鬼は 外、 福は 内!

Demons out, good fortune in!

You may have heard this phrase, if you've ever participated in, or know about, setsubun (節分). Setsubun is a traditional event in Japan where you attempt to rid your house of evil spirits while welcoming good fortune in. During this event, you say 鬼は外 (demons out) and throw dried soybeans through the window or door towards the soto (outside), then say 福は内 (good fortune in), this time throwing beans towards the uchi (inside).

As this example shows, "uchi" and "soto" (written as 内 and 外 in kanji), are a pair of Japanese words that mean "inside" and "outside." Like other word pairs that describe position or direction, such as "on/off" or "up/down," they help us see different dimensions of things.

内 (Uchi): Inside / In-Group

外 (Soto): Outside / Out-Group

This may sound easy, but I chose to write this article because uchi and soto can be challenging to understand, as they actually go beyond indicating physical position or direction. For instance, they can also be used for social relations where uchi means "in-group" and soto means "out-group."

In Japan, people are constantly making (almost unconscious) decisions about who's uchi and who's soto for them. This is important for Japanese learners to be aware of because the concept of uchi and soto is ingrained in the Japanese language. You may not necessarily hear or use the words uchi and soto much in your daily life, but the ideas surrounding them are reflected in the language.

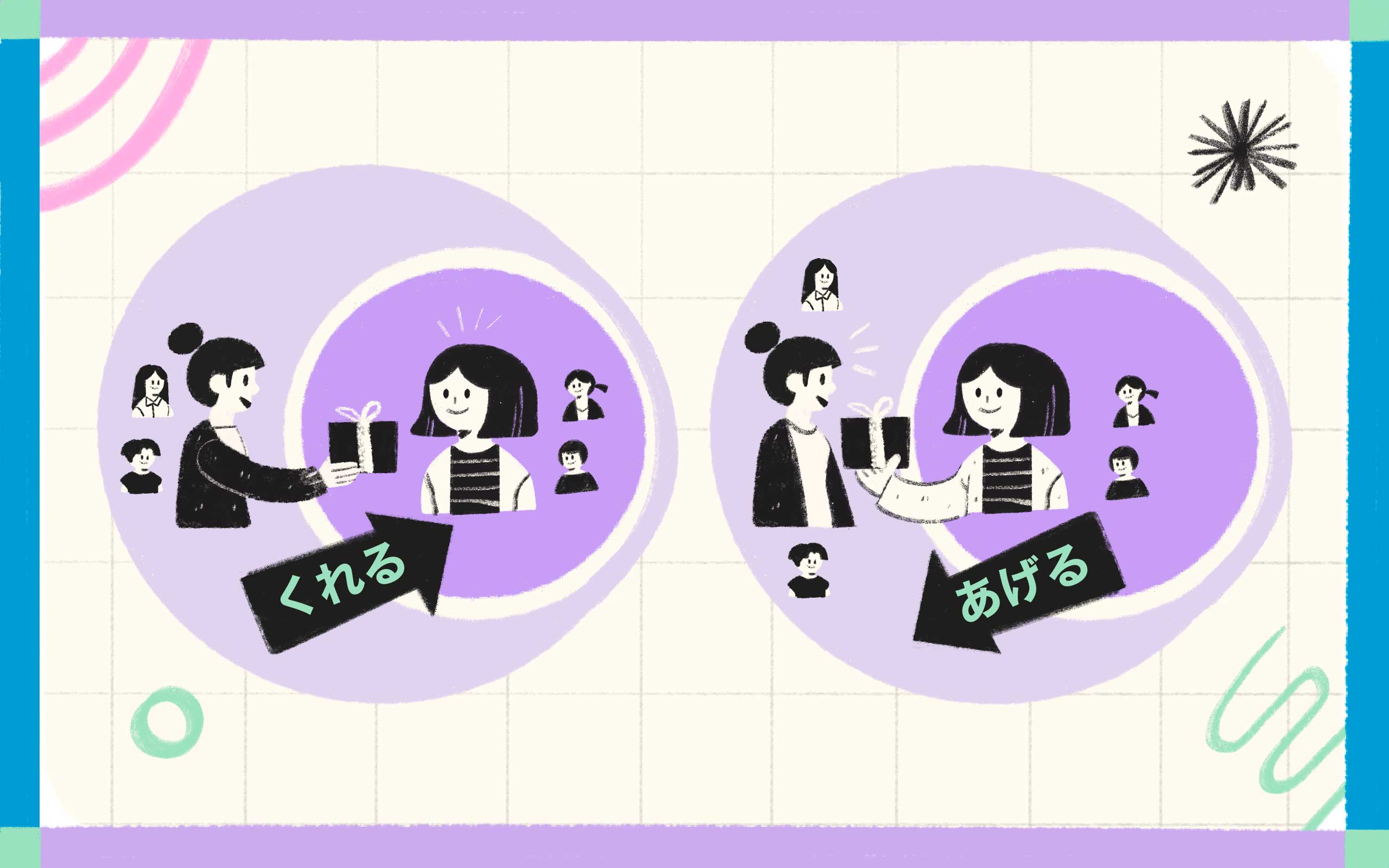

For example, in Japanese, there are two different verbs for "to give" — くれる and あげる. くれる means "to give" from the recipient's point of view, and あげる means "to give" from the giver's, or a third person's, point of view. To decide which point of view to take, you'll first have to judge whether the giver and receiver are in your uchi or your soto. You'll see actual examples later, but I hope this gives you some idea of how knowing about uchi and soto can be crucial for the language.

In this article, I'll walk you through how people decide who's in their uchi and who's in their soto, depending on the situation. Then, later in the article, we'll get into more examples of how uchi and soto are reflected in the Japanese language. By the end of this article, I am hoping you'll come away with a better grasp of uchi and soto!

- Uchi and Soto with Social Relations

- Uchi and Soto Reflected in the Japanese Language

- Keep Learning Until You Know Uchi and Soto "Inside" and "Out"!

Prerequisites: This article assumes you already know hiragana and katakana. If you need to brush up, have a look at our Ultimate Hiragana Guide and Ultimate Katakana Guide. Although we begin with the basic concepts of uchi and soto, you'll get the most out of this if you're already familiar with uchi and soto and have intermediate or higher knowledge of Japanese grammar. This is because we'll be exploring the depth of the two words as well as their application to the Japanese language.

Uchi and Soto with Social Relations

First of all, how do uchi and soto work in social relations?

Besides just meaning "inside," uchi has another core meaning — "home." 1

Home is where the heart is, right? It has associations of security, familiarity, and informality.

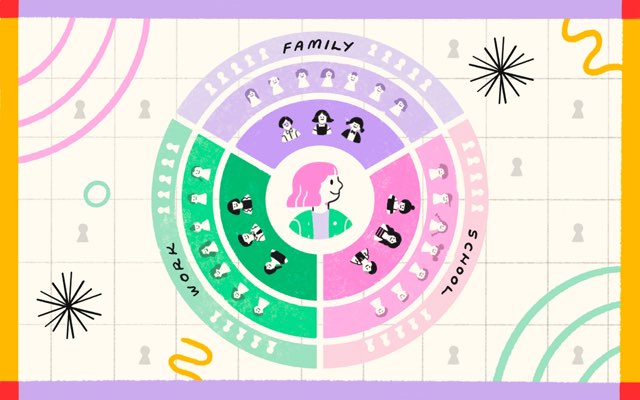

Similarly, uchi can also outline the social circles you belong to. You can think of these circles as your social "home." In each uchi bubble, you are the anchor that fixes you and the people around you in place, and everyone else outside the bubble is arranged in the soto sphere. Needless to say, you are closer to, and more familiar with, the uchi people than the soto people.

The size of each uchi circle and who it includes changes based on the situation. It can be as small as just yourself, or can expand to a family, to a group of friends, to all of your classmates, to an entire school, or to whatever size of a social circle you belong to. This goes all the way up to your country, for example.

Let's say your mom is talking to someone outside the family, like one of the neighbors. She may refer to you as うちの子 ("my kid," literally: uchi's child). In this case, uchi delineates your family and it shows she is talking about you as a member of the uchi (family).

- うちの子は、最近ゲームに夢中なんですよ。

- My kid has been obsessed with video games lately.

You can be referred to as うちの子 by someone outside your family as well. Like when your homeroom teacher, Mr. Tanaka, is talking to someone outside of the class (other teachers, the principal, etc.), the uchi becomes the whole class. So when Mr. Tanaka says うちの子, he's referring to all of his students — you and your classmates in Mr. Tanaka's class.

- うちの子たちは遠足をとても楽しみにしてます。

- Kids in my class (literally: my kids) are so excited about the field trip.

The whole school can be an uchi group too. For example, when the principal is talking to someone outside the school, like a job applicant who's interested in teaching at the school, the uchi becomes the entire school. When the principal says うちの子, they are referring to all students at the school. Depending on what the principal is talking about, the bubble may include the students who have graduated as well.

- うちの子たちは、全体的に英語が得意なんです。

- Kids in my school (literally: my kids) are overall good at English.

So even with the same phrase うちの子, what uchi implies can change depending on who you are, who you're talking to, and what you're talking about.

Now, what if your mom and your homeroom teacher, Mr. Tanaka, were talking? How would they refer to you? Do you think they would both still use うちの子?

For parents, referring to their own child as うちの子 while talking to a teacher is totally normal. This is because a family circle is generally considered to be the uchi-est of uchi circles, at its core. It's natural to talk about a family member as one's uchi to someone outside the family.

- 田中先生、うちの子最近クラスではどうですか?

- Mr. Tanaka, how is my kid doing lately in class?

On the other hand, it's really unlikely that the class teacher would use うちの子 when talking to a students' parent because, in this situation, they are the soto person in relation to the parent.

As you can see from this example, the degree of closeness of relationships within each uchi bubble is different. You may be closer to the people in one bubble than the people in another bubble. When the bubbles overlap, the closer relationship will trump the less close relationship, and it's considered uchi in that context.

The degree of closeness of relationships within each uchi bubble is different. You may be closer to the people in one bubble than the people in another bubble.

As you might have noticed, the uchi and soto relationship is similar to "us" vs "them" in English. In fact, all the うちの子 examples above can be translated into "our child/children," right? Although some argue that uchi and soto are unique to Japanese, that's actually not true. In all societies, we all naturally draw a boundary, tacitly or explicitly, that separates ourselves, or the group we belong to (uchi), from others (soto). The when and how we make those distinctions can vary by culture, and Japanese has its own unique way of doing so.

Now that you have a basic understanding of uchi and soto, we'll explore how they interact with the Japanese language!

Uchi and Soto Reflected in the Japanese Language

In this section, we'll explore uchi and soto concepts that uniquely appear in the Japanese language. First, we'll check out some vocabulary that illustrates uchi and soto relations among people. After that, we'll move on to more indirect uses of uchi and soto, such as keigo and くれる and あげる, which often rely on uchi and soto distinctions without actually referring to them explicitly.

Vocabulary

Alright, let's start talking about the uchi/soto vocabulary!

In Japanese, there are many different words that are associated with the uchi and soto relationship. Although uchi and soto are paired concepts and one always implies the other, not every word has a counterpart. Words using uchi are less likely to have a soto counterpart, probably because people tend to care more about what's near them than what's far from them.

身内 for Your People

身 (somebody) + 内 (uchi)

"One's Family, Relatives, Friends"

Out of all the words that use the uchi/soto concept, a particularly representative word is 身内 (身 "somebody" + 内 "uchi"). The word 身内 refers to people who belong to an uchi group that's very close to the person at its center. So naturally, 身内 indicates one's family and relatives in general. If you have a wedding where you only invite family members, for instance, it's common to use this word and say something like:

- 身内だけの結婚式をあげた。

- We had a wedding with only our close relatives.

As you learned earlier, however, who to include in an uchi bubble is pretty fluid and subjective. So if you feel like you have a family-like, close relationship with someone, you can also call them your 身内. Depending on the context, 身内 in the above example can include your close friends or whomever you consider your 身内.

An expansion of one's 身内 circle is commonly used among yakuza, or gang members, known for their loyalty. They tend to refer to the other members of their same group as 身内. Here is an example from the manga series WORST.

Originalこいつの 兄貴はオレのアニキ分! こいつのダチはオレの 弟分! こいつの女はオレの 妹分! こいつの 親はオレの親! 武装に 関わるすべての身内はオレの身内でもあるんだ!その身内にちょっかい出してただで 済むと思ってんのかコノヤロー! — 河内 鉄生

TranslationThis guy's brother is my brother! His friends are my brothers! His girl is my sister! His parents are my parents! All of the miuchi in the Armament are also my miuchi! Do you think you can get away with messing with them? — Kawachi Tesshō

This quote is spoken by Kawachi Tesshō, the sixth head of a motorcycle gang called the Armament. Here, he included in his 身内 group not only all the members of the Armament but also extended it to all the 身内 (family members, etc.) of the gang members. Kawachi is so deeply attached to the Armament, it doesn't matter if he directly knows the people or not. He says anybody who is related to the Armament is 身内 to him, and he won't hesitate to fight for them. This is his way of stressing how seriously he takes these relationships.

内輪 for an Inner Circle

内 (uchi) + 輪 (ring/circle)

"One's Private Circle"

Another illustrative word for the concept of uchi and soto is 内輪 (内 "uchi" + 輪 "ring/circle"). As its kanji suggest, 内輪 refers to one's private circle that is very close to the person at its center.

This word is actually very similar to 身内 and is sometimes interchangeable. For example, 身内 in the wedding example from earlier can be replaced with 内輪, as in:

- 身内だけの結婚式をあげた。 </br> 内輪だけの結婚式をあげた。

- We had a wedding with only our close relatives.

In this example, however, there is a subtle difference between 身内 and 内輪 in nuance, so what people visualize when hearing each version may be slightly different. That is, while 身内 refers to the people in the uchi circle, 内輪 calls attention to the circle itself and indicates the wedding was done within the bounds of the circle.

As such, 内輪 basically highlights the range of an uchi circle. It's typically used to express the exclusiveness of an event or piece of information, as something only accessible or familiar to those who are inside of the "uchi ring."

身内 and 内輪 can also be switchable in some derivative words. For example, a topic that can be only understood by 身内 (uchi people) in an 内輪 (uchi ring) is called either 身内話 or 内輪話. Similarly, an inside joke can be called either 身内ネタ or 内輪ネタ. However, family or internal trouble is only 内輪もめ and not 身内もめ because the focus is more on the range of the circle where the trouble is occurring.

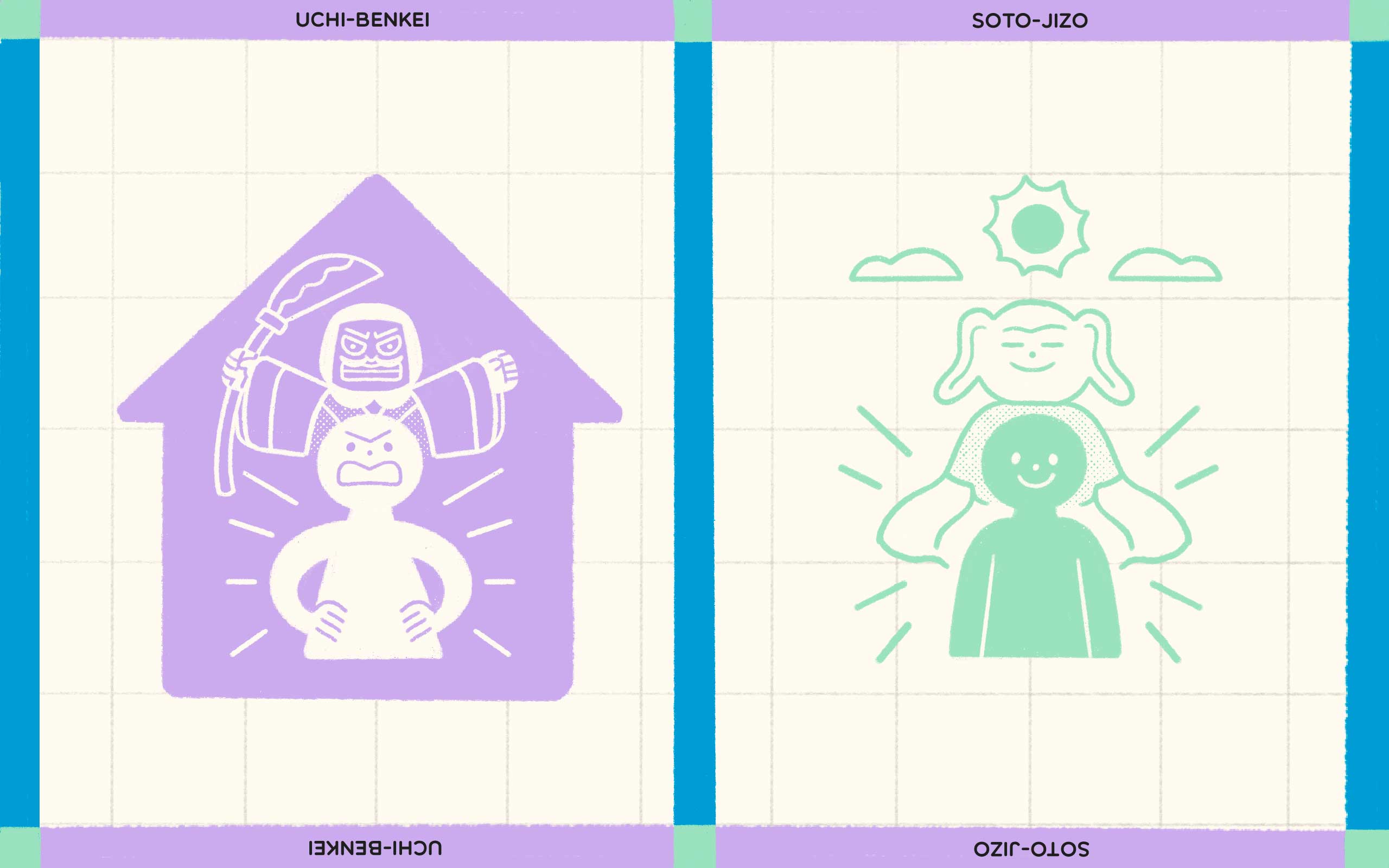

内弁慶 and 外地蔵 (Bossy Inside and Passive Outside)

内 (uchi) + 弁慶 (Benkei)

"Bossy Inside"

外 (soto) + 地蔵 (Jizō)

"Passive Outside"

Next, let's take a look at two paired expressions — 内弁慶 (内 "uchi" + 弁慶 "Benkei") and 外地蔵 (外 "soto" + 地蔵 "jizō"). 弁慶 is the name of an actual historical figure who was known for his strength, while 地蔵 are stone statues of the guardian deity for deceased children, which you can find on Japanese roadsides. So what do they have to do with uchi and soto?

These are just playful ways to depict someone who is bossy in their uchi circle but becomes very passive and submissive elsewhere. Since they only act as strong as 弁慶 in their uchi circle and become as quiet as a 地蔵 statue in their soto circles, they are mocked as 内弁慶の外地蔵. 2

Now, imagine your company president acts controlling with his employees but he becomes shy and meek in front of other people outside the company. In this case, you may refer to the president as 内弁慶の外地蔵, as in:

- うちの社長は内弁慶の外地蔵だ。

- Our president is the bossy-inside, shy-outside type.

In this example, the uchi circle refers to a social bubble encompassing the president's own company, and everyone outside of that is soto. In general, people feel more easygoing in their uchi territory, but 内弁慶 depicts someone who gets too comfortable and acts imperiously.

Also, notice how this example starts with うちの社長 (uchi's company president), which refers to the speaker's company president. From this, we can tell this was said by someone inside the company and it informs others that they work for the unpleasantly inconsistent president.

It's fun to explore uchi and soto vocabulary, but we also have a lot to talk about beyond vocabulary. So let's wrap up this section and move on! In the next section, we'll learn ways to make uchi and soto distinctions without explicitly using each word.

Speech Style and How to Refer to Others

While uchi and soto distinctions exist in all societies, they seem to me to be particularly visible in the Japanese language, at least compared to North American English. In other words, the language you use tends to change depending on if you are talking to people in your uchi or soto.

One good example is keigo. Keigo, which literally means "honorific language," is a formal style of Japanese. As its name suggests, it's used to show your respect to someone. So it's used especially in formal or official settings, but you can find keigo anywhere in daily life.

For example, imagine you are on your way to work in the morning. When you see your friend (your uchi), you can greet them casually, by saying:

- おはよう!

- Good morning!

However, if it's just a stranger (your soto), you'd want to greet them in a more polite way by adding the formal ending, ございます, and say:

- おはようございます。

- Good morning.

As you can see, when you're talking to people in your uchi group, like family members or friends, you usually speak in a casual way. On the other hand, if you are talking to people in your soto group, you are generally expected to use keigo.

The language you use tends to change depending on if you are talking to people in your uchi or soto.

This is because levels of formality can also indicate the distance between people. In general, the higher the formality level, the further the distance, so it makes keigo the natural speech choice for people in your soto group 3. I remember I once made my uncle upset by speaking to him in keigo when I was a kid. My intention was to be polite, but he felt that I was acting unfriendly and distant with him.

As we learned, however, who falls in one's uchi bubble changes based on the situation. The relationships within each bubble vary as well. This means the choice between using keigo or casual language can also shift depending on the context. So, let's say you sent your friend an email yesterday and want to ask if they've seen it yet. In a private conversation, you'd ask them casually, like:

- 昨日送ったメール、もう見た?

- Have you already seen the e-mail I sent you yesterday?

However, if you and your friend work together and this conversation happens in an office with other employees, you may choose a more polite tone, like:

- 昨日送ったメール、もう見ましたか?

- Have you seen the e-mail I sent you yesterday?

This is because an office is a public place (soto) where people usually behave more professionally, instead of making themselves at home (uchi). Although you and your friend speak very casually in a private (uchi) setting, it's common to speak and act in the soto manner in a public (soto) setting.

Similarly, depending on where you are and who you're talking to, you'll also change how you refer to someone by their name or position in Japanese. For example, imagine I'm your friend and you normally call me マミちゃん (my first name with the casual name ender ちゃん). However, if we both work at a traditional Japanese company, Mami-chan is probably considered too friendly. You'd want to switch it to the more polite-sounding 鈴木さん (my family name with an honorific name ender さん), when our colleagues are around.

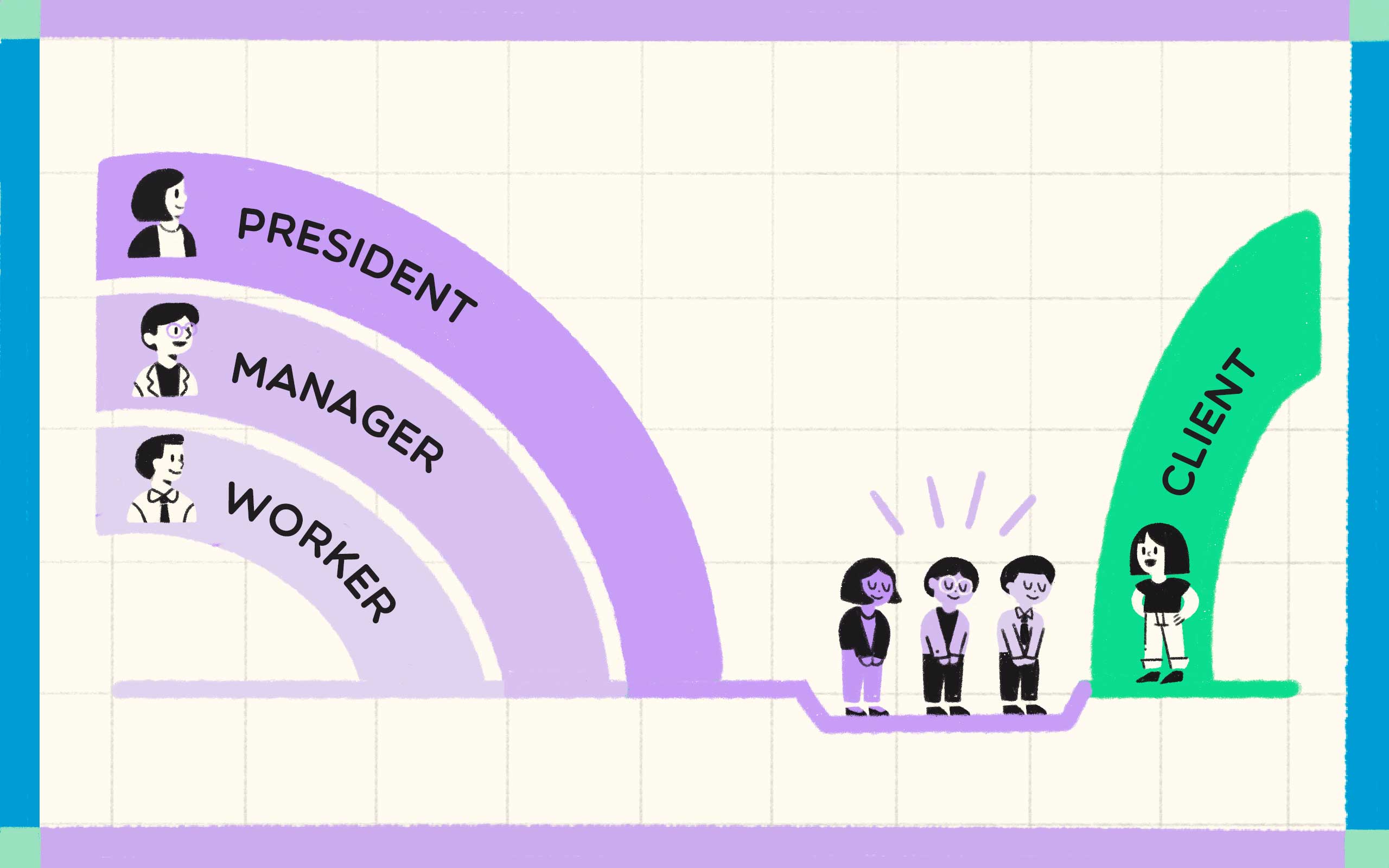

Business settings have another interesting quirk regarding how someone is referred to there. That is, you are supposed to refer to your coworkers in an almost rude way if you are talking with someone outside of your company (soto). And this applies even when you are talking about your superior or company president!

This is because there is a rule of thumb for cross-uchi/soto conversation, which is you raise up the people in your soto while lowering the people in your uchi. When addressing people outside of the company, all workers, from the new intern to the president, will be equal members of the uchi group, regardless of the hierarchy within the company. Pretty interesting, huh?

So let's say you pick up a call from a customer who asks to speak to me. In this case, you are expected to refer to me in a way that isn't respectful because the customer is our soto and you are talking to someone in your uchi. In Japanese, calling someone by their name without a name ender is called 呼び捨て (literally: call and discard). It's often considered rude unless you have an intimate relationship with the person. However, to a customer, you'd use this tactic and call me 鈴木, like:

- 鈴木はただいま外出中です。

- Suzuki is out of the office right now.

Then, as soon as you say that, you notice I'm back in the office. To get my attention, you may shout away from the receiver, and say:

- 鈴木さん、お電話です!

- Ms. Suzuki, there's a phone call for you!

In this case, you are talking to me directly and it's in an office setting where you are supposed to refer to me in a polite way, so you call me by my family name with さん. If I happen to be your manager, you can also call me 鈴木部長 (manager Suzuki) or simply by the title 部長 (manager) because a social role can work as an honorific name ender as well!

This humbling of people in your uchi to honor people in your soto is achieved not only when calling someone by their name or title. There are honorific forms and humble forms for Japanese verbs, and you have to change the form you use according to the situation. This discussion could get pretty deep, so we will save it for another article. Now that you know the foundation of the system, you may show more respect to your soto people, and that will likely also involve lowering your uchi people!

くれる and あげる

Along with speech style, the ideas behind uchi and soto are also blended into some Japanese grammar, such as くれる and あげる. Although you've already seen a basic introduction to these two words, let's take a closer look at them now with some examples.

As a quick refresher, both くれる and あげる mean "to give." To describe the giving action from the recipient's point of view, you'd use くれる, and to describe the action from the giver's point of view, you'd use あげる. And which point of view you choose depends on your uchi and soto relationships with the giver and the receiver.

That is, if the "giving" happens from your soto to uchi (including yourself), you can talk about the situation from the receiver's point of view and use くれる. When the opposite happens, or if you aren't involved with either side, you'll go with あげる.

So let's say your teacher gave you a present. Perhaps it's some extra school supplies they've accumulated that they didn't want to go to waste. In this case, you're the receiver and can use くれる. くれた is the past-tense form of くれる, so after the exchange you'd say:

- 先生がプレゼントをくれた。

- My teacher gave me a present.

And if you give the teacher a bag of potato chips in return, you're the gift giver this time. Here, you'd use あげた, the past form of あげる when saying:

- 先生にポテトチップスをあげた。

- I gave my teacher a bag of potato chips.

Now, what if the teacher also then gives your sister a present? Here, you use くれた again because the giver (your teacher) is your soto and the recipient (your sister) is your uchi.

- 先生が妹にもプレゼントをくれた。

- My teacher gave a present to my sister.

And to show that your sister then gives your teacher a bar of chocolate in return, you'd want to use あげた, the past form of あげる because it's the other way around — your uchi gave it to your soto.

- 妹は先生にチョコレートをあげた。

- My sister gave a bar of chocolate to my teacher.

Are you with me so far? Now, imagine the teacher also gives a gift to your girlfriend. In this case, you can use くれる to describe the exchange:

- 先生が俺の彼女にもプレゼントをくれた。

- The teacher also gave a present to my girlfriend.

By using くれる, you show you are describing the event from the receiver's point of view, and you consider your girlfriend your uchi.

What if you hear the teacher is also giving the gift to your ex-girlfriend? This time, you may want to use あげる to avoid sounding too intimate:

- 先生が俺の元カノにもプレゼントをあげるらしい。

- I heard the teacher's also giving a present to my ex-girlfriend.

By using あげる without being in the teacher's uchi, it indicates you are describing what's happening to your soto. In other words, you can show that you are objectively seeing the event from a third-person position.

If you use くれる, on the other hand, it implies that you still consider your ex to be in your uchi circle, or you still believe you are in a place that is closer to your ex than others. Of course, you can consider your ex as uchi if you still have a close relationship with them, but if you no longer talk to them, or you two are just ordinary (not so close) friends, using くれる after you break up can sound a bit odd (especially if you are in a new relationship).

It's pretty fun to learn how it works, isn't it?

So, why do the Japanese want to distinguish which side you are on? The verb あげる shares the same origin as its homonym 上げる (to raise). It implies offering something to someone who is of higher status than you. In other words, あげる indicates that you are lowering the giver while raising the receiver. Of course, you don't want to lower the giver when you or your uchi is receiving something. Hence, you switch it to a different verb, くれる, to show your appreciation towards them.

You might have noticed, but this perfectly aligns with the rule of thumb of cross-uchi/soto conversation. That is, you are supposed to humble your own uchi people and honor the soto people. So, if you ever get involved in a cross-uchi/soto chat, remember this principle. It'll probably help you figure out what types of speech style or words to select, according to your uchi and soto relations at the time.

Keep Learning Until You Know Uchi and Soto "Inside" and "Out"!

Thank you for reading this article until the very end. The examples introduced here are just the tip of the iceberg. As you continue to learn about the Japanese language and culture, you'll encounter more words, phrases, or customs that reflect the uchi and soto concepts.

Now that you have the basic ideas of how the uchi and soto work in different situations, you can start observing how Japanese people interact with each other, or how the culture connects with uchi and soto, while cultivating your own insights. I hope you enjoy spotting many different uchi and soto relationships from now on!

-

Uchi referring to "home"/"house" alone is usually written in either kana, as in うち, or with a different kanji 家, which means "house." ↩

-

It's also common to refer to someone simply as 内弁慶 or 外地蔵. In this case, however, its counterpart is always implied. ↩

-

Even within a friendly uchi relationship, people sometimes continue to employ keigo due to other factors, such as age. However, people tend to use more friendly keigo rather than very formal phrases in this case. ↩