Table of Contents

The Basics

The particle は is attached after a word (or a group of words) to show that it is the "topic" of the phrase, sentence, or paragraph. A topic is the theme of the conversation, and is always something that the speaker believes to be in the listener's consciousness, or believes that the listener can identify.

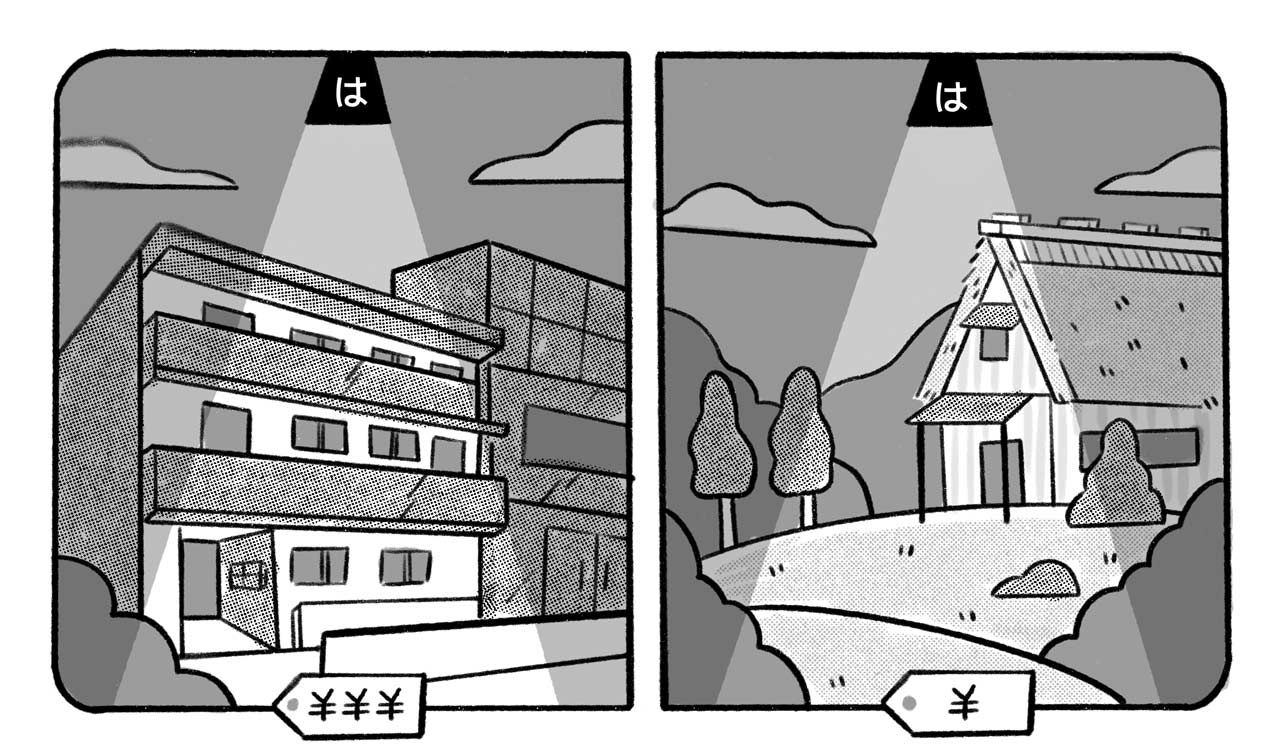

In fact, は is like a spotlight, shining on the topic and leaving other potential topics in the dark. This is because は creates a nuance of contrast between the topic it picks out and other potential topics, which are left in the shadows, whether those other topics are mentioned or not.

は as a Topic Marker

In its most basic use, the particle は goes after a noun, or a group of words that works like a noun (a noun phrase) to show that this noun is the topic. It shines a spotlight on that noun, and tells us that it is the theme of our discourse. In terms of meaning, は is the rough equivalent of "as for" in English, but は is used far more frequently than "as for."

Because the topic is always something that is supposed to be already in the listener's consciousness, the emphasis is on the information about the topic — which is the new information — rather than that topic itself.

For example, in the sentence below, 日本語 (Japanese) is something the listener is already aware of, but the fact that it's 面白い (interesting) is considered to be the new information, or the information we want to focus on:

- 日本語はおもしろい。

- Japanese is interesting.

(Literally: As for Japanese, it's interesting.)

This is a pretty special feature of Japanese, as there are very few languages in the world that have a specific grammatical way to pick out a topic. Since most languages don't indicate topics directly, it can be hard for the rest of us to pin down exactly what the concept of topic involves. Let's have a look at some examples to make this concept more concrete.

- これは何ですか。

- What's this?

In this example, これ (this) is the topic. If someone says this to us, we would already know what これ refers to from the context. Maybe the person speaking is pointing to an object, making it clear that it's what they're talking about, or maybe they're holding something up to show you as they speak. Somehow or other, you should know what これ is from context, just as you would if someone said "What's this?" in English.

What about this next sentence? Can you spot the topic?

- 夏は日本へ行くつもりです。

- I plan to go to Japan in the summer.

That's right, it's 夏 (summer) — because that's what comes directly before は. So 夏 is our topic here. In this case, the concept of summer is something that everyone knows about. So, like これ in the previous example, 夏 is the established information, whereas what comes next is the important bit. Whoever said this sentence assumed that the people listening didn't previously know that they were planning to go to Japan.

What about if we were to flip this around, and assume that we know the person is going to Japan, but we don't know when? Then "summer" would be the new information, and "going to Japan" would be the topic:

- [日本へ行くの]はいつですか。

- When is it [that you're going to Japan]?

In this example the whole phrase 日本へ行く(go to Japan) has been turned into a noun thanks to the particle の, and is being used as the topic.

We mentioned earlier that は implies a contrast with other topics. Just like "as for" in English, though, this contrast is on a sliding scale, depending on intonation, and other factors. In the examples we've seen so far, there is not necessarily a strong nuance of contrast.

So when is this nuance definitely present, regardless of intonation? One factor is how unusual it feels to use は in a particular sentence. For example, in the following sentence, コーヒー (coffee) is the object — it's on the receiving end of the action 飲む (drink). So, in the example below, particle を goes after コーヒー to pick it out as the object:

- コーヒーを飲みますか。

- Do you drink coffee?

However, if you were to make コーヒー the topic, that's a little unexpected:

- コーヒーは飲みますか。

- Do you drink coffee?

(Literally: As for coffee, do you drink it?)

Therefore, there's more of a feeling here that we're shining our spotlight on the coffee, but that there are other possible drinks lurking in the shadows. So maybe you've been talking about tea, and now you're moving the conversation on to coffee. Or maybe you want to offer your friend coffee, but also want to imply that there are other options available!

We'll go into this in a little more depth further down this page.

は for Contrasting Two Topics

You can also have two topics in a sentence, in which case the nuance of contrast is generally pretty strong:

- 東京は物価が高いけど、田舎は物価が安い。

- Tokyo has a high cost of living, but the countryside has a low cost of living.

Here you can imagine two spotlights, one highlighting 東京 (Tokyo) and the other 田舎 (the countryside), as we compare the cost of living of the two.

The second topic can also be implied, but not actually stated explicitly.

- 東京は物価が高いけど・・・

- Tokyo has a high cost of living…

In this case, you'll often be able to guess the second topic from context or prior knowledge.

は with い-Adjectives

は can also be added to the middle of the negative form of い-adjectives to add emphasis. So for example, if we want to say that something isn't difficult in a neutral way, we'd take the negative form of the adjective 難しい (difficult):

- 難しくない。

- It's not difficult.

If, however, we slip the particle は in between the く form of the adjective and the ない ending, we end up with this:

- 難しくはない。

- It's not (exactly) difficult.

Here we add a nuance that while this thing is difficult, that's not the whole story. You can imagine the speaker might continue with something like:

- 難しくはないけど、ただ時間がかかる。

- It's not (exactly) difficult, it's just time-consuming.

This works just as well in more formal language, too:

- 難しくはありませんが、時間がかかります。

- It's not (exactly) difficult, it's just time-consuming.

Whether or not the speaker does continue like this, or simply leaves you to guess from context, all depends on how obvious they think it is!

You can also make the adjective positive by switching out the ない for its positive equivalent ある:

- 難しくはある。

- It is difficult.

In this case, there is that same nuance that we don't have the whole story. Perhaps the implication is that it's difficult, but fun or rewarding. This could be left unsaid, or explicitly stated:

- 難しくはあるけど、おもしろい。

- It is difficult, but it's also fun.

は with Nouns and な-Adjectives

は can be also added to the middle of the negative form of nouns and な-adjective, to very similar effect. Here's an example with the な-adjective 有名 (famous):

- 有名ではない。

- They're not (exactly) famous.

Here, you can imagine the speaker might continue with something like:

- 有名ではないが、人気はある。

- They're not (exactly) famous, but they are popular.

And here's an example with a noun, and in a more polite form:

- 先生ではありませんが、説明が上手な人です。

- They're not (actually) a teacher, but they are really good at explaining things.

は and Question Words

Apart from very specific circumstances, は cannot be used immediately after question words like 誰 (who), 何 (what), どこ (where), and so on. This is because — as we've already seen — the topic is always something that is in the listener's consciousness. The very nature of question words is that they are asking about unknown information. If we know, we wouldn't ask the question, right?

So, depending on their role in the sentence, question words may be followed by が, を, etc, but (almost) never は.

- 誰がいましたか。

- Who was there?

It's common to answer a question with は, though:

- 誰が山田さんですか。

- Who is Yamada-san?

- 山田さんはあの人です。

- That's Yamada-san.

(Literally: Yamada-san is that person.)

Here, we've flipped around the answer to make Yamada-san our topic. Since Yamada-san is familiar from the context, it's okay to use them as the topic!

は in Combination with Other Particles

は can be combined with some other particles to make compound particles. However, it cannot be combined with が, を or も:

- 犬が吠えた。

- A dog barked.

- 犬は吠えた。

- The dog barked.

- 犬を見た。

- I saw a/the dog.

- 犬は見た。

- I saw a/the dog.

- 犬もいた。

- A/The dog was there too.

- 犬はいた。

- A/The dog was there.

は can either "replace" に or become には:

- 日本に行ったことがある。

- I've been to Japan.

This sentence sounds like a neutral statement, with no implication that you're making or implying a comparison. You're simply stating the fact that you've been to Japan.

- 日本には行ったことがある。

- I've been to Japan.

By adding は to に, you can add the feeling of comparison that は brings. So you've been to Japan, but maybe you haven't been to Korea, for example.

- 日本は行ったことがある。

- I've been to Japan.

You can also simply replace に with は, to similar effect. Whether you use には or は very often comes down to personal preference, with は alone sounding more casual.

For all other particles, は is simply combined to make compound particles, such as では and とは. In this case, は always goes last, and adds the usual nuance of shining a spotlight on the topic.

- 台所で犬が吠えています。

- The dog is barking in the kitchen.

- 台所では犬が吠えています。

- The dog is barking in the kitchen.

While the first example is neutral, the は in the second sentence adds a slight nuance of contrast, as though we're shining our spotlight on the kitchen and picking it out as the stage of the action.

- 弟と映画館に行きました。

- I went to the movies with my younger brother.

- 弟とは映画館に行きました。

- I went to the movies with my younger brother.

The は in the second sentence above generally adds quite a bit of contrast here. This implication is that you went with your younger brother, but we don't know who else you did or didn't go with. The spotlight is on your brother.

は for Contrast

As we mentioned before, there's always a pinch of contrast with は, because we’re always saying “I don’t know about that other stuff outside this spotlight, but as for my topic…”. But as we've already seen, the strength of the contrast depends on certain factors, such as the nature of the topic, and (in speaking) how much the topic and は are stressed. Let's look at this in a little more detail.

You remember how if は follows something that we wouldn’t expect to be the topic, the contrast is greater? Let's look at a few more examples of what we mean by this.

- 日本語が好きです。

- I like Japanese.

It's pretty standard for が to be used after 日本語 (Japanese) here because 日本語 can be considered the subject of the adjective 好き (likeable). So what if we make 日本語 our topic instead?

- 日本語は好きです。

- I like Japanese (but maybe I don't like other languages/subjects).

Whereas the particle が excludes other subjects and focuses on Japanese exclusively, は gives us the impression that we've contrasting Japanese with other possible topics — maybe other languages, or maybe other subjects in general. So you might be implying that you like Japanese but you don't like other languages, or that you like Japanese but not math.

As we saw above, this nuance of contrast is even more marked if we make an object the topic. So if we say the following, it's neutral:

- お肉を食べない。

- I don't eat meat.

But if we say the following, we're implying something else that we do eat, and contrasting it with meat:

- お肉は食べない。

- I don't eat meat, (but…)

Maybe you don't eat meat, but you do eat fish:

- お肉は食べないけど魚は食べるよ。

- I don't eat meat, but I do eat fish.

Or maybe you don't eat meat, but you do drink beer. Who knows? 🍻

- お肉は食べないけどビールは飲むよ。

- I don't eat meat, but I do drink beer.

Another indicator of how much contrast is involved is stress and intonation. This is pretty similar to English in most situations.

- これはおいしいよ。

- This is delicious.

- これはおいしいよ。

- This is delicious.

The feeling of contrast can also be increased with a pause after the は when speaking, which is generally shown as a comma in writing:

- 日本語は、好き。

- I like Japanese (but…)

- お肉は、食べない。

- I don't eat meat (but…)

Beyond The Basics

は for Hesitating When Speaking

は is often used to buy time when speaking, to give us a chance to think about what we want to say. To do this, it is often combined with the particle ね.

- お寿司は好きですか。

- Do you like sushi?

- お寿司はね…

- Hmm, sushi…

ね isn't obligatory though. You can also simply pause after introducing your topic, to give you time to think:

- お寿司は…

- Hmm, sushi…

When は is Replaced with a Comma

は can be replaced with a comma in writing. The comma has a similar effect to は, but any notion of comparison (or other nuance) is softened. This is very common with time phrases such as 来週 (next week), 先月 (last month), or 今年 (this year):

- 今年は日本に行くんです。

- This year I'm going to Japan.

Here, the implication may be that I haven't managed it in previous years, but, as for this year, I'm going to Japan. If we remove は, the implication of contrast is reduced, and so the sentence leans towards a more neutral interpretation:

- 今年、日本に行くんです。

- This year I'm going to Japan.

Although this is common with time phrases, it's also possible with topics that aren't time phrases:

- 日本語、面白い。

- Japanese is interesting.

- 少し、食べました。

- I ate a little.

In speaking, you can simply pause where the comma is, and this generally creates the same effect!

は for Changing Scenes

は can be used both in conversation and in writing to create a change of scene. By repeating the topic when it's already obvious to the audience, the speaker shines the spotlight back onto that topic and shows that for some reason there is a break in the storyline or a shift in the dialogue.

In the following example, the speaker is describing how her elder brother helped her with her homework yesterday:

- 昨日はお兄ちゃんが勉強を教えてくれた。まず、英語の勉強を教えてくれて、それから国語の勉強だった。でも、算数の宿題をしている途中に、お兄ちゃんはゲームを始めた。

- Yesterday, my big brother helped me study. To start with, he helped me with English, and then with Japanese. But he started playing a game while we were in the middle of doing my math homework.

The first mention of お兄ちゃん (big brother) is followed by が, because he's being introduced into the dialogue for the first time. But then お兄ちゃん is mentioned again, followed by は, when he switches to a different action. This is unnecessary, because it's still obvious that we're talking about the big brother, but it serves to highlight the transition from teaching, to playing a game. It would be perfectly natural not to mention the topic here at all, so the fact that お兄ちゃん is explicitly mentioned again creates this feeling that we are changing scenes in the story. This change of scene effect can be found in both speaking and writing. By repeating the topic when it's already obvious to the audience, the speaker shines the spotlight back onto that topic and shows that for some reason there is a break in the storyline or a shift in the dialogue.

は in Relative Clauses

は is used less in relative clauses than が, but it is still possible under certain circumstances, and to add certain nuances. Look at this example from the children's story どうぞのいす:

- はちみつの びんを かごに いれて いきました。[そんな ことは しらない] ろばさんは くう くう おひるね。

- The bear put a jar of honey into basket and left. Unaware of all this, the donkey kept on sleeping.

It would be more neutral to use を in the relative clause そんな ことは しらない, so why has the author gone for は? By shining the spotlight on そんなこと the author is emphasizing that the donkey is sleeping soundly, completely unaware of what's going on.

Since it's also possible to use の in relative clauses, there are three possible ways to render a sentence like "I was accepted by the school that Jenny failed to get into."

- ジェニーの落ちた学校に私は受かった。

ジェニーが落ちた学校に私は受かった。

ジェニーは落ちた学校に私は受かった。 - I was accepted by the school that Jenny failed to get into.

However, it's worth noting that は can only be used in this way if there is some kind of contrast implied, like in the sentences above. It the relative clause is simply describing the noun, with no nuance of contrast, only の and が can be used:

- ジェニーの落ちた学校に私も落ちた。

ジェニーが落ちた学校に私も落ちた。

❌ ジェニーは落ちた学校に私も落ちた。 - I also failed to get into the school that Jenny failed to get into.