Translating Japanese is hard. Translating Japanese poetry is even harder. Beyond meaning, you have to capture feeling, emotion, and nuance. That's why one Japanese poem can have dozens or even hundreds of translations.

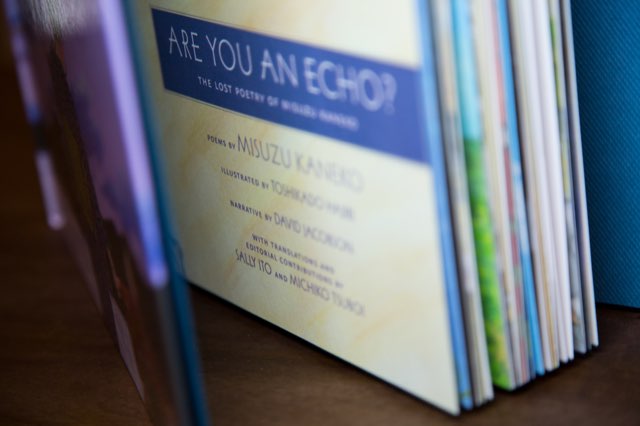

Professional translator Sally Ito just published English translations of the lost poetry of Misuzu Kaneko as part of a children's book called Are You An Echo? But she didn't do it alone. She had the unique opportunity to co-translate with a partner, Michiko Tsuboi.

If you haven't yet read our review of the book, their translations are exceptional. This, combined with our curiosity about the rare co-translation situation, filled our Japanese-learning brains with questions. Thankfully, Sally was happy to answer. For anyone planning on becoming a Japanese translator, or interested in how co-translation works, come learn from Sally's experience.

1. What was your entrance into translation?

My mother is Japanese, and my father a Japanese-Canadian who was completely bilingual, so I was always in a dual language environment growing up. But for literary translation, I really only began doing that when I was in university. I translated Japanese poetry, like the poems of Yosano Akiko and Yagi Jūkichi, and contemporary poet Kazuko Shiraishi.

In 1988 I went to Japan on a Monbusho research scholarship specifically to translate the poetry of Kazuko Shiraishi, whose poems I did eventually publish in some literary magazines.

2. How did you first discover Misuzu Kaneko's poetry?

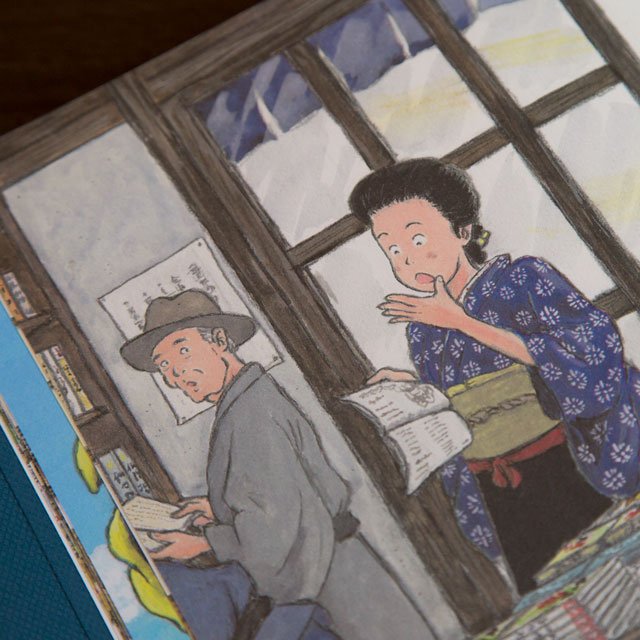

I discovered Misuzu Kaneko's poetry when I was working with the now defunct children's literature blog, PaperTigers. I'd heard about her before I went with my young family to Japan in 2011 and when I was in Japan then, looked for her books. There had been a resurgence of interest in her poetry that year because of the tsunami. Her poem "Are You an Echo?" was aired as a public service announcement during the tsunami crisis.

3. What was the first Misuzu Kaneko poem you read?

I can't remember, but I do remember being struck by hoshi to tampopo 星と蒲公英 or "Stars and Dandelions."

4. What was it about her work that made you want to find more?

She had a way of noticing things people didn't really notice and also exhibited a great empathy for other living creatures, treating them almost as sentient.

5. Who can enjoy Misuzu's poetry?

Everyone that's ever been a child and is not ashamed or embarrassed by entering into that state of mind once again.

6. How did you start collaborating with Michiko Tsuboi?

Well, Michiko is my aunt. She and I had translated my grandfather's (her father's) memoir together as part of research I was doing. After we finished, we wanted to continue working on something else together.

7. What advantages and disadvantages come with a translation partnership?

Michiko and I translated things when we were together in the same geographical place; but of course, now we're apart. I'm in Winnipeg and she is in Shiga, Japan, so we communicate by email and Skype. This is not ideal, but as the work is "textual" in nature, the gap in distance and time can sometimes help us ponder the work and craft it more deliberately. However, having said that, being in the same space with one another would definitely speed up the process of completing more poems than we have been able to do currently.

8. What exactly were your and Michiko's roles?

Our methods evolved over time. At first, Michiko was in charge of selection. She had access to the six volume set of Misuzu's poetry; I did not. So, she basically selected whatever poem caught her fancy and did a first draft translation of it which she would send to me. Then I would read her English to get the basic meaning of the poem, and then I would go to the Japanese and line by line try and reinterpret the poem into more poetic English.

Sometimes, however, I simply could not get things, and we would need to phone each other to discuss the poem. Anyway, I kind of got hooked on the poetry once we started, and I was able to look up Misuzu's poetry in Japanese online on the Misuzu Kaneko museum website. So then when I could do that, I would sometimes initiate the translation of a poem, and then show an English version to Michiko, and she would, in turn, make sure it accurately reflected what was being said in the original.

9. How did you choose which poems to include in the book?

David Jacobson made the selections for the book. David is fluent in Japanese and read all of Misuzu Kaneko's poetry in the six volume set. He decided which poems he wanted for the book. He wanted a representative sampling of Misuzu's poetry to present to an audience completely unfamiliar with her work.

10. Were there any poems you had to cut that you'd like people to seek out and read on their own?

Yes, there were a few. There was a poem addressed to a carp envying the carp flags in the sky, and then there was another poem in which Misuzu chastises humans for being forgetful of people over time (she speaks in the voice of the princess of the moon.)

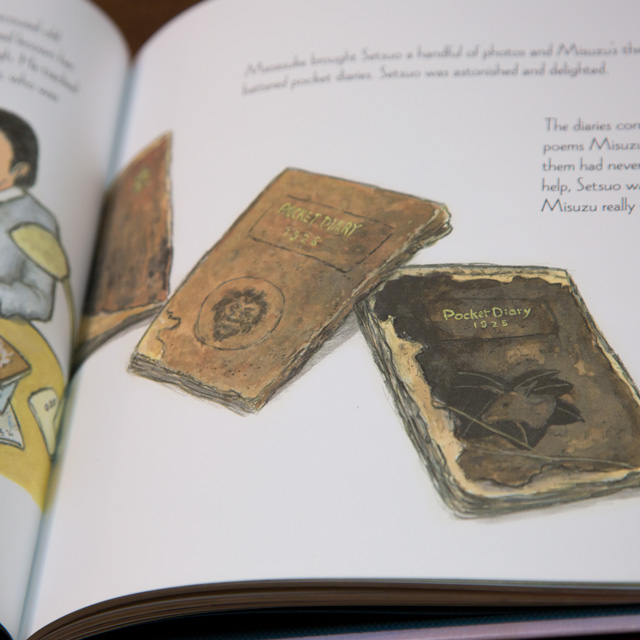

There were others, of course, but there was a certain shape to the book that precluded some poems. Really, the rest of the poetry needs to be translated and published on its own similar to the way it had been initially published after it's rediscovery in 1982.

11. What do you think Misuzu's poems have to teach people outside Japan?

How to be compassionate, empathetic and notice the lives of other creatures, and things, too!

12. How much of Misuzu Kaneko's poetry is there left to translate into English?

As mentioned, only a fraction of the 512 poems in the six volume set have been translated into English, so there is a lot left to do!

13. The book mentions your challenge of preserving the charming, girlish voice Misuzu uses in her poetry. How did you overcome this challenge in the final English translation?

Yes, this was a challenge. The child-like voice can sound "twee" in English, so getting the right tone or tenor of a child's voice in English was tough. I went for a plain-spokenness – people tend to associate children's poetry with rhyming and word-play, but I didn't do that with Misuzu's voice; instead I chose to be as plain-spoken and as direct in my diction as I could be in English to make the poems sound child-like.

14. What are your favorite examples of where you think you found her voice or the proper equivalent particularly well?

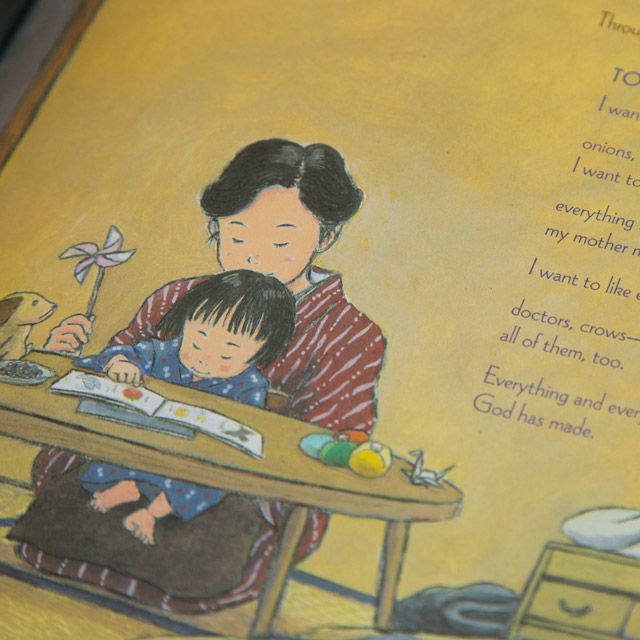

The poem "Mommy Who Walks on the Sea" was told in a child's voice. The child is playing a game of boat-boarding and is calling out to her mother to join her. When her mother doesn't because she's busy, the child makes up an excuse for her absence that is just so delightful and delivered in a tone of voice that is totally a child's. I liked the way we translated this one. I feel similarly about the poem "Treat" as well.

15. Were there any phrases that you had a hard time with? Or any parts where you had to make a decision to "localize" more than "translate"?

We had a lot of interchange over onomatopoeic words like "ko-tsun, ko-tsun" in the translated poem "Dirt." Japanese is an onomatopoeic language and I wanted to leave the onomatopoeic translation of the word alone; however, the editor ended up changing it to an English equivalent.

In "To Like It All", the word kamisama 神様 is used and although the word ‘gods' could have been used, it seemed to me on an intuitive level that ‘God' was the better interpretation. Kamisama can also refer anyway, to the Judeo-Christian God as well and I think that is who the poet is referring to, in this case.

16. Did you ever have the dilemma of wanting to add footnotes to explain something and realizing you couldn't?

No. I don't think we ever thought we were going to use footnotes for any part of this book. The beauty of having an illustrated book is that the illustrations will do a lot for conveying the imagery in the poems.

17. As a poet, and a fan of poetry, are there any other Japanese poets similar (or not!) to Misuzu that you could recommend to our readers?

The other poets I've worked with in Japanese are not children's poets, but I would recommend Yagi Jūkichi and Kazuko Shiraishi. Also, Yazaki Setsuo, who was the literary scholar who rediscovered Misuzu Kaneko's work is also a poet.

18. Would you and Michiko Tsuboi be up for the challenge of translating the rest of Misuzu's poetry together?

Absolutely. We want to translate all the rest of Misuzu's work!