels like that…" In other words, 〜気がする expresses that you're unsure yet get the sense that something is a certain way, and 〜感じがする describes how you feel regarding something. Imagine for instance that you met someone for the first time and get the impression that they're a nice person. Saying 優しい気がする conveys that you are unsure but have a feeling that they're probably a nice person. 優しい感じがする, on the other hand, is more of an expression that describes your feelings regarding the person. In other words, you can tell they're a kind person because of the warmth radiating from them, and 優しい感じがする describes this impression you have. ↩

-

Note it's strange to use 考える instead of 思うwith the example, as in 風邪引いたと考える as 考える (to think). This is because 考える alludes to deliberate thought. You can use it to say 風邪引いたと考えてみましょう (Suppose you have a cold), but it doesn't work when you're simply saying that you think that you have a cold. ↩

-

There's another 〜そう that's different from the 〜そう we're talking about in this section. The other 〜そう is used to report what you've heard, as in 田中さんは風邪を引いたそうだ (I heard that Mr.Tanaka has a cold) This can follow the past tense, so be careful not to get mixed up! ↩