Kuni can be a troublesome word. Full of ambiguity, it can be translated as country, nation, state, or kingdom. For native English speakers, the confusion is compounded by the distinctions between those words in English, which are not always clear. Some compound words containing kuni (sometimes read koku) also defy clear definition. Some come loaded with historical or political connotations. Here, let's delve into realms etymological, historical, and political in an attempt to better understand a word we may have learned, but not given much thought.

Confounding Kanji

Starting by looking at the kanji for kuni, keep in mind that Chinese characters are somewhat ideographic. This is the original character for kuni, used in Chinese and in Japanese for many centuries:

國

The outer square may look like the character for mouth kuchi 口, but in fact it is a nearly identical character (no longer in common Japanese usage) meaning "erect," "proud," or "upright." In print or type they look indistinguishable to me, though when written with a brush there is a subtle difference.

Aside from the character's standalone definition, it is often used to enclose other radicals, sometimes words whose meanings are connected to a concept of walls, borders, or enclosures: for example, garden niwa 園, arrest shuu 囚, and surround i 囲. Of course if we're talking about kuni as a country or state, then those things have borders.

Inside the outer square is the character 或. It can mean: 1. or, either, else; 2. perhaps, maybe; 3. someone, somebody, some people. I'm not sure how much bearing the first two definitions have on the meaning of kuni, but the third makes sense. A kuni can be seen as some people enclosed within borders, although of course that would be a pretty broad definition.

However, a different character is used for kuni in modern Japanese:

国

There's the same outer enclosure, but inside is the character tama 玉. This character's most explicit meanings are jade, jewel or ball, though it is used in many ways to refer to things that are round, shiny, and/or pretty. However, in some contexts, it can represent the emperor or king. The usual character for king, o 王, is quite similar, and jade was often symbolic of royalty in China. One Japanese example that shows their parallels is the traditional chess-like game of shogi, where the king equivalents for each side are labeled Ōshō 王将 "king general" and Gyokushō 玉将 "jade general," respectively. At any rate, it's easy to see how in pre-modern East Asia a country could be seen as a king and his borders.

English Etymology Excursus

Before delving further into the origins and meanings of kuni I think it best to take a look at the deeper meanings of some of its most common English translations. The common usage of these words may not always get across the more precise meanings of these (especially the meanings they imply to historians). I think the most relevant words for us to look at are country, nation, state, and nation-state.

In English, the word country usually refers to a region of land defined by geographical features or political boundaries. Today "country" is often synonymous with a sovereign state. A state is the set of governing and supportive institutions that have sovereignty over a definite territory and population. Still, there are cases, such as those of England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, where an area that is not a sovereign state is called a country. Of course country can also refer to the country(side) or a general sort of native land.

A nation denotes a people who are believed to or deemed to share common customs, religion, language, origins, ancestry or history. The term nation-state is used when the bounds of a government coincide with the range of the people it governs, who share some of the qualities mentioned above. Some states could also be labeled multinational, though the distinctions of what constitutes particular nations can be unclear sometimes. The prevailing scholarly view has been that nations are a product of modernity that began to emerge around late 18th century and have really taken off since. However, some argue that there are older examples. Among the various views on the matter, there are some that put forward the idea that China, Korea, and Japan were nations by the time of the European Middle Ages.

Straight to the Sino-Source

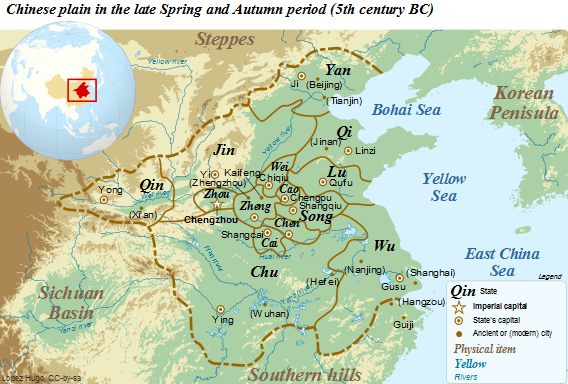

Many people have heard China called "the Middle Kingdom," a translation of the word for China, zhongguo 中國. However, originally zhongguo referred to multiple "central states," during the Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BCE) and the aptly named Warring States period (475-221 BCE). These were originally smaller city-states, but expanded and fought until the leader of the state of Qin finally managed, through conquest, to unify these former states under his rule. It is from Qin, that we get the English name China. From China's history we can see that guo could be just as multifaceted a term for them as kuni was for Japan.

Conflicting kuni Connotations

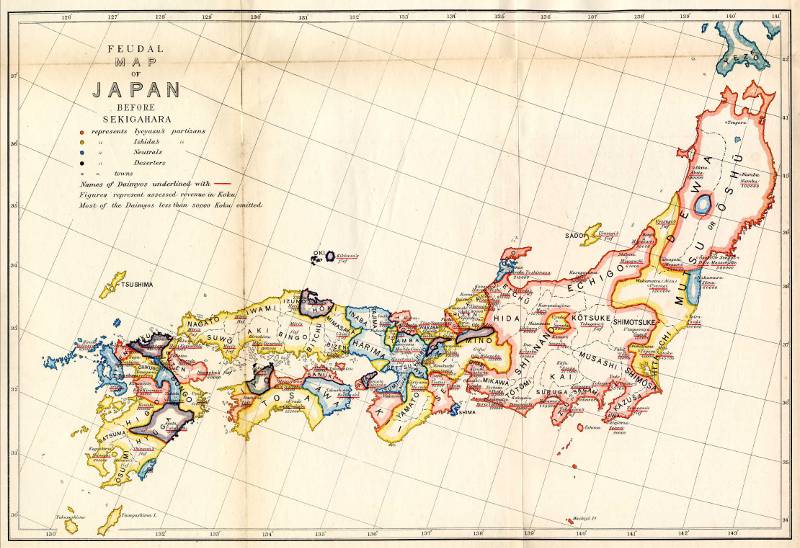

Things get even trickier when looking at the Japanese era from 1467 to 1603 known as the Sengoku period (sengoku jidai). It was a time when both emperor and shogun had lost authority and regional lords vied with one another to defend and expand their territories. The tricky part is that the term used for these lords' territories was kuni. This was a designation that originated from legal system of the Kamakura period (1185-1333). In that sense, kuni could be thought of as provinces, but by the Sengoku period they were largely operating as sovereign states. Thus, Japan, which we call a kuni today, was made up of many largely independent kuni.

I did a little informal polling of some of my Japanese friends to see how they interpreted the term "sengoku jidai." Interestingly, two told me that the image they associated with those words was of a single kuni (Japan) divided by civil war, but two other friends told me that to them it connoted the idea of many smaller kuni fighting one another. It would seem that the term is vague even for them, but without much consequence for the average person. As another friend told me, they didn't cover the Sengoku period much in school, but if pressed the first impression would be an association with the Sengoku Musou video games.

At any rate, I think interpreting the kuni in Sengoku period as referring to the smaller divisions accords better with history. There was a sense of the traditional authority of the emperor, but during this period that authority was extremely limited. For the most part, kuni were their own little sovereign states. There appears to have been some sense of bond from sharing a common language, and many common traditions, but there was also great cultural diversity, and a Japanese nationality would not be fully realized for some time to come.

Dissecting the National Body

There are many compound words that include the charater kuni, and kokutai 国体 is another one with ambiguous meanings. kokutai literally means "national body," but depending on the context and the translator can have meanings such as "system of government," "sovereignty," "national identity/essence/character," and "national polity/body politic/national entity." The word has its origin in China, where its first known usages are found in two books from the 2nd century BCE and 1st century CE, respectively. In the former, the word is used as a metaphor meaning the "embodiment of the country," while the latter tome uses it to mean "laws and governance."

The word kokutai began to take on importance in Japan during the Tokugawa period (1603-1868), due to Neo-Confucian scholars like Aizawa Seishisai (1782-1863), who popularized it in his 1825 book, Shinron. Seishisai was head of the Mito School, which supported restoring the emperor to power. Seishisai idealized imperial rule as a perfect unity of religion and government. In his work, kokutai is vague, but seems to mean something like "national structure."

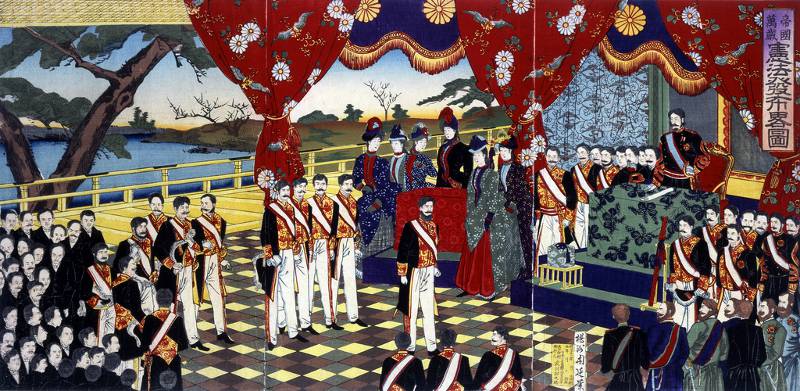

During the Meiji period, after the nominal restoration of imperial power, ideas of kokutai developed and diverged. Kato Hiroyuki (1836-1916), in his kokutai shinron, drew a distinction between kokutai 国体 and seitai 政体. To him, kokutai was the national essence of Japan, made of eternal elements drawn from tradition and focused on the emperor. On the other hand, seitai was the form of the government which had changed over time. Thus, it was okay to adopt a western form of government, as long as the emperor was there the kokutai would remain unchanged.

Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901) took a different approach to kokutai, and believed it was not a uniquely Japanese phenomenon. He thought every nation had its own kokutai, and that Japan's did not depend on the purported divine descent of the emperor. When the Meiji Constitution was created in 1889, it accorded more with Kato's views.

Throughout the subsequent Taisho era Japan grew more nationalistic and militaristic, and the notion of kokutai took on more and more of a mystical aura revolving around the emperor. This continued into the Showa period, when a committee of professors was appointed to better define kokutai. In 1937, they issued kokutai no Hongi ("Cardinal Principles of the National Body"), which taught that everyone was part of the state. The principles in this pamphlet were spread throughout the education system and society, and both the word kokutai and its spirit were widely featured in propaganda. Following World War II, the Allied General Headquarters prohibited circulation of kokutai no Hongi, and the importance of kokutai faded, though some argue that traces of it are still evident in Japanese society.

What's in a Name?

All of this analysis of a single character may seem a bit esoteric or even pointless. While I won't be shutting myself away to meditate upon the mysteries of the word kuni for the rest of my days, I do think it's beneficial to reflect upon the words we use sometimes. Particularly for those who study history, the distinction between nation, state, and country can be important in many instances. When one reads in Japanese, the vagaries of translation and of the Japanese language itself add another step or two on the path to understanding, another chance to misstep. The better we understand the words we use, the less chance there is of falling. There's a lot more nuance to kuni and its English translations than I was able to touch on here, so I encourage you to check it out.