Table of Contents

The Basics

Putting a verb into the ている form indicates that we're talking about an ongoing situation that started in the past. We like to think of it as expressing a sort of "activation mode".

Many verbs in the ている form express continuous actions, such as 食べている (to be eating), 勉強している (to be studying) and 雨が降っている (to be raining).

However, some verbs in the ている form express the result of an action. For example, one of the meanings of つく is "to turn on," and the ている form of this, ついている, means "to be on" rather than "to be turning on." Similarly, the verb やせる means "to lose weight" and its ている form, やせている, means "to be slim," not "to be losing weight."

Conjugating Verbs to Make Them into 〜ている

To make a verb into the ている form, conjugate the verb into the て form and add 〜いる to the end.

The ている form of a verb can then be conjugated like other ichidan verbs. Here are a few basic conjugations of 〜ている.

| Present | 〜ている |

| Present (Polite) | 〜ています |

| Past | 〜ていた |

| Past (Polite) | 〜ていました |

| Negative | 〜ていない |

| Negative (Polite) | 〜ていません |

| Past Negative | 〜ていなかった |

| Past Negative (Polite) | 〜ていませんでした |

We should also point out that 〜ている usually becomes 〜てる in casual situations. You'll see this ending in some of our example sentences — don't make a rash judgment and report us to the grammar police. 😉

Conceptualizing 〜ている

As mentioned before, a verb in the ている form describes an ongoing situation that started in the past. In other words, the ている form is telling you "this is what's going on now, and that's because the action or state was turned on or activated in the past."

Imagine a robot that's programmed to eat food when it's powered on. When you turn on the "eat" switch, the robot starts the "eating" process. This "eating mode" is described with 〜ている, as in:

- (私は)昼ごはんを食べている。

- I am eating lunch.

With dynamic verbs like this, 〜ている often works in a similar way to the present continuous in English. That is, it shows that an action is progressive or continuous, meaning it's happening at the same time as it's being spoken about.

Other types of verbs produce a different effect when paired with 〜ている. For example, the verb つく means "to turn on", but in the ている form, it means "to be on" rather than it "becoming" on:

- テレビがついている。

- The TV is on.

We'll look at how the exact meaning changes according to the verb and the context later, but the underlying meaning of ている is always "this is the situation now, and that's because it started in the past."

Now, let's start by taking a look at more examples of 〜ている used for continuous actions!

Uses

〜ている for Continous Actions

The most basic use of 〜ている is when it shows that a verb is progressive. This includes all sorts of ongoing activities that started at some point in the past. It covers both activities that are happening temporarily right now (similar to the "present continuous" or "present progressive" in English), and actions that have been continuously happening up to the present (similar to the "present perfect continuous" or "present perfect progressive" in English). It can also be used for habits and other things that happen frequently.

〜ている for What's Happening Now

You can use 〜ている to describe something that's happening at the time you are speaking, like we use "to be -ing" in English. For example:

- お父さんはリビングでテレビを観ている。

- Dad is watching TV in the living room.

This basically means your dad's "TV-watching mode" has been activated.

Now imagine the TV stops working, and your dad starts hitting it in the hope of fixing it:

- お父さんはテレビを叩いている。

- Dad is hitting the TV.

In this case, the action of 叩く (hit) is instantaneous and ends right away, but because it's repeated, your dad is in a "hitting mode" and that ongoing state is described as テレビを叩いている.

Unfortunately, by hitting the TV, your dad unsettled a cloud of dust, and he starts sneezing:

- お父さんはくしゃみをしている。

- Dad is sneezing.

Just like in the previous example, sneezing is usually an instantaneous action. However, because it's repeated, you can consider that his "sneezing mode" has been activated. Using 〜ている shows that it's a repeated action, not a one-off.

What if he does a very long, magnificent sneeze? Like, "achooooooooooooooo!!!!!" In this case, even though it's one action, it's long enough to say that your dad is in "sneeze" mode. It's not a common situation, but it is possible to use 〜ている and say:

- お父さんはとても長いくしゃみをしている。

- My dad is having a very long sneeze.

I wonder how long his sneeze lasted.

Now let's say you're having a party, so there are many people in the room when your dad hits the TV. The dust causes everyone to sneeze, so you say:

- みんながくしゃみをしている。

- Everybody is sneezing.

In this case, 〜ている shows that many people are repeating the action of sneezing. Everybody is in this "activation mode."

〜ている for What's Been Happening

You can also use 〜ている to describe something that's been continuously happening up until the time you're talking. This is like "to have been -ing" (the present perfect continuous) in English. For example:

- 去年から日本語を勉強している。

- I've been studying Japanese since last year.

Here, ている shows that you activated your Japanese studying mode last year, and you've been in that situation up to the present moment.

The activated situation doesn't have to be a long period of time. For example, if you're talking to your friend but they look spaced out, you can ask:

- ねえ、私の話、ちゃんと聞いてる?

- Hey, are you listening to my story?

Hey, have you been listening to my story?

With this example, both "to be -ing" and "to have been -ing" work in English. Regardless of the translation you choose, you're asking if your friend is or has been in "listening" mode, because, to you, your friend's "listening" switch doesn't seem properly turned on.

〜ている for Habits and Frequent Occurrences

We also use the ている form for habits or recurring events. It describes what you are doing in general, not just in this particular moment. Going back to our sneezing dad, imagine that he picks up an allergy from all that dust and his sneezing and coughing goes on for months:

- お父さんはいつもくしゃみと咳をしています。

- Dad is always sneezing and coughing.

Just like in English, the word いつも (always) tells that this is a habit, rather than something that's only happening right now. Context is very helpful in telling us exactly what we should understand from a verb in the ている form.

Similarly, if you recently got into a natto phase and you've been eating natto often, you can say:

- 最近よく納豆を食べている。

- I've been eating natto a lot lately.

In this example, 〜ている is the perfect choice to show you're in a natto phase.

However, if you remove the words 最近 (lately) and よく (frequently) and just say 納豆を食べている, it sounds like the present continuous (I'm eating natto). Again, to determine the meaning of 〜ている, you'll need to pay attention to extra context like this.

Now, let's say you're not just in a phase, but actually have a well-established habit of eating natto every morning. In this case, you can use either the plain form or the ている form of the verb 食べる (to eat).

- 毎朝納豆を食べる。

毎朝納豆を食べている。 - I eat natto every morning.

While the plain form of 食べる sounds like you're simply stating a general habit, like listing it as a bullet point item, 食べている adds the nuance that you're doing it proactively. It's a continuous situation that you yourself "activated" willingly.

住む with 〜ている

Some verbs are viewed a bit differently in Japanese, compared to English. Because of this, you might see 〜ている used in situations where it wouldn't be used in English. Let's take a look at an example:

- 私は東京に住んでいる。

- I live in Tokyo.

住んでいる is the ている form of 住む, which is equivalent to the English verb "to live." In English, we usually say "I live in…" instead of "I am living in…" unless we want to stress that it is a temporary living situation. That's because in English we usually consider the verb "to live" to describe a state rather than a dynamic action.

These kinds of verbs, called "stative verbs" are sometimes used in the present continuous form in English when you want to emphasize the temporary nature of the situation. However, in Japanese, no matter whether it's a temporary situation or not, we use 住んでいる for current (and sometimes future) living situations because the action is continuously happening.

〜ている for Resulting States

Remember how 〜ている indicates an ongoing situation that was activated in the past? In the last section, we looked at verbs that describe actions that don't involve immediate change. With those verbs, the ている form describes the ongoing action.

In this section, we'll look at what happens when the ている form is used with verbs that change the state of something instantaneously. With these verbs, the ている form describes the state that results from the change.

Let's look more closely at one of the examples from earlier:

- テレビがついている。

- The TV is on.

テレビがつく (the TV turns on) normally happens in the blink of an eye. It changes the status of the TV instantly from "off" to "on." ついている, the ている form of つく, is used to describe this "on" state, which was activated when テレビがつく happened.

So, when a verb changes the state of something instantly, the ている form of that verb describes the resulting state. The clue to whether a verb falls into this category or not is if the change is instantaneous.

To understand this use of 〜ている, let's check out a few more examples. When a living thing dies (死ぬ), it immediately changes from "alive" to "dead." In other words, the state of "being dead," is an activated state in Japanese and it is described as 死んでいる.

So, if you saw a dead bug on the street, you could say:

- あ、虫が死んでいる。

- Ah, the bug is dead.

This doesn't mean the bug is dying. It means the bug is dead. Just like the TV on/off example, the "death" switch of the bug was flicked and the bug is in the state of being dead, so we use 〜ている to explain that state.

You might now be wondering how you'd say the bug "is dying"? For this, you'd first change 死ぬ into its かける form. かける means "half-done" or "not yet finished," so 死にかける is something like "to be half-dead." You'd add 〜ている to indicate that the bug's almost dead mode has been activated:

- あ、虫が死にかけている。

- Ah, the bug is dying.

Verbs ending in かける don't describe an instant change, so they fall into the same category as verbs like 食べる which we talked about earlier.

It's a bit complicated, isn't it? It's a different system from English, so it's totally normal to take time to digest it. You'll get it eventually though.

Let's look at another example. Imagine you are walking down the street and you come across a wallet on the ground. In this case, you use 落ちる (to fall):

- あ、財布が落ちている。

- Oh, there's a wallet on the ground.

When the wallet fell on the ground, the status of the wallet changed to "fallen wallet." It's the result of the action of falling, so it's described with the ている form. 落ちている indicates that the wallet has fallen on the ground and is now in that state.

We can add かける to this verb too. 落ちかけている describes a wallet that is just about to fall, like when it's sticking out of someone's pocket.

And what if you want to describe the wallet actually falling? In this case, you'd say 落ちてくる or 落ちていく, depending on your position in relation to the wallet. And you could even turn them into their ている forms, as in 落ちてきている and 落ちていっている, if you wanted to emphasize that the actions are taking time to occur.

Let's take a look at one last verb that works like this. The verb 疲れる means "to get tired." As you can guess, to say someone is tired, you use its ている form. So if you worked until late last night and you are very tired today, you can say:

- 今日はとても疲れている。

- I'm very tired today.

Here, 〜ている suggests you are in the activated state of "being tired." If you want to emphasize the change of getting tired rather than your current state of being tired, you could use the た form of the verb instead. For example, if you've just finished a lot of work and you suddenly feel tired, you'd say:

- あー、疲れた!

- Ah, I'm tired.

In this case, the closest English translation is "I'm tired" but what it really means is "Ah, that tired me out!"

もう and まだ with ている

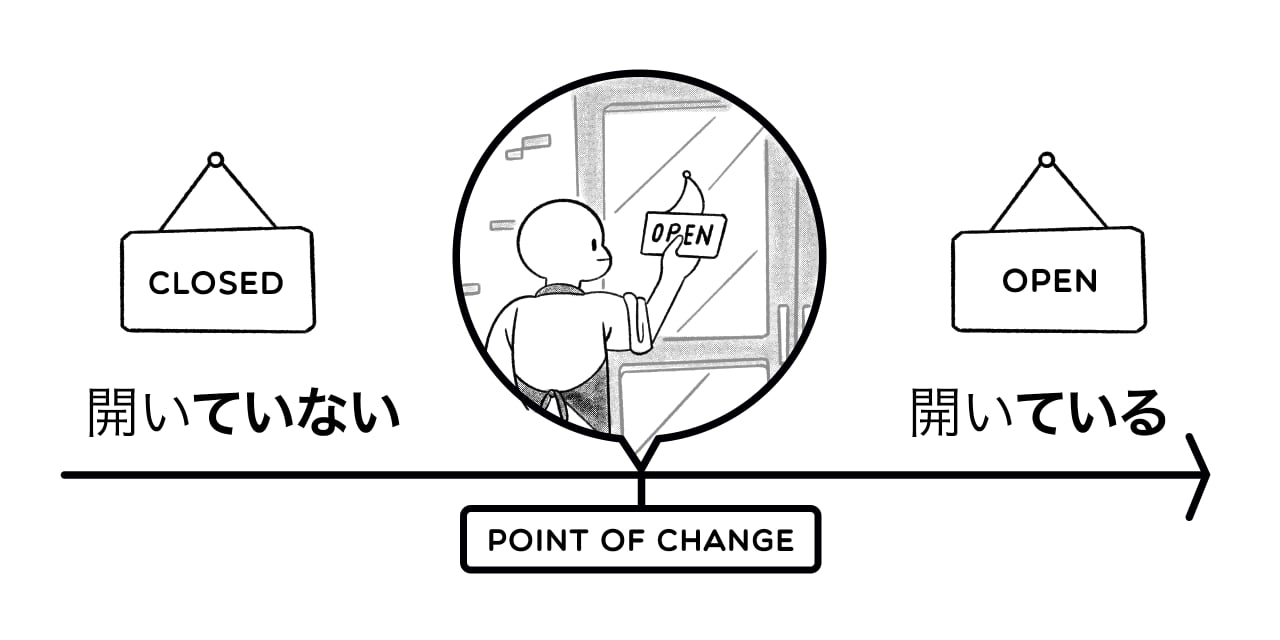

So now you know that 〜ている can be used to describe the result of a change. This also applies to situations in English when we want to say we "have already done" (もう) something and "have yet to do" (まだ) something. Imagine you and your friend are searching online for a place to meet for a morning coffee. It's 4 a.m., so most coffee shops haven't opened yet, but you find one that's already open. In this case, you'd use 〜ている and say:

- このカフェはもう開いている。

- This coffee shop is already open.

A coffee shop that is open at 4 a.m. — wow! You can use 〜ている because the coffee shop is in the state of "being open" which was activated by the change of someone opening it.

When you describe the state before a change, you can use the negative form of 〜ている and say:

- このカフェはまだ開いていない。

- This coffee shop isn't open yet.

Easy peasy, right? So, when wouldn't we use this form? Take a look at this example:

- そのカフェはまだ開かない。

- The coffee shop still won't open.

This example simply uses the negative form of the verb 開く (to open), instead of 〜ていない. Since this one focuses on the change from the coffee shop "getting opened," it sounds like the coffee shop won't open anytime soon. On the other hand, the previous example that used 〜ていない describes the current state of not having been opened yet, and implies it might open soon.

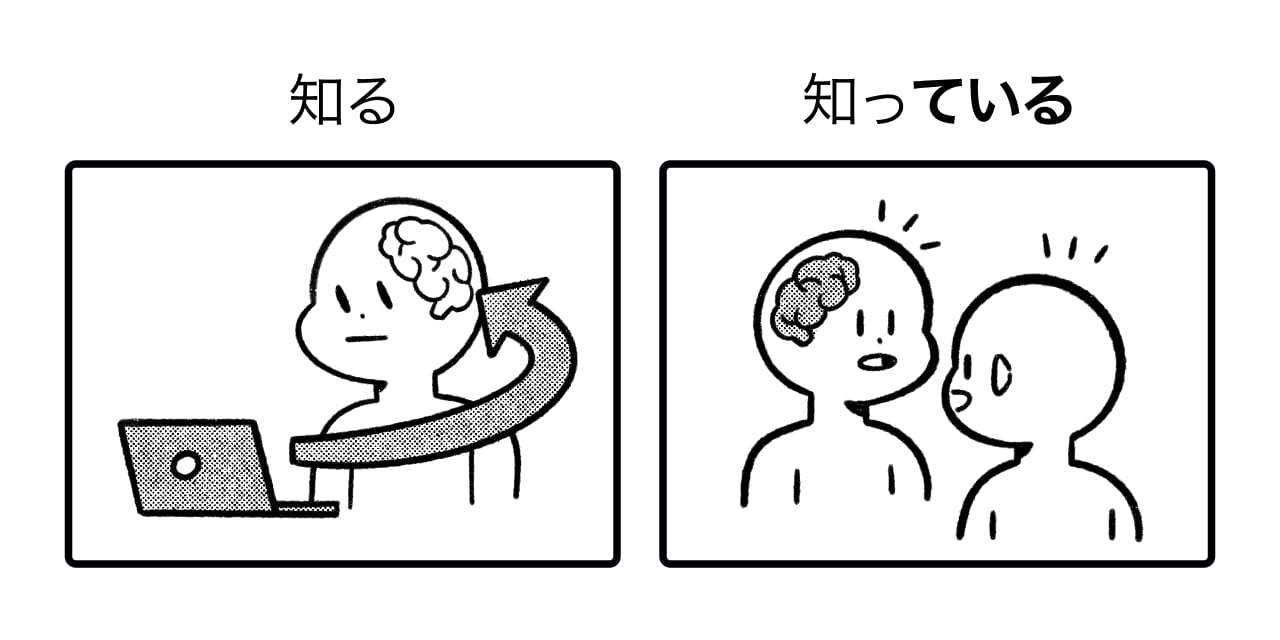

知る with 〜ている

The Japanese verb 知る is often translated as "to know," but technically a more accurate translation would be "to get to know something" because what 知る actually means is the change in the state from "not knowing" to "knowing." When the piece of information enters your brain, that's 知る.

So what about when you have the information stored in your brain and simply want to say "I know something"? That's when we use 〜ている.

Let's say your friend asks you if you know that 〜ている can be used for things like "I live in Tokyo." You'd say:

- ああ、知っている。

- Oh yeah, I know.

Because you already learned it (like a minute ago), you deserve to say you already know it. Notice that the example is using 〜ている here. This is because the status of your knowledge has changed from "not knowing" to "knowing."

If your friend asked you how you learned about it, you'd say something like:

- トーフグというウェブサイトで、知った。

- I learned about it on the Tofugu website. (Literally: I got to know that on a website called Tofugu.)

You use the past tense of 知る here because you're describing the change from "not knowing" to "knowing."

A similar example of this is 分かる (to understand). 分かる focuses on the change of state from "not understanding" to "understanding," but 分かっている describes the state of you already understanding.

Beyond the Basics

いる and ある with 〜ている

To say someone or something exists in Japanese, as in "there is someone/something," you can use two different verbs, いる and ある. In general, いる is used when you expect movement, and ある is used when you don't.

Verbs that express states don't take 〜ている. Since existence is a state of being, いる and ある don't generally take 〜ている either.

ある is nice and simple: it never takes 〜ている. This is because ある never indicates a dynamic action. It's only used to describe existence.

- ⭕ 私の実家は東京にある。

❌ 私の実家は東京にあっている。 - My parents' house is in Tokyo.

In the same way, the verb いる doesn't normally take 〜ている either.

However, some dialects, such as the Kansai dialect, use いてる to describe existence for a temporary period, like "I'll be at home for an hour or so" or "I'll be at a cafe while waiting for you."

- Kanto dialect: 待ってる間、あそこのカフェにいるよ!

Kansai dialect: 待ってる間、あそこのカフェにいてるわ! - I'll be at that cafe while waiting for you.

Speakers of the Kansai dialect perceive temporary existence at a certain location as an activated state you have control over. In other words, you can decide to be there or not. So it takes 〜ている. On the other hand, speakers of the Kanto dialect, a.k.a. standard Japanese, don't distinguish between temporary existence and general existence, so they use いる, and not いてる.

Transitivity and 〜ている for Resulting States

When 〜ている is used for states that result from the verb, the nuance can be a bit different depending on whether the verb is intransitive or transitive.

Take, for example, つく and つける, a transitivity pair. つく is the intransitive half of the pair:

- テレビがついた.

- The TV turned on.

In this sentence, neither how nor why it happened is explained and it sounds like the TV turned on by itself.

On the other hand, つける is transitive:

- (私が)テレビをつけた.

- I turned on the TV.

This sentence shows that the subject, I, transfers energy to the TV, causing it to come on. It involves one entity acting upon another.

Now, let's put these verbs into the ている form.

- テレビがついている。

- The TV is on.

Yes, this is the exact same sentence we used earlier. To refresh your memory, an instantaneous action like turning on the TV activates the TV's new state of being on. That activated state is expressed by 〜ている.

When the verb is intransitive, it expresses that the TV is on, without mentioning how or why it's on, so it has a neutral feel.

When the verb is transitive, however, it conveys the nuance that someone turned it on deliberately. That person put in the effort of transferring energy to the object to cause the state.

- (私が)テレビをつけている。

- I have the TV on.

So in this sentence, つけている adds the nuance that you have the TV on intentionally, and you probably have a specific reason to have it on. Maybe you're waiting for your favorite TV show to start!

When 〜ている Can Be Interpreted Two Ways

We saw earlier that instantaneous verbs generally express a resulting state when they're in the ている form, but in certain situations, it's also possible to interpret the meaning as a repeating event. This is generally only possible when the subject is plural.

Let's have a look at what we mean by going back to the verb 死ぬ (to die). Remember how 死んでいる is almost always interpreted as "dead" rather than "dying"? So if you are talking about the tragedy of war, which has caused the deaths of many soldiers, you can say:

- この戦争では、多くの戦士が死んでいる。

- Many soldiers are dead as a result of this war.

And if you mentioned the same thing when the war was still happening, it could also mean:

- この戦争では、多くの戦士が死んでいる。

- In this war, many soldiers have died.

Although the English translations are different, both examples are talking about the state resulting from the war.

However, depending on the context, this can also mean:

- この戦争では、多くの戦士が死んでいる。

- In this war, many soldiers are dying.

In this example, you are describing the situation as multiple repeated events. This is like the earlier example of many people sneezing. In that example, the different people's sneezes were events that kept on repeating.

In the same way, if you come across a breathtaking sight of beautiful leaves on the ground, you may say:

- うわぁ、葉っぱがたくさん落ちている。

- Wow, tons of leaves are on the ground.

Yet, since this sentence has a plural subject, tons of leaves, 落ちている can also indicate the progressive state in terms of the iterations of the falling events across multiple leaves. So the exact same sentence can also be used to describe many leaves falling off of a tree, as in:

- うわぁ、葉っぱがたくさん落ちている。

- Wow, tons of leaves are falling.

Again, the intended meaning is generally clear from the context. If it's ambiguous, there's often a more precise verb that you can use to avoid confusion. For example, in the case of falling leaves, it's more common to use the verb 舞い落ちる (to flutter down):

- うわぁ、葉っぱがたくさん舞い落ちている。

- Wow, tons of leaves are fluttering down.

You can also use 〜ていく or 〜てくる endings to add direction, such as 落ちていく (to be falling down away from me) or 落ちてくる (to be falling down towards me), to clarify you are talking about the falling action of the leaf rather than the state as the result of falling.