Where did all these honorifics come from? The answer is more interesting than we thought it would be.

You probably already know that it's important to add some kind of honorific at the end of a person's name in Japanese. Something like さん, for example. There are many others, of course, like くん, ちゃん, and さま, each with their own usage.

These name enders, or honorific suffixes, get more interesting and complicated the deeper you dig. We know this because we mined the very depths of Japanese honorific titles and name enders, and found tons that are read, written, or spoken by native Japanese speakers on a regular basis. For example:

- 殿 (どの): Mr. or Mrs., or Lord, back in feudal Japan.

- 嬢 (じょう): ~ess, as in "actress" or "seamstress." Used for all kinds of professions, from elevator operator to prostitute.

- 夫人 (ふじん): Used for Japan's First Lady, currently Abe Akie, or 昭恵夫人 in Japanese.

Where did all these honorifics come from? How relevant are they to your everyday Japanese? The answer to the first question is more interesting than we thought it would be. And the answer to the second is important to learn if you want to use the right honorifics in the right situations and not use the ones that went extinct more than a century ago.

- 殿 (どの)

- 様(さま)

- さん

- ちゃん

- たん、タン

- 君(くん)

- 氏(し)

- Defunct Japanese Name Enders

- Obscure, but Still Important

- Final Notes on Using Japanese Name Honorifics

- Download the Japanese Name Honorifics Study Sheet

Prerequisite: This guide is going to use hiragana and some katakana, so we highly recommend you learn them beforehand by reading our guides. Don't worry! They can be learned in a day or two—just come back when you're ready.

Before you move on: why not listen to this little ol' podcast we recorded about Japanese name enders? It goes over most of the honorifics covered in this article, but we dig deeper into real experiences we've had using name enders in Japan. It'll definitely add an extra dimension to what you're about to read.

And if you want to hear our voices in your ears more regularly, subscribe to the Tofugu Podcast, why don't you? That way, you can save this episode for later and use it as a review for the name ender knowledge we're about to drop on you.

殿 (どの)

This very old name ender predates the common ones we use today like さん, 君 (くん), or ちゃん. 殿 (どの) was a name ender for lord-types, which came into existence because of big butts (I cannot lie).

Here's how it happened: 殿 came from the kanji 臀 (しり), which means buttocks. If you have a big butt, you remain stable when you sit down. Because of this, 殿 came to refer to "a big, stable house or building." Why? Because big, stable buildings are, like big butts, big and stable.

Back in the day, who lived and worked in big, stable buildings? Buildings like palaces (宮殿 and 御殿) or shrines and temples (神殿)? You guessed it: nobles or high-ranking folks in society.

Big, stable buildings are, like big butts, big and stable.

Stick with me, because we're getting close to the payoff. In Japan, it's considered rude if you're too direct. For nobles and high-ranking people, calling them by their name was too direct. So it came to be that people would refer to them as buildings to sidestep using their names. It would be like referring to me as "The House of Michael" instead of just "Michael."

Over time, 殿 moved into the realm of government ranks, such as the 関白殿 (Chief Advisor to the Emperor). At first, the honorific was used mainly in writing. But people began employing it in conversation, too. Eventually it became common to use 殿 with regular folk, which lowered the degree of respect it imparted.

The Japanese language needed a new name ender to take that top spot, and 様 (さま) stepped in to fill the gap.

How 殿 (どの) is Used Now

As you saw, 殿 went through quite a few changes. Even though it's an incredibly old name ender, it's still around. Here are some usage points to consider:

- When 殿 is used, it's usually written, not spoken.

- 殿 is normally used after a full name.

- Sometimes it's used after a post/position name, such as 部長殿, but you shouldn't use it with a name + position (as in 鈴木部長殿), because you're doubling up on honorifics.

- 殿 was originally used for (very) high-ranking people. These days it's typically used for lower-ranking people—except in business/official documents, which conventionally use 殿.

- On business/official documents, 様 (さま) can be switched to 殿, though 様 is more common. More and more public/government offices are changing from 殿 to 様.

- That being said, citizens might still use the convention of writing 殿 when it's to a government office.

- In situations where 殿 is used in writing, 様 or さん will be used in conversation.

- 殿 is usually used as the name ender on diplomas and certificates. When the name is read and presented, it's read as 殿 and does not get replaced with 様.

- 殿 can be used sarcastically to say someone is acting high-and-mighty or entitled.

様(さま)

With 殿 becoming too common to use with real bigwigs, the Japanese language needed a new name ender to properly respect nobility. During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), if you were trying to avoid saying someone's name directly, you'd use 様 (さま).

The kanji for 様 was originally written as 樣, and its first use as an honorific was when you wanted to talk about someone indirectly. At this time, 様 meant "around there," so this honorific was like talking about a person's general location in relation to you, rather than naming them specifically.

But, like 殿 before it, people started using it as an ender for building names. If adding 殿 was polite indirectness, 様 was extra polite indirectness. Instead of calling someone "House of Michael," they would call them "Around the House of Michael." Double indirect bonus points!

To use some real, old world examples, the Emperor who lived in 御所 (the Imperial Palace) would be called 御所様 or 大御所様. A daimyō who lived in a 屋形号 (small castle) would be called 屋形様.

How honorable was the new honorific 様? A Portuguese book of Japanese grammar written in the Edo period (1603–1868) ranked four honorifics used at the time—殿, 様, 公, and 老. The highest ranking, two spots above the formerly-most-honorable 殿, was 様. That's what happens when you start letting commoners use your name enders!

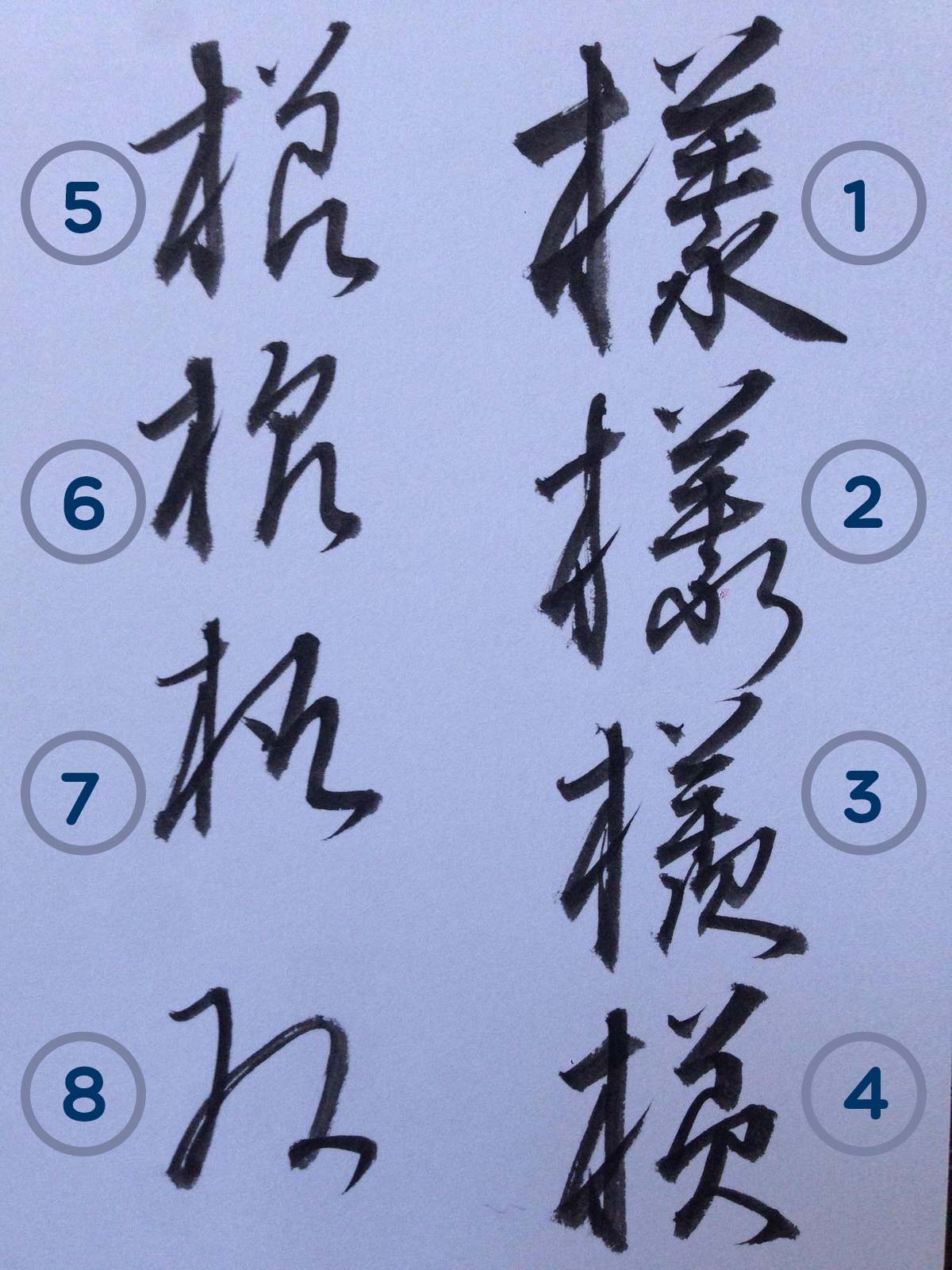

様 was such an honorable honorific that there were even different ways of writing the kanji that communicated various levels of politeness. The image below demonstrates this:

As you can see, the 様 kanji is written eight times, each time a little bit crummier. When you were writing to someone back in the day, you would write their 様 according to their status in relation to yourself. Here are the names of these different 様 writings along with descriptions of how they were used:

When you were writing to someone back in the day, you would write their 様 according to their status in relation to yourself.

- 永様 (えいざま/えいさま): Written in kaisho, the printed, square style of handwriting. Writing this way transforms the lower-right radical into 永, which is the old way of writing 様. Very fancy. You would use this when writing to someone of higher status than you.

- 永様 (えいざま/えいさま): The same as above but slightly less fancy. As such, it's slightly less respectful.

- 次様 (つぎざま/つぎさま): The 永 part becomes 次. This is used for people a little higher in status than you, or someone who is your equal.

- 美様 (びざま): The right part of 様 is written like 美 in sōsho, a type of cursive. This is similar to 次様, but a little less respectful.

- 平様 (ひらざま): Broken and flatter than the other 様 styles above it, this was used for someone who is the same or lower in status than you.

- 平様 (ひらざま): Slightly more deformed 平様, and thus slightly less respectful.

- 平様 (ひらざま): Even more slightly more deformed 平様, and even less respectful.

- 蹲様 (つくばいざま): Using this would be considered pretty rude. The name means that the 様 is "lying flat on its hands and knees" in a kind of groveling bow called 土下座 (which you can read about in our bowing guide).

Not pictured are two other forms of 様 you'll see written today:

- 水様 (みずざま/みずさま): This is the current 様 we use now. It was used for lower-status people back in the day.

- さま/サマ: Today, you could write 様 in kana in a casual message to your friend to avoid sounding overly stuffy. But there's nothing honorific about it, so stick with kanji in more formal situations.

How 様 is Used Now

Even though 様 is a very respectful name ender, and it may seem like you'll never use it, there will be times when it's appropriate. Here are some of the times you'll encounter 様 or need to use it yourself:

- It usually comes after a full name or surname.

- Nameplates for hospital patients may use 様, but 殿 is more common.

- The media uses the name ender 様 when referring to the royal family (naturally)—even the tiniest, bittiest baby.

- In emails, people often address clients, customers, and superiors with 様.

- You can't use 様 directly after positions or titles, like president or principal. 人事部長様 is incorrect, but 人事部長のコウイチ様 is correct.

- Groups like the Japanese Communist Party, who believe all people are equal, don't usually use 様—not even for the Emperor.

- National organizations and the Imperial family do not refer to the Emperor using 様. Instead they use 陛下 (Majesty) or 殿下 (Highness).

さん

Eventually, the honorable, venerable, and all-around superior 様 name ender fell into the hands of common people. Yet unlike 殿, which lost its status as number one, 様 remained intact because it transformed with common use: the あ dropped off the end of さま, leaving us with さん.

Hey, I bet you've heard this one before, Readerさん. And that's all the history there is to the most famous name ender of all!

How さん is Used Now

さん can be used for men and women, young and old—just about everyone. You can and should use this name ender quite often. But to make sure you use it right, try to abide by these rules:

- さん is by far the most common honorific in conversation.

- さん is used for both men and women, though in school, さん is most often used for female students, and くん for male.

- Don't use さん (or any other name ender, for that matter) when referring to yourself.

- Use さん with someone you don't know well or anyone you're not close to.

- さん can be used to pay respect to someone with a higher status than you.

- You usually put さん after someone's surname, but if you get to know them a little better, it's okay to add さん after their given name. Make sure you know the person pretty well, though.

- It's common for Japanese people to add さん after a foreigner's given name, because most people in Japan know that foreigners are called by their first names.

- Some people add さん to companies, groups, and teams. This is done to be polite when talking with someone who works at a company. For example, if you referred to our company as just Tofugu, we would be offended. Call it Tofuguさん, and you're on safer ground.

- さん is used for names of people in your family, especially those older than you: お父さん (father), お母さん (mother), お姉さん (older sister), etc. 様 was used for these names in the past, but today お母様 sounds archaic.

- Recently, some young people have been calling their 赤ちゃん (babies) 赤さん because it sounds funny. Kids today and their trends.

- It's common to add さん to animal names, especially when talking with children.

- Similarly, you can attach さん to inanimate objects like 冷蔵庫さん (Mr. Refrigerator) or おいもさん (Ms. Potato). It sounds courteous, cute, and kids like it.

- A lot of job titles end in さん, like 本屋さん (bookseller).

ちゃん

There's no etymology for the name ender ちゃん, but the popular consensus is that it evolved as a baby-talk version of さん. It makes sense. Whenever you have a widely-used word, kids in any country are going to mangle it with their baby mouths. Kids in Japan often have trouble pronouncing さしすせそ/たちつてと, and transmute it into しゃししゅしぇしょ/ちゃちちゅちぇちょ. Thus, さ became ちゃ, and suddenly we had a name ender to call kids, small things, and cute things.

How ちゃん is Used Now

Now we're in dicier territory than with さん. You can't use this name ender with just anyone. This is a term of endearment for family members, close friends, lovers, and pets. Use with caution (and with the notes below)!

Don't use ちゃん with anyone higher in status than you. Would you call your boss "Sweetie?"

- Don't use ちゃん with anyone higher in status than you. Would you call your boss "Sweetie?" Make sure you know the person well before adding ちゃん to their name.

- ちゃん is used frequently within families. It's common to hear kids call their grandparents おじいちゃん and おばあちゃん, and call their siblings おにいちゃん and おねえちゃん. Sometimes kids call their parents おかあちゃん and おとうちゃん, but this is slightly less common.

- ちゃん commonly comes after a given name. Sometimes the given name will be shortened for that extra dash of cuteness (e.g., コウイチちゃん becomes コウちゃん).

- If used with a surname, as in 森ちゃん, it imparts the same feeling as a nickname.

- It's used for girls more routinely than boys, but can be used for both (especially in childhood).

- People in the Kansai region, especially Osaka, add ちゃん to everything. あめちゃん (Li'l Mr. Candy), イモちゃん (Li'l Ms. Tater), うんこちゃん (Li'l Mr. Doodoo)—you name it.

- It's actually not so bad to add ちゃん to your own name. If other people have given you a nickname with ちゃん, it might be okay, around them, to use that nickname for yourself.

たん、タン

And so it came to pass that さま begat さん, and さん begat ちゃん, and ちゃん begat たん. If ちゃん is the baby-talk version of さん, then たん is the baby talk of baby talk! When you want to sound cute, you can't do much better than this.

That said, you may not hear this in everyday speech. When adults talk to babies, たん is common, and there are a few cartoon characters, like ノンタン and うーたん, who have it in their names. But other than that, usage will be limited to some very specific situations.

How たん is Used Now

Here are the situations in which you're most likely to find たん:

- Couples or people in love might use the name ender たん when addressing each other. This is usually done in private, since it can be embarrassing to talk like a baby in public. It depends on the couple, though.

- Adding たん to your own name is rare and typically only done by women. Hostesses and prostitutes are known to use たん with their own names, because a lot of customers prefer it.

- Some celebrities add it to their stage names, the first of which was Mizumori Ado, who called herself 亜土タン in the 1970s.

- In 2015, among some sixty other nominees,「○○たん」was nominated as one of the most popular new buzzwords of the year. It just goes to show: it's not all that strange when たん is trending.

- Of course, there are plenty of anime and manga characters with たん in their names, like さくらタン from Cardcaptor Sakura and ブリジットタン from Guilty Gear. But even real-life Japanese politicians get the name ender when the media deems it necessary. In 2005, Diet member Satō Yukari received the nickname ゆかりタン from the press.

- たん is widely used as a name ender for otaku.

- On the popular Japanese message board 2ch, people use たん with each other, either as an honorific or as a way to talk down to someone.

- Because of Twitter's character limit, some people use たん instead of ちゃん.

- Online, たん might be written as タソ (たそ) because it looks similar to タン.

- When you've got that moe feeling for someone, it's common to say「○○タン萌え!」. It's often used for little anime girls, but sometimes for anime boys.

- たん is used for what the nerds call 萌え擬人化 (moe personification). For example: ウィキペたん, the cute little girl personification of Wikipedia.

君(くん)

This one is both a name ender and a pronoun. You've probably heard 君 (くん) in your romantic school anime, where teachers call all the handsome boys「○○君」.

But it wasn't always a name ender. It began its life (and continues to be) the pronoun 君 (きみ), an honorific used only for the ruling class and gods. Today, however, we use 君 (きみ) as a casual "you."

Based on the equation "きみ = high class," it was eventually attached as a name ender to goods and locations that were considered superior or valuable. Soon enough, きみ was associated with people who were loved and respected, and women especially began using it for men they loved.

As society developed and a ruling class emerged, its usage expanded to include the heads of government. きみ was used for the Emperor, the leaders of powerful families and clans and, eventually, entire clans whose statuses were worthy of きみ. (This was actually a different きみ which used the kanji 公; over time, however, the 公 and 君 versions of きみ blended together.)

Of course, words don't stay the same for long, and eventually the high, respectful level of 君 was transformed into the second-person pronoun "you." Suddenly, usage of this word was widespread. Because it shows love and respect, きみ carried an honorific connotation. Yet this time it was a really general honorific connotation.

You've probably heard 君 (くん) in your romantic school anime, where teachers call all the handsome boys「○○○君」.

Eventually, the respectfulness of きみ was almost completely extracted, and the name ender became just a general "you," equivalent to 僕 (me). That's why "just between you and me" in Japanese is「僕と君との間柄だから」, using 君 and 僕 together.

All these seismic shifts in the word きみ happened before the end of the Edo period. But there was one more change in store: the one we've been waiting for. As the Tokugawa Shogunate came to an end, rigid samurai classes all went out the window. At this time, 君 received a second reading, くん, which is a name ender used to pay respect to anyone and everyone without acknowledging any kind of complicated, samurai-style hierarchy. The chairman of the Diet of Japan began using 君 with Diet members, and the tradition continues to this day.

How 君 is Used Now

Of course, 君 is used all over Japan for all kinds of people, young and old, and not just for Emperors and Diet members. Here are some usage notes for when you want to use this egalitarian name ender:

- 君 is more casual than さん.

- Don't use 君 with someone of higher status than you.

- 君 can come after a full name, given name, or family name.

- You usually use 君 with people of the same or lower status than you.

- It can be used for either gender, especially in formal and business situations, but outside that 君 is most often used for boys and men.

- At Keio University, founder Fukuzawa Yukichi is called 先生, and all other teachers and students use 君 with each other. This is a rare case, and we know of no other schools that do this.

- きゅん is the baby-talk version of くん. Because たん is mostly reserved for moe girl characters, きゅん was made specifically by nerds for moe boy characters. It's very rare to see this outside of the Internet.

氏(し)

This name ender has some real history behind it. Hop into your time machine, because we're going alllll the way back to the Yayoi period (300 BC–300 AD), when Japan transitioned from a hunting-and-gathering society into an agricultural one.

This was a time of clans called 氏族 (しぞく). These clans were made up of people bound by blood, marriage, or ancestry, and they defined who you were. Clan names were family names called 氏 (うじ), which stemmed from occupation or region, or were given by the Emperor. Some examples include:

Region 氏

- 出雲氏、尾張氏、和邇氏、穂積氏、吉備氏、葛城氏、蘇我氏、毛野氏

Occupation 氏

- 物部氏、大伴氏、阿曇氏、額田部氏、膳氏、日下部氏

氏 Given by the Emperor

- 藤原氏、橘氏、源氏、平氏、豊臣氏

You can learn more about the importance of clan names in this article we wrote about the history of Japanese names. Long story short, clan names were transformed into family names 1,500 years later in the Meiji period (1868–1912). But by this point, the pronunciation changed from うじ to し, and was attached, when the situation called for it, as a name ender for all family names.

How 氏 is Used Now

氏 is one of the most ancient name enders on the list. But you can still use it in your everyday Japanese, provided you know how and when.

- 氏 is used like "Mr." or "Mrs.", but only in the third person, usually in writing.

- Long ago, 氏 was used mainly for men, but today it's used for women, too.

- 氏 normally comes after a family name and sometimes after a full name.

- 氏 isn't typically added to a given name only, but recently people have been attaching 氏 to the end of usernames online.

- You don't normally call someone「○○氏」in conversation, but some otaku and young people do this to be hip.

- The word for boyfriend is 彼氏 and the 氏 here is honorific. Before 1930, it was simply 彼.

- The honorific 氏 can sometimes give the impression that someone is a gentleman or lady. For example, these Line stickers are called ねこ氏と仲間たち. The 氏 adds the feeling that this cat is a salaryman or someone of status.

Defunct Japanese Name Enders

As we've seen so far, honorific name enders have gone through many changes from their time of creation up to today. But sometimes they change so much that they fall out of use completely. Still, just because something is defunct doesn't mean you don't have to know about it. The following name enders may still come up in text or conversation, and if you don't know what they are, you'll be lost. And while you may not use these name enders much, if at all, it's still important to be familiar with them.

嬢(じょう)

嬢 is used as an honorific ender for both names and occupations.

The old kanji for じょう is 孃, which meant "fat woman" or "mother." But over time, the definition shifted to "daughter" and "girl," and the kanji became 嬢.

Traditionally, this was used after the name of an unmarried woman in the same way 君 was used for boys and it was equivalent to 君 in that way.

Over time, it became a more respectful word, お嬢様, used to describe girls who had social standing. Because of this, the use of 嬢 as a name ender is a kind of sarcastic putdown nowadays—like calling a little girl "princess." Today, the original, serious usage has all but disappeared.

However, 嬢 is still used an ender attached to women's jobs—in this case it has an "actress/seamstress/~ess" quality. For example:

- ウグイス嬢: a female announcer at a baseball stadium

- 受付嬢: a female receptionist

- エレベーター嬢: an elevator operator

- キャバクラ嬢: a hostess at a kyabakura

- ソープ嬢: a prostitute at a soapland

The last two have given 嬢 certain connotations. Kyabakura is a portmanteau of "cabaret" and "club," and they're places where beautiful ladies will light your cigarette and flirt with you for a fee. These hostesses are called キャバクラ嬢 or キャバ嬢. Soaplands are basically brothels and baths, and the women working there are called ソープ嬢. So the word 嬢, especially as an ender for female occupations, has taken on an association with the sex industry—another reason it isn't used loosely.

女史(じょし)

The name ender 女史 was attached to the end of a woman's name and had the feeling of "madam." Originating in China, it was used for intellectual ladies of the court in charge of maintaining records and enacting ceremonies for the Empress. The kanji 史 refers to someone who deals with documents.

During the Nara period (710–794), when Japan was copying just about everything from China, the word 女史 was adopted and used in the Ritsuryō Code, a Japanese legal system based on the Chinese model. At this point, 女史 wasn't really used by people in conversation, but was instead reserved for official documents.

Then, in the Meiji period, the meaning of 女史 came into use as a female equivalent of 氏. It became an honorific for notable women of high social status.

At first it was used to pay respect to notable women of the time—women like Higuchi Ichiyō, Yosano Akiko, and Hiratsuka Raichō. This usage spread nationwide. Unfortunately, however, envious men began using it derogatorily to ridicule intellectual women. Eventually, usage of 女史 fell out of favor altogether, and people began using 氏 for both men and women. Today, 女史 is considered archaic, and no one uses it at all.

卿(きょう)

卿 is a name ender attached to positions in government office. It originated in the Heian period (794–1185) under the Ritsuryō Code, and was used for government employees and nobility.

This name ender is not really used in Japan today, but you'll see it attached to foreign names with some title or honor. "Lord" and "Lady" is often translated as the name ender 卿. For example, Lord William Bentinck, the Governor-General of India in the mid-1800s, is ウィリアム・ベンティンク卿 in Japanese.

Perhaps the most famous 卿 among children in Japan (and the rest of the world) is Sir Topham Hatt, a.k.a. The Fat Controller, from Thomas the Tank Engine. In Japan he's called トップハム・ハット卿, and no one deserves the title more than he.

公(こう)

In the Nara period, the name ender 公 came over to Japan with the rest of the imported Chinese culture. 公 was used as an honorific for ministers until the early Heian period, when its usage expanded. Servants would use 公 with their masters, regardless of rank. The mighty daimyō Takeda Shingen (武田信玄), for example, would have been called 信玄公. This usage lasted until the Edo period.

In the Meiji period, 公 was used as an honorific name ender for a prince or duke. 公爵 is the word for "prince" or "duke," so naturally 公 would follow their names. A duchess or princess was called 公爵夫人, literally a "prince wife."

Eventually the usage of 公 expanded to include high-ranking people of all stripes, including the elderly and one certain loyal, waiting-by-Shibuya-Station dog, Hachikō (忠犬ハチ公). Poor puppo!

Of course, rowdy youths got their hands on this venerated name ender and started using it as a derogatory way to yell at authority figures like teachers (先公) and the police (ポリ公).

Over time, people stopped using 公 altogether. If you hear it today, it's in reference to a historical figure. 🐶

Obscure, but Still Important

This small group is made up of honorific name enders that are regional, situational, or rarely used. Still, they're good to know for when you eventually hear them, or if you plan to travel or live in regions where they're used.

やん

やん is a super friendly honorific attached to a nickname. An evolution of さん, it may have originated in Western Japan, but today it's used almost everywhere. Call your friends みーやん or まさやん, and see how they react!

りん

りん is super friendly and casual, too, and only attaches to nicknames. It's used mostly for girls and became popular in the 1980s, when pop idol Nakayama Miho took the stage name her producer had given her: みぽりん. Almost forty years later, this name ender is still used from time to time, but it's much less common than ちゃん.

夫人(ふじん)

夫人 is a name ender you won't hear often, though it's still used in formal settings. It's reserved for women who are married to someone of high social status. For example, the First Lady, Abe Akie, the wife of our current Prime Minister, is called 昭恵夫人.

御中(おんちゅう)

If you're sending a letter to an organization, school, or any kind of group that's not an actual person, you use the name ender 御中. Pretty specific. It's used only when corresponding, in writing, with a group. 御 is a prefix used to add politeness to a noun and 中 refers to a group of people.

Say you are sending a letter to Koichi of Tofugu. You would write「Tofugu コウイチ様」. But if you're sending it to Tofugu in general, you would use「Tofugu 御中」to address the many hardworking people at this well-respected company.

尊(そん/みこと)

This small group is made up of honorific name enders that are regional, situational, or rarely used.

尊 is used as a name ender for objects of worship in Buddhism and Shinto. The guardian deity of children, Jizō, is 地蔵尊 (じぞうそん), for example.

This name ender started out as one of the ranks of Taoist Gods in China. When Japan started copying the style of Chinese literature in the Nara period (710–794), 尊 was imported and used for the native Japanese word みこと, which was a name ender for gods and nobility. Until then, it had been written as 命.

At that time, high-ranking nobles (みこと) wanted to distinguish themselves from the lower status nobles (also みこと), so they adopted the new writing 尊 and attached it to themselves rather than 命.

But the writers of the first Japanese historical record, known as the Kojiki (古事記), didn't use the new Taoist kanji for みこと and instead only used 命 for both high and low-ranking nobility. And so, over time, the usage of 尊 and 命 became unclear (and remains that way). Today 尊 (そん) is used exclusively for Buddhist deities and objects of worship, and 尊 (みこと) is used for Shinto deities. Either way you slice it, it's gods only, no nobles allowed.

Final Notes on Using Japanese Name Honorifics

And that's all the name enders and honorifics we have. And by golly, we are 99% certain the ones we left out will not be relevant to your life in any way.

Before we end, we wanted to leave you with a few notes about honorifics in general that should help you understand and use them better.

- When you use a name honorific, you usually use honorific forms of verbs in the rest of the sentence too. For example:

- ⭕ コウイチ社長がパンを召し上がっている。

- ❌ コウイチ社長がパンを食ってる。

- Honorific name enders or pronouns are often used to make fun of people. If you have someone you'd like to ridicule, slap 様 at the end of their name, and use it sarcastically.

- If you are talking about someone in your group to another person outside that group, don't use name honorifics. For example, we at Tofugu wouldn't call our boss コウイチ社長 when talking with people outside the company. To outsiders, we'd just use plain コウイチ.

- When multiple people's names are listed for a news report, honorifics are often left out, but after saying 敬称略 (honorifics omitted).

Download the Japanese Name Honorifics Study Sheet

It can be hard keeping all these name enders straight in your head, especially when you're on the go (let's say, traveling through Tokyo to meet a new group of people).

This printable, smartphone-friendly reference sheet would come in handy in those types of situations. You can get your honorifics in order, right before the big meeting with Principal Boss.

If you're already a Tofugu email subscriber, you'll get this in your inbox. But if not, just subscribe here to get the file right away, and get all future giveaways sent straight to you. Plus, we'll tell you about new language articles (like this one), send you Japanese lessons, and NOT email you useless garbage.