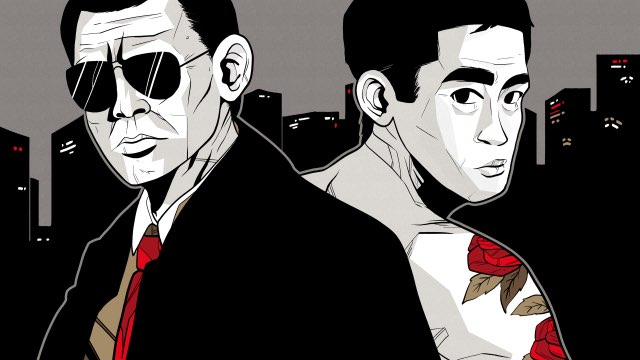

2014 has proven a sad year for Japanese cinema with the passing of two legends: Ken Takakura and Bunta Sugawara. Although close in age, the two came to represent opposing eras of yakuza cinema – Ken Takakura’s honorable yakuza heroes of the 60’s gave way to Bunta Sugawara’s cutthroat yakuza criminals of the 70’s. The two actors symbolize the yakuza genre, making the close timing of their deaths somewhat apropo.

Yet simplifying their legacies would be a mistake as the two actors transcended the genre they grew famous for. As the popularity of yakuza films faded, both men showed versatility by taking on new roles. Ken Takakura acted in dramatic films and even got his feet wet in Hollywood while Bunta Sugawara kept closer to his tough-guy roots, starring in the Trucker Yarou comedy series. Both stars worked well into old age, starring in sentimental dramas like Ken Takakura’s Dearest and Bunta Sugawara’s My Grandpa.

Join Tofugu in celebrating the legacies of these amazing, genre-transcending actors. Choosing only a handful of movies from the hundreds they appeared in proved a challenge and the following recommendations mix things up, featuring a variety of works spanning the actors’ careers. So grab some senbei and fire up the old projector, Betamax or whatever you’re using nowadays – on to the movies!

Ken Takakura

A Meiji University graduate, Ken Takakura “was in the process of applying for a lifelong ‘salaryman’ position at the Toei film company in Toyko when, on the lot, he entered an audition on impulse” (Roger Macy). Soon after, Takakura debuted in Denko Karate Uchi (1957) and never looked back, pumping out hundreds of movies through Toei Studios.

Described as “brooding, dignified, (and) hard hitting,” Takakura played heroic characters with a sense of justice (Ben Beaumont-Thomas). And no term better describes Takakura’s performances than dignified. Even when playing a criminal, Takakura could radiate dignity with a single glance.

His characters aren’t perfect, but that makes their struggles easy to identify with. In lowly roles, we root for him rise above his situation. When in positions of power we hope he can see justice through.

Takakura’s acting prowess and English ability helped him land roles in pictures abroad. He made his western debut in the WWII film Too Late the Hero and went on to star in a handful of Hollywood films.

His empowering roles took on special significance in China where “Takakura’s 1976 hit Manhunt was among the first Japanese films to be screened in China after the Cultural Revolution” (AFP-JIJI). His role in Chinese director Zhang Yimou’s Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles helped solidify his position as a cultural bridge between nations.

I compiled this list hoping to exemplify the variety of Ken Takakura’s roles, from dignified yakuza to struggling police officers to hard-nosed baseball managers.

Abashiri Prison (Abashiri Bangaichi – 1965)

Take a trip to Japan’s legendary Hokkaido prison, a detention center similar to the US’s Alcatraz in fame and reputation. We all know Takakura’s good-guy character has a justified reason to be there, and part of the movie’s fun is waiting to find out why. All the while inmates try to pull Takakura into an escape plot he initially resists, but is given reason to consider. Will Takakura join the plan?

Hokkaido’s snowy landscapes provide a deep, beautiful black and white backdrop to this prison adventure. Despite some impromptu festival dances and scenic drives to labor areas, no one wants to end up in Abashiri Prison.

Abashiri Prison combines Takakura’s classic dignified persona with a strong cast and great plot. As a bonus for watching you’ll get a taste of Japanese prison life and learn why you don’t have to worry about dropping the soap in Abashiri Prison.

Demon Yasha (Yasha – 1985)

“A hyena with a conscious is no longer a hyena.” My favorite among Ken Takakura’s films, Demon Yasha tells the story of a yakuza who leaves a life of crime behind to move to Hokkaido. There he goes legit, becoming a fisherman, family man and respected member of his village.

Of course things don’t stay peaceful for long and trouble comes calling when a young, drug dealing “Beat” Takeshi arrives with his attractive girlfriend. Will Yasha be able to protect the village and continue living his new life? Or will his yakuza roots pull him back in?

Faced with deep temptation, Yasha becomes one of Takakura’s more troubled, complex characters. Demon Yasha kept me guessing on how it would all turn out. I enjoyed the film’s atmosphere and rhythmic, no-nonsense cinematography that gave it a “Beat” Takeshi-like movie feel.

Black Rain (1989)

East meets West in this police crime drama directed by Ridley Scott of Blade Runner fame. And boy does it feel like a Ridley Scott movie with its dark, brooding, confined locations and (where does it all come from?) smoke and steam. The movie’s eerie depictions of Osaka creeped me out as a kid and continue to do so today.

Circumstances force American cops, played by Michael Douglas and Andy Garcia, to venture into Osaka in pursuit of a ruthless yakuza named Sato. To do so they must cooperate with a Japanese cop (guess who!) who is caught between adhering to police protocol and helping the American cops apprehend Sato.

Ridley Scott makes sure Black Rain’s pace never slows by striking a great balance between plot development and action. The music, mood and style are pure eighties goodness, but my favorite aspect of the movie is Michael Douglas, Andy Garcia and Ken Takakura’s chemistry. I really enjoyed the interactions among the three, with Andy Garcia acting as the voice of reason in contrast to his strong-willed partners.

Black Rain is worth watching just to witness Takakura’s karaoke duet with Andy Garcia. Yuusaku Matsuda’s brilliant performance as Sato is also worth note, as it was one of his last.

Mr. Baseball (1992)

In Mr. Baseball Ken Takakura plays second fiddle to Tom Selleck, but that does nothing to undermine his contribution to the film. A struggling major-leaguer, Selleck’s stubborn character gets shipped to Japan where he struggles to adjust to his new life. Takakura plays the team’s equally stubborn manager whose job is on the line thanks in part to his new American import. The two bump heads, refusing to bend to cultural differences and the comedy-drama ensues.

All but forgotten in the annals of moviedom, Mr. Baseball shines at showing the difficulties a foreigner living in Japan faces. Although I had trouble relating to Selleck’s jerk of a character, his situations felt very familiar. I couldn’t help but cringe at some of his faux pas, recalling my own.

Despite Takakura’s great performance, to those who never experienced Japan, Mr. Baseball may feel like a forgettable comedy. But those that share some of Selleck’s awkward experiences will appreciate its realistic depiction of culture shock, or more appropriately, culture clash.

Dearest (Ananta e – 2012)

Takakura’s final film has a “it’s not the destination, its the journey” theme. Dearest sees Takakura trekking across Japan to spread his late wife’s ashes in her hometown. During the trip he meets all sorts of people, takes in the beautiful scenery and grows even closer to his late wife.

Dearest features a cast of popular actors including “Beat” Takeshi (Outrage), Koichi Sato (Unforgiven), Tsuyoshi Kusanagi (of pop group SMAP) and Haruka Ayase (Happy Flight). As a result, the film becomes more a celebration of Ken Takakura than a good movie in its own right. Like Clint Eastwood’s recent work, Dearest has sentimental themes, but lacks Eastwood’s punch and purpose. Still, I’m glad I joined Takakura for his last ride.

Bunta Sugawara

The gritty, bloody and chaotic Modern Yakuza Outlaw Killer served as my unforgettable introduction to Bunta Sugawara and a new world of Japanese cinema.

In an era where Akira Kurosawa was the face of Japanese cinema (fans had to dig deep to find Golgo 13 and Shogun Assassin) in the West, one thing was clear – Kurosawa this was not. Despite its descriptive title, the film’s violent, reckless style shocked me – and I’ve been a Bunta Sugawara fan ever since.

Perhaps Sugawara played badasses so well because he was, in fact, a certified badass. According to film reporter Mark Schilling,

Sugawara entered the Shintoho studio in 1958 after leading a scuffling existence on the fringes of Tokyo’s underworld that furnished material for his later roles. When the studio went bust in 1961, he left for rival Shochiku, but his career was treading water until former-gang-boss-turned actor Noboru Ando helped him join the Toei studio in 1967.

Sugawara’s resulting library of work steered the yakuza genre in a new direction. Audiences watched Takakura films, but they experienced Sugawara films – and occasionally showered afterward for spiritual cleansing (maybe that was just me).

Although best remembered for the groundbreaking Battles Without Honor and Humanity series, Sugawara went on to star in a variety of roles as a boxer, a trucker driver and even a police inspector.

Battles Without Honor and Humanity (Jingi Naki Tatakai – 1973)

The theme song strikes like a bolt of lightening and serves as a warning; this isn’t your usual yakuza film. Director Kinji Fukasaku’s gritty directing style means Battles Without Honor and Humanity doesn’t just look different from previous yakuza movies, it feels different. Based on true accounts of crime in post WWII Hiroshima the shaky camera, gratuitous blood and haunting locations give the film a life of its own.

And Bunta Sugawara is at the helm. A former soldier turned street hoodlum, Sugawara is sent to prison where his life becomes entangled with one of Hiroshima’s top yakuza families. The film and its sequels follow the ups and downs of Sugawara’s violence filled life of crime. Winner of the Kinema Junpo Awards for best actor and best screenplay in 1974 (IMDb), Battles Without Honor and Humanity is a Japanese film classic that shouldn’t be missed!

Truck Guys (Torakku Yarō – 1975)

Like Ken Takakura, Sugawara didn’t limit himself to the yakuza genre and Truck Guys provides a light, comedic alternative to his heavy, violence-laden yakuza films. Sugawara’s rough but lovable trucker character proved popular enough to spawn several sequels. Cheesy and campy in all the right ways, Truck Guys‘s bar fights, races, CB radio karaoke sessions and heartbreaks make for an entrancing hour and a half.

The Boxer (Bokusa – 1977)

The Boxer finds Sugawara playing a former boxing champion who turned his back on the sport at his peak, though no one knows why. Fate brings a eager young boxer to the former champ’s doorstep. Sugawara reluctantly agrees to train the young man, who brings hope to Sagawara and a band of hopeless misfits that rally around the two.

I’m a sucker for boxing films and The Boxer’s gritty montages, music, and film style quickly won me over. Sugawara and Kentaro Shimizu’s performances propel the film past rocky attempts at symbolism and campy seventies trimmings. Sugawara’s dignified character provides a refreshing change from his usual riff-raff.

Why did Sugawara’s character quit the sport? Will his protégé win and bring him and his supporters redemption? You’ll have to watch to find out!

The Man Who Stole the Sun (Taiyou wo Nusunda Okoto – 1979)

In The Man Who Stole the Sun, Sugawara jumps to the right side of the law, playing police inspector Yamashita. After stopping a gun-wielding maniac in a hostage crisis, detective Yamashita becomes a subject of fancy for Kido, a terrorist who just completed the construction of an atomic bomb. The Man Who Stole the Sun becomes a game of cat and mouse, with Yamashita doing his best to catch the criminal and protect the city before it’s too late.

Like many Sugarawara films, The Man Who Stole the Sun has a kinetic style that’s over-the-top and fun to watch. I loved witnessing Kido’s plan unfold; we witness him study, plan, steal materials, build a bomb, and then terrorize Tokyo before battling it out with inspector Yamashita.

A stirring and memorable soundtrack accompanies the plot and puts today’s uninspired, synthesized soundtracks to shame. As a testament to the soundtrack’s awesomeness, Yamashita’s theme makes an appearance in Evangelion 2.0.

“Individuals don’t need atomic bombs, nations do!” one investigator shouts when he learns of Kido’s intent. Like Terror in Resonance (Zankyō no Teroru), the recent anime series this movie undoubtedly inspired, The Man Who Stole the Sun explores the meaning of extreme destructive power, touching upon important themes while maintaining its true goal of entertainment.

My Grandpa (Watashi no Guranpa – 2003)

Even the badass Sugawara can’t avoid a sentimental ride into the sunset. Still, Sugawara stays close to his roots, playing an old yakuza in My Grandpa.

Instead of retiring to a quiet life, Sugawara leaves prison prepared for a head-on confrontation with his past. This includes settling the score with a rival gang, atoning for his best friend’s death and coming to terms with his estranged granddaughter.

Although a criminal, Sugawara doesn’t play his typical wild, ignoble yakuza character. Instead My Grandfather has the class of a Takakura gangster – a dignified criminal with reason and remorse. Less sappy than Takakura’s Dearest, My Grandpa transcends simple sentimentality by focusing on an empowered old man coming to terms with a haunting past and regret.

Bonuses!

International Gangs of Kobe (Kobe Kokusai Gang – 1975)

I imagined that if Ken Takakura and Bunta Sugawara starred in a movie together it would have resembled something like a yakuza-themed The Odd Couple, with Ken Takakura’s dignified yakuza having to pacify Bunta Sugawara’s crazy side.

In International Gangs of Kobe the opposite occurs; it’s Sugawara’s presence that brings out Takakura’s ruthless side. Although the two start off as allied gang members, Kobe proves too small a town for the giants of yakuza cinema. The gang splits into rival factions and Takakura and Sugawara settle their differences with violence. Tons of action and a notable cast make the unexceptional International Gangs of Kobe a load of silly yakuza fun.

Antarctica (Nankyoku Monogatari – 1983)

Do you remember that 2006 Disney movie called Eight Below? The one where Paul Walker leaves a bunch of sled dogs at a base in Antarctica during the harshest part of winter? Did you know the plot is stolen from – I mean based on the plot of Ken Takakura’s Antarctica? If you like dog movies then check Antarctica out, though calling it a Ken Takakura movie is a bit of a stretch considering it stars a bunch of dogs.

Spirited Away (Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi – 2001)

Although Ken Takakura appeared in enough English language movies to make him a familiar face in the West, Bunta Sugawara never gained notoriety overseas. His most recognizable role in the West consists of just his voice, as the multi-limbed boiler room operator Kamiji in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away. That’s right! If you watched the Studio Ghibli film in Japanese you’ve already experienced Bunta Sugawara!

The Projector Rolls On

Both Ken Takakura and Bunta Sugawara have been referred to Japan’s Clint Eastwood. However, Ken Takakura’s noble yakuza share more in common with the clean-cut cowboys of John Wayne’s old westerns. Clint Eastwood comparisons seem more appropriate for Bunta Sugawara, whose violent yakuza films changed a genre, just as Clint Eastwood’s violent spaghetti westerns did in the US.

But in the end the comparisons prove unnecessary. Ken Takakura and Bunta Sugawara were trailblazers of Japanese cinema and lynchpins of Japan’s domestic industry. Both actors survived the studio system and overcame typecast roles to become lifelong artists whose influence can still be felt today. Bunta Sugawara helped pave the way to the ruthless and shocking gangsters of Takeshi Miike’s yakuza films while Ken Watanabe followed Ken Takakura’s blueprint to fame abroad.

If you haven’t experienced these legends for yourself, please take the time to see their works and experience Japanese film history!