同人 (doujin): "same person," refers to a group of people with shared interests.

誌 (shi): short for 雑誌 (zasshi), which means magazine.

Put these together and you get:

Doujinshi (同人誌): a self published magazine or publication that caters to a specific group of people.

Let's flesh out this doujinshi definition a bit more.

For example, there are a group of people who want to see Sailor Moon fighting a Gundam. There's a doujinshi for that.

Another group wants to see Goku and Piccolo making sweet, sweet Saiyan-Namekian love, not to mention all the hijinks their hapa-child will get into. There's a doujinshi for that too.

These are examples of doujinshi where the artist steals characters, settings, and/or themes. It doesn't have to be this way, though. There are also self-published doujinshi works that are completely original, too. As long as it is a publication that caters to a specific group of people, it's considered "doujinshi."

With that, we have two main categories that doujinshi can fall under:

- Original (オリジナル) aka ichiji sousaku 一次創作

- Parody (パロディ) aka niji sousaku 二次創作

- 二次創作(にじそうさく)

- Derivative works, fan-made media based on established characters and properties

Ichiji sousaku (original) doujinshi are works that are not based off any existing manga, game, anime, or anything else. They are completely original amateur works and fairly straightforward. An amateur artist makes something and tries get people interested, either for fun or profit. Cool.

Niji sousaku (derivative works), on the other hand, are publications that borrow pre-existing characters and/or settings. An amateur artist takes someone else's characters, puts them in interesting situations, and sells it.

This would not work in America.

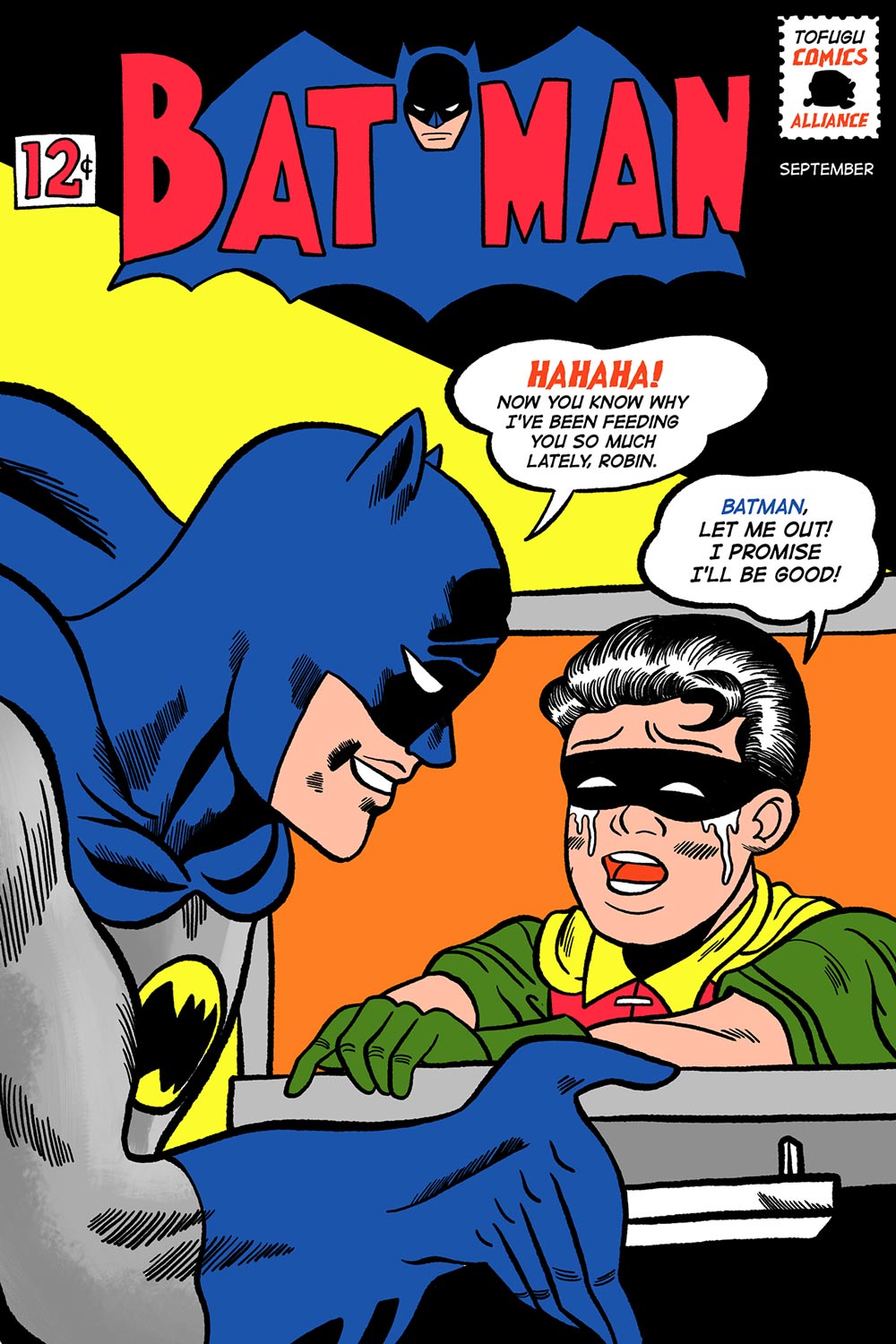

Let's say you've always wanted to read doujinshi where Batman pushes Robin into an open oven and bakes him alive. You use your artistic talents to write, draw, and publish the entire story yourself. You call it Batmannibal.

You share it on a fan fiction website and some people read it. DC Comics doesn't care. Everything's gravy.

But you get an idea: "What if people are willing to pay for the privilege of reading my story?"

You print copies of Batmannibal and take it to a local convention. To your surprise, you sell every last copy of your cannibalistic Batman comic. You've found your people, your doujin, and they love you! Your work is finally getting the attention it deserves (Also, you're getting some money). It looks like everything turned out allllr–

KA-PLOW!

Suddenly, DC Comics' Super (Lawyer) Friends crash through the ceiling, pummeling you with cease-and-desist beams.

A group of people want to see Sailor Moon fighting a Gundam. There's a doujinshi for that.

"Batman™ belongs to DC Comics, Inc. and its parent company Warner Bros. Entertainment," they say. "We won't let an unlicensed villain ruin Batman's good name. That's Zack Snyder's job."

And so your budding comic career is crushed beneath the foot of justice, and everything goes back to normal. The end.

This happens all the time in America. Derivative works projects are shot out of the sky (probably with a completely legal military-grade automatic assault rifle).

Star Trek fan film? Boom. Harry Potter online game? Blam. X-Men animated web series? KA-KORSH! (Sorry, I was running out of explosion onomatopoeias.)

Sure, there are fan projects in the U.S. that survive. Some even make money. But as soon as a project gets widespread attention, that's when the lawyers come for you. American companies can't squash everybody, but they do a good job keeping fan projects from getting too big.

In Japan, it's a completely different story. There are no lawyers crashing through the ceiling, no cease-and-desist beams. Copyright law exists of course, but it can't be enforced without a complaint from a rights holder. And Japanese rights holders don't complain.

They aren't allowing "just a few fan projects" either. There's an entire industry built around doujin creations, which includes fan-created novels, games, and even anime. This makes our original doujinshi definition pretty broad, expanding beyond the "shi" 誌 aspect entirely.

In all, there are an estimated 1,000 doujinshi sokubaikai 同人誌即売会 (doujinshi selling events) per year in Japan alone. Some are "all genre" conventions, while others cater to specific doujin groups (like cat ear manga). The largest of these conventions is Comiket, which attracts over 600,000 fans a year. In addition to conventions, there are plenty of online and physical shops that sell Japanese fan manga year round.

My point is, niji sousaku live in a legal gray-area, but nobody seems to care. This includes big publishers, professional mangaka, and even the current prime minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe.

But why don't they care? Why not prosecute to the full extent of the law? There are at least six reasons:

1. Respect

Many professionals respect amateur artists, having come from similar circumstances. They see niji sousaku as the first steps toward professionalism. For example, Clamp, one of today's most revered manga studios got their start making yaoi doujinshi for Comiket.

Naturally, professionals who started out borrowing popular characters don't want to squash young artists who are doing the same.

2. They Want To Maintain A Good Reputation

Artists and publishers are afraid litigation will alienate their customer base. Doujinshi artists represent their most hardcore fans, and prosecuting them might result in "negative reputational consequences." In other words, destroying a low profit fan comic could give the company an ogre-like reputation.

3. Acceptability

In Japan, Copyright Law can't be enforced without a complaint from a rights holder. And Japanese rights holders don't complain.

In Japan the use of pre-established characters is culturally entrenched to the point of acceptability. In fact, "borrowing" characters from other series has been common practice since the dawn of the modern manga and anime industries.

Mickey Mouse especially was used in pre-1950s akahon manga like it was nobody's business. Even the characters and stories of Tezuka himself were copied, repackaged, and sold all over Japan during the early parts of his career.

4. Doujinshi Is Considered Parody

From a legal standpoint, Japan considers niji sousaku "parody" rather than "counterfeit." SGCafe reported on Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's statement on the matter:

[Abe] said that Doujinshi must be treated more like parodies (in a legal sense) and not as pirated works like illegally streaming anime or uploading manga. He argued that doujinshi don't make much of a profit… and don't damage intellectual property rights.

5. Free Advertising

Niji sousaku offer a form of free advertising. Several of Japan's large mainstream manga publishers, such as Kodansha and Shogakukan use doujinshi manga markets for their own advertisement. The potential of derivative works attracting new fans to a series is huge and even a derivative works' small profits trickle upwards to the pockets of the original creators.

6. Cultural Hesitancy To Sue

In Japan "unnecessary" litigation is frowned upon. Because relationships are important, Japanese companies and individuals are less likely to sue. In the case of doujinshi, the amateur artists may become mangaka superstars in the near future. It doesn't make sense to ruin a relationship with the next Akira Toriyama.

Potential business dealings aside, derivative works usually have limited availability and profitability, and victory in court rarely yields meaningful profit. In this light, lawsuits against weak baby artists are seen as an unreasonable waste of time.

If doujinshi artists generally aren't worth suing, it's clear they don't make much money. Though some artists make it big, they're the exception rather than the rule. According to a survey of 4,000 doujinshi artists, most don't even make a living.

How Many Copies Doujinshi Artists Sell at One Event

- 2% reported selling 1,000 or more works

- 3% reported selling 500-1,000 works

- 47% reported selling less than 30

Who Are Doujinshi Artists?

- 40% are students

- 21% are full-time employees somewhere

- 21% are part-time employees somewhere

Why Do Doujinshi Artists Make Fan Comics?

- 4% say they do it for a living

- 22% do it to relieve stress

- 10% do it to become professionals

- 大手さん(おおてさん)

- Doujinshi artists who make it big and become professionals

After a convention is over, 60% of artists walk away without making a profit. Out of the 40% who do make a profit, they don't make much. The top 10% make around 200,000 yen (approximately $2,000 USD) at larger conventions. Not bad for a single day's work, but maybe not enough to move out of your parent's tatami room.

Though most doujin artists are hobbyists, a precious few "make it big" as professionals. They are known as Oote 大手 or Oote-san 大手さん, aka "big ones."

Though there are very few "big ones," they make a very big splash. If you're into anime or manga, even just a little, I'm sure you've heard of their work. By "borrowing" inspiration from original series like Princess Knight, Mobile Suit Gundam, and Aim for the Ace!, a generation of amateurs went on to create their own works like The Rose Versailles, Mobile Police Patlabor, and Aim for the Top!

Here are few examples of major anime and manga creators we wouldn't have heard from without good ol' doujinshi:

-

Kiyohiko Azuma: Accclaimed manga artists Kiyohiko Azuma has created fan-favorite titles such as Azumanga Daioh and Yotsuba To! (the latter is a great manga for beginners learning how to read Japanese). But he wouldn't have made it big without a little intellectual property theft. In high school, Kiyohiko honed his art and storytelling abilities by making Urusei Yatsura fan comics. Of course, no one would sue a high school student, but he continued this practice through college, entering the doujinshi community by creating and selling Sailor Moon fan manga. He's the original manga storyteller we know today because Kodansha didn't crush him with a cease-and-desist.

-

Chica Umino: Before creating the award-winning manga Honey and Clover and March Comes Like a Lion, Chica Umino made sold Slam Dunk doujinshi at Comiket. Her dream of becoming a mangaka started in elementary school, and her road to success had notable stepping stones, a major one being the fan comics she sold at Comic Market.

-

Gainax: Not all doujin are of the shi variety. There's also doujin games, novels, and of course anime. The most famous doujin anime group started as a college club and gave birth to an anime phenomenon – Neon Genesis Evangelion. Gainax embraced otaku eccentricities and fan service, making the company king of media by nerds for nerds. From the hand-drawn Daikon III and Daicon IV openings created for conventions in the 1980s, to recent hits like Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann and Kill la Kill, Gainax continues to give fans what they want.

-

Masami Yuuki: Masami Yuuki started out making Gundam parody doujinshi. Over time, this transformed into a serious standalone property, spawning a long running TV series, video releases, movies, and all sorts of merchandising. In 2015 the series saw its first live action release, one that included the construction of a life-sized Patlabor.

- Clamp: This three member group of teenage girls grew into a twelve member doujinshi circle. They made their professional debut with the manga RG Veda. Clamp parodied soccer manga Captain Tsubasa and created a yaoi versions of Saint Seiya before becoming an industry powerhouse with hits like X, Chobits, Cardcaptor Sakura and XxxHolic. Though they started out breaking copyright law, Clamp became one of the most prolific creators of super popular manga properties throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

Amateur doujin artists go pro so often, manga publishers set up booths at doujinshi conventions to scout for new talent. If there's a superstar among hobbyists, the publishers want to find them.

Big or small, all doujinshi fuel the anime and manga machine. If the fan comic hobby becomes a career, then there's more official manga to obsess over (and borrow from for future doujin projects).

If a doujinshi creator continues making only One Piece spin-off manga about the adventures of Buggy as pirate king (please someone make this), that's fine too. Their use of established characters adds legitimacy to the property and fuels fan passion. Fan interest in a One Piece spin-off manga doesn't mean they'll stop reading official weekly releases. Devotion to a niche doesn't weaken interest in the parent topic, it strengthens it.

By ignoring copyright violations, Japanese publishers have created a virtuous circle in which fan obsession and new talent is grown and harvested.

Unfortunately, there's a threat to manga and anime's tried-and-true system of growth and prosperity. In a few years, Japan could end up like America, swatting down fan creations left and right. All thanks to one greedy organization.

By ignoring copyright violations, Japanese publishers have created a virtuous circle in which fan obsession and new talent is grown and harvested.

The new president of JASRAC (The Japanese Society for Rights of Authors, Composers, and Publishers) has announced plans to expand their reach into art and literature. This includes manga and anime. As it stands now, JASRAC only polices the Japanese music industry where they manage 3.5 million songs, collecting fees from CD sales and use of songs on TV, radio, karaoke, and store loudspeakers.

If JASRAC feels they're owed money, they'll try and get it. They are infamous for cracking down on even the smallest of copyright violators. Here are a few of their greatest hits:

-

The time they destroyed the Japanese MIDI culture in the early 2000s.

-

The time they tried to fine over 200 small businesses for playing music on their ipods during business hours.

-

The time they tried to charge people for tweeting Japanese song lyrics on Twitter.

What is doujinshi to do against such forces? This is bad new for Japan's fan comics community.

I think author David Meerman Scott says it better than I could:

While I get that artists need to be paid for their work, putting draconian rules in place only seems to serve the JASRAC kingdom and keep them in power, it does not serve artists. Artists are best served when people learn about their work from fans. And fans love to share…

If niji sousaku doujinshi were stomped out by JASRAC, over time it could cripple the anime and manga industry. Passion generated by this niche fandom would dry up, and otaku money along with it. Fewer and fewer amateur artists would be discovered. The next great mangaka would become an accountant, all because JASRAC kept her from selling Doraemon fan slash-manga at Comiket.

These are the hardcore-est of otaku we're talking about. They should be celebrated, not squashed. They are attracting new fans to established series by creating "parody works." They're also attracting fans to new, original series, the kind that go mainstream and make publishers super rich in the near future. At the very least, doujinshi culture is producing large groups of people willing to wait in long lines to spend money on manga, anime, figures, goods, and more.

Doujinshi may violate copyright laws, but it isn't theft, at least not in spirit. Doujinshi is more like celebration, an ongoing fan party. Otaku are celebrating the characters and stories we love through creation and sharing. Some even celebrate the medium itself with new and original stories.

But in America, grumpy rights holding companies shut down the party by calling the cops. In Japan, companies let the music play because they realize the party's in their honor.