Table of Contents

The Basics

Particle ね is a sentence-ending particle — a type of particle that adds nuance or tone to a sentence. A speaker uses ね when they want to imply that the listener agrees with what they're saying, or give the impression that they're both on the same page. For this reason, ね is often used to acknowledge or confirm something with the listener, kind of like tagging a question onto the end of a sentence in English, as in "…isn't it?," "…right?" or "…okay?"

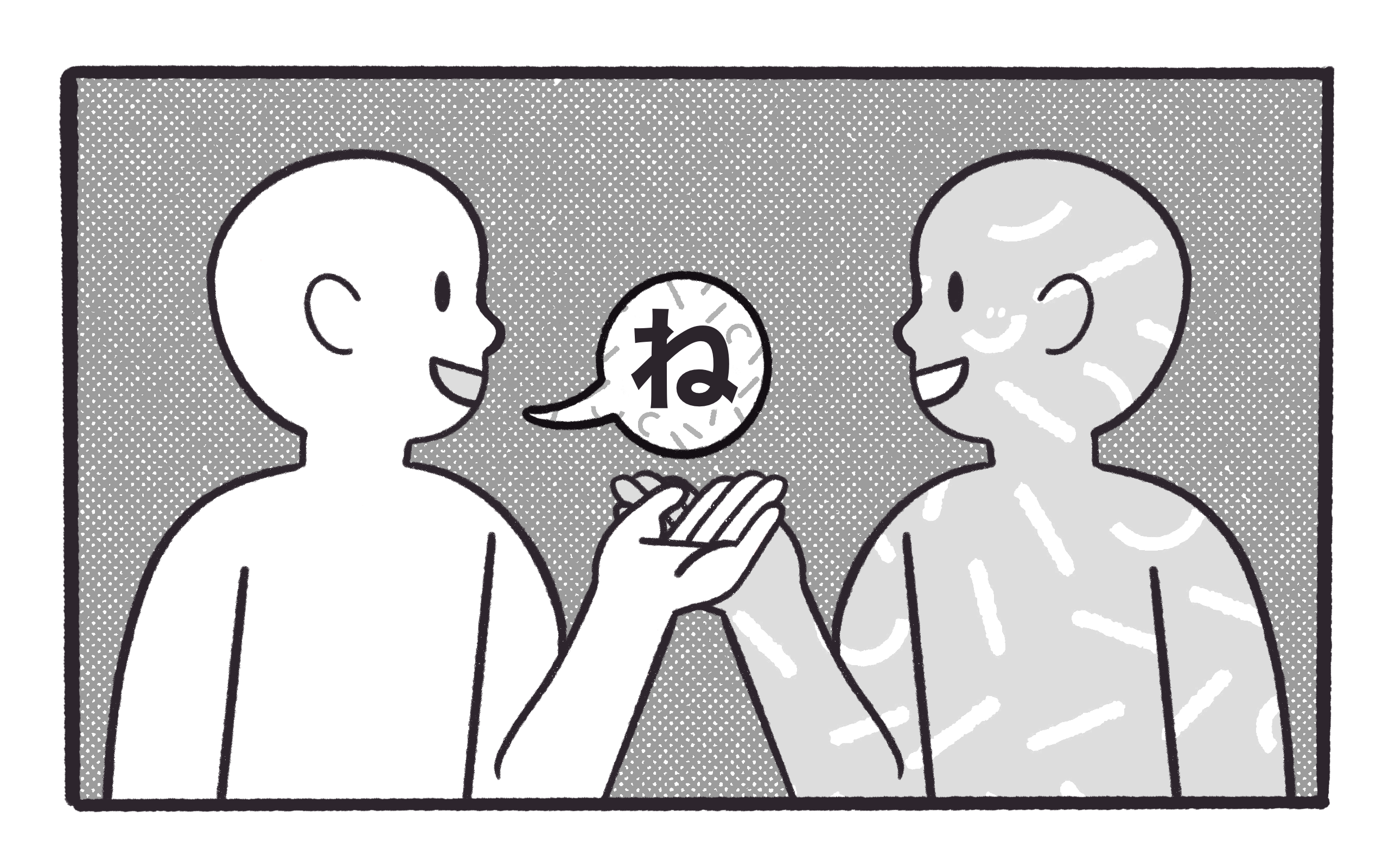

Conceptualizing ね

At the core of particle ね is the idea that it presents information as shared between the speaker and the listener. In the image above, you can see how both the speaker and the listener are holding the ね sentence in their hands, and the speech bubble combines visual elements of both. This represents the feeling of togetherness that ね adds to a statement.

For example, the following sentence states the fact that it's raining:

- あ、雨が降ってる。

- Oh, it's raining.

Without any sentence-final particle, this feels more like a self-directed, under-your-breath utterance than it does like a statement to inform someone else. By adding the particle ね, the statement is clearly directed at someone else, and the implication is that the listener will acknowledge or confirm:

- あ、雨が降ってるね。

- Oh, it's raining, isn't it?

In this way, ね can be used to make a sentence sound more conversational.

Patterns of Use

ね can actually pop up in a few different positions in a sentence. As it is a sentence-ending particle, we'll start off with when it appears at the end of sentences.

ね at the End of Sentences

You'll often see ね tagged onto the end of a sentence, and Japanese sentences can consist of just one word if the context allows it. For example, ね can come directly after a verb:

- 食べるね。

- I'll eat it, okay?

ね can also come directly after an い-adjective.

- 暑いね。

- It's hot, isn't it?

When the word before ね is a な-adjective or a noun, ね tends to add a feminine nuance. Since most speakers opt for a more gender-neutral tone nowadays, it's common to insert the affirmative だ or the politeness marker です before ね.

For example, here are your options with the な-adjective, しずか (quiet):

- しずかだね。

しずかですね。

しずかね。 - It's quiet, isn't it?

Isn't it interesting how all of these mean the same thing, but the nuance is slightly different? Using だ or です removes the feeling of femininity, and です elevates the politeness level! The same is true when you use ね with a noun, like 犬 (dog):

- 犬だね。

犬ですね。

犬ね。 - It's a dog, right?

Sometimes, another particle can be added after the な-adjective or noun, but in that case, it's still common to have だ or です before ね for that gender-neutrality. For example, we might want to add particle も to express "too," and this is how we'd do it:

- 犬もだね。

犬もですね。

犬もね。 - Dogs too, right?

ね Elsewhere In Sentences

ね generally comes at the end of a sentence, but it can also be used at the beginning or in the middle, to catch the listener's attention. Since this has a casual feel, ね is typically only used in this way between people who are on friendly terms, a bit like "hey!" in English. ね can also be repeated when used for attention, and in writing you'll often see it with the vowel part elongated:

- ね!

ねぇ!

ねーねー! - Hey!

You'll also see ね used to string together phrases with momentary pauses. When used this way, it communicates to the listener that the speaker intends to keep speaking, sort of like how some people say "like" over and over in Engish. So, like, do you get it?

- なんかね、やっぱね、今日はね、お風呂はね、入りたくないんだよね。

- Well, like, turns out, today, like, I don't wanna take a bath, mmkay?

That's, like, a lot of ねs! The idea that ね is used to suggest the speaker and listener are on the same page may explain this use of ね too. The speaker uses ね to express that they will continue talking, and this is done in a way that assumes the listener understands and is on board to keep listening. Often, the listener will somehow acknowledge that they are still engaged, either by nodding their head, or making a sound to indicate that they're paying attention. This is known as aizuchi, and is a fundamental part of Japanese conversation.

Uses of ね

There are various situations when ね comes in handy, and we'll examine the different uses one by one.

ね for Consensus and Togetherness

Since ね is used to present information as shared or mutually understood between the speaker and the listener, it can be used to build consensus or create a feeling of togetherness. For example, let's say you're hanging out with your friend on a very warm spring day. You may say to your friend something like:

- 今日、あったかいね。

- It's warm today, isn't it?

By adding ね to the end of this sentence, you assume that your friend has the same perception as you, and you're describing a jointly shared experience. In response, your friend might say:

- うん、あったかいね。

- Yeah, it is warm!

By using ね in response, your friend confirms that they are indeed on the same page. This kind of exchange is very common in conversation, and to reinforce feelings of togetherness. In many cases, you'll see these responses shortened all the way down to just the particle ね. So in response to you saying 今日、あったかいね, your friend could just say:

- ねー!

- Yeah!

In this case, you'll often see ね elongated as in ねぇ or ねー.

Of course, your friend might not be on the same page as you. In that case, they wouldn't use ね. When expressing an opinion which conflicts with the other person's idea, the particle よ is usually used instead:

- ❌ え、あったかくないね。

⭕え、あったかくないよ。 - What? It's not warm.

If you'd like to read a more in-depth comparison of these two particles, check out this article.

ね for Confirmation

Since ね shows that you believe you and your listener are on the same page, ね can also be used when the speaker wants to officially confirm something.

For example, let's say you made a reservation at a restaurant. When you arrive, you tell the waiter you have a reservation and give your name, say Satou. He may repeat your name to officially confirm it by saying:

- ご予約の佐藤さんですね。こちらへどうぞ。

- You are Mr. Satou who made the reservation, correct? This way, please.

In this example, ね adds the nuance that the waiter is making absolutely sure that he has understood it correctly.

For such a formal situation, you might be wondering why the question particle か was not used, as in ご予約の佐藤さんですか. This is because か indicates you don't know the answer and are simply asking a question. Since the waiter knows the answer, but is just double-checking for formality's sake, ね is more appropriate here.

Here's another example, where the speaker is presenting their statement with ね as though they want to confirm something, but the truth is they already know the answer. Let's say you are a suspect of a crime, and the police have been looking for you. When they finally spot you, they may confront you and say:

- 佐藤フグ男さんですね。署までご同行願います。

- You're Fuguo Satou, right? Please come with us to the police station.

In this case, the police are confident that you are the suspect. They use ね because they're presenting the knowledge as shared between the two of you. So even though they aren't really looking for your confirmation in this case, it still draws on the basic concept of ね, in that it presents the information as shared.

What about when you're not quite so confident? Well, a good option would be to combine particle ね with the other conversational particle, よ, to make よね. For example, imagine you run into a celebrity named Fuguo and ask them politely if they are who you think they are.

- あの、日本のアイドルのフグ男さんですよね?

- Hi, you're the Japanese idol Fuguo, right?

In such a situation, よね is better suited as it conveys the nuance "I think you're the pop star Fuguo. Am I right about this?"

ね in Requests and Suggestions

Particle ね can be used to soften requests and suggestions. It draws on the underlying concept of shared information to make requests and suggestions sound as though the listener is already in agreement. We'll cover two different patterns of this use in the following sections.

て Form + ね

One way to form a request in Japanese is to use the て form of a verb. For example, if your teacher told you to read this page on particle ね, they might say:

- この記事を読んで。

- Read this article.

Putting 読む (to read) into the て form turns it into a request or command. If the teacher adds ね to the end, as in この記事を読んでね, then it's as though they assume you have already agreed to do it.

In fact, this ね could be interpreted as a softener because you are not directly making a request, but rather checking in to see if someone is already on board with the request, almost like you have an unspoken agreement.

For example, imagine you're talking to your partner just as they are about to eat their lunch, and you're about to head out for work. You don't like to come home to a dirty kitchen, so you want your partner to do the dishes. In this case, you can use ね and say:

- 食べ終わったらお皿洗ってね。

- After you eat, can you make sure you do the dishes?

Using ね makes this sound as though it isn't a direct order. It carries the nuance of it being a request, but one that is basically already agreed to because you and your partner are on the same page about this.

〜よう + ね

Similar to a request, you can also add ね to a suggestion. In this case, it's attached to the 〜よう form of a verb.

When you make a suggestion with ね, there is a nuance that the listener is already in agreement. This can create a nurturing, parent-child kind of tone.

For example, imagine your kid has homework to do, but they're just watching YouTube videos and don't seem like they'll get around to it at all. You've waited long enough and finally say:

- そろそろ宿題しようね。

- It's time for you to do your homework, okay?

Just like with requests, the particle ね makes suggestions sound softer and less forceful since the statement is presented as though everyone is in harmony. It's a way to be both nurturing and slightly assertive at the same time. Of course, depending on how it is said, it might sound like you are passive-aggressively complaining about how your kid is not doing their homework by urging them to agree with it.

If you make a suggestion for something that you will also participate in, ね indicates your hope that the listener will agree to join you. This can create the nuance that you're making a promise rather than simply suggesting something.

Imagine you're saying goodbye to your friend and you hope to see them again. In this case, you can use ね and say:

- また会おうね。

- Let's be sure to meet again, ok?

Without ね, this would sound like a simple suggestion. By adding ね, it shows you are hoping your friend is on the same page and will agree with your suggestion.

Sarcastic ね

While so far, ね has mostly been butterflies and sunshine, it can also be used in a negative way. If you add ね to a statement that contains information the listener is clearly not aware of, you can sound a bit arrogant.

Imagine you are at a house party hosted by a wealthy individual and were just served a glass of scotch. It was the most flavorful scotch you've ever tasted, so you ask, "What's the name of this scotch?" and the host answers:

- それ?マッカラン・ラリックの62年だね。

- That? It's The Macallan Lalique 62 year old.

The party host's intention for using ね might be confirmation and togetherness, but depending on the context, they could also be adding a "everyone knows this" vibe to their sentence and talking down to you. Watch out for these ねs when they're spoken in a haughty, sarcastic tone.

Let's check out another example. Let's say you're struggling to eat with chopsticks, and your host sister says to you in a snotty voice, "Wow, can't you use chopsticks?" Clearly you're struggling so the answer is no, and you feel like this should be obvious. Asking you is freaking annoying! You could use ね to say:

- できないね。

- I can't, clearly.

In this case, using ね is like taking a "so-what" attitude. It's much more common to answer without any particle or with the particle よ to fill the information gap, unless you want to be defiant like this.