Table of Contents

The Basics

Particle で appears in a lot of different contexts, and is an important particle to wrap your mind around. Its meaning shifts depending on how it's used, but, at its core, particle で helps specify where or how an activity or an event takes place. In this page, we'll walk you through the ins and outs of particle で, always referring back to the underlying concept it represents: specification.

Conceptualizing Particle で

Let's take a closer look at this underlying "specification" concept that particle で represents. We'll use a couple of metaphors to help make sense of this! To start, imagine that particle で is a computer's selection tool. You can use this tool to specify an area on your screen, right?

Well, particle で does the same thing. It often comes after a noun, and specifies that noun as the area where an event occurs. With non-location nouns, it can add other specifications, such as describing how an event happens, expressing the limit of a quantity, and more.

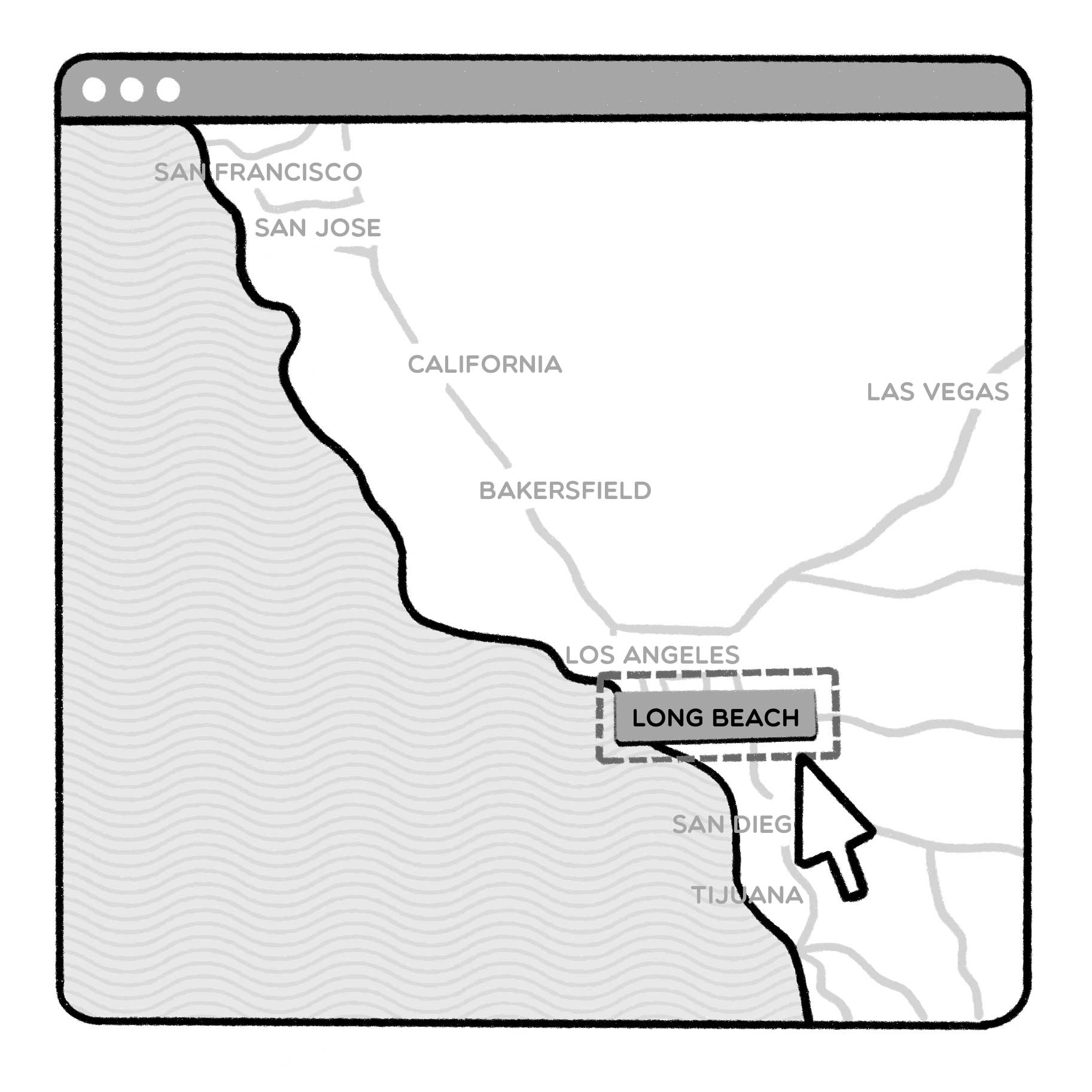

For example, if you add で after ロングビーチ, as in ロングビーチで, it's like you've used a specification tool to demarcate Long Beach as the place where an event or activity occurs.

Learners often struggle to choose between particle で and the other location marker, particle に. In general, the choice comes down to what kind of verb is in the sentence. Long lasting states, like 住む (to live) come with particle に, which acts like a pushpin on a map. Particle で is more common with actions and activities, like バレーボールをする (to play volleyball). So to say, "I play volleyball in Long Beach," you would use で and say:

- ⭕ ロングビーチでバレーボールをする.

❌ ロングビーチにバレーボールをする. - I play volleyball in Long Beach.

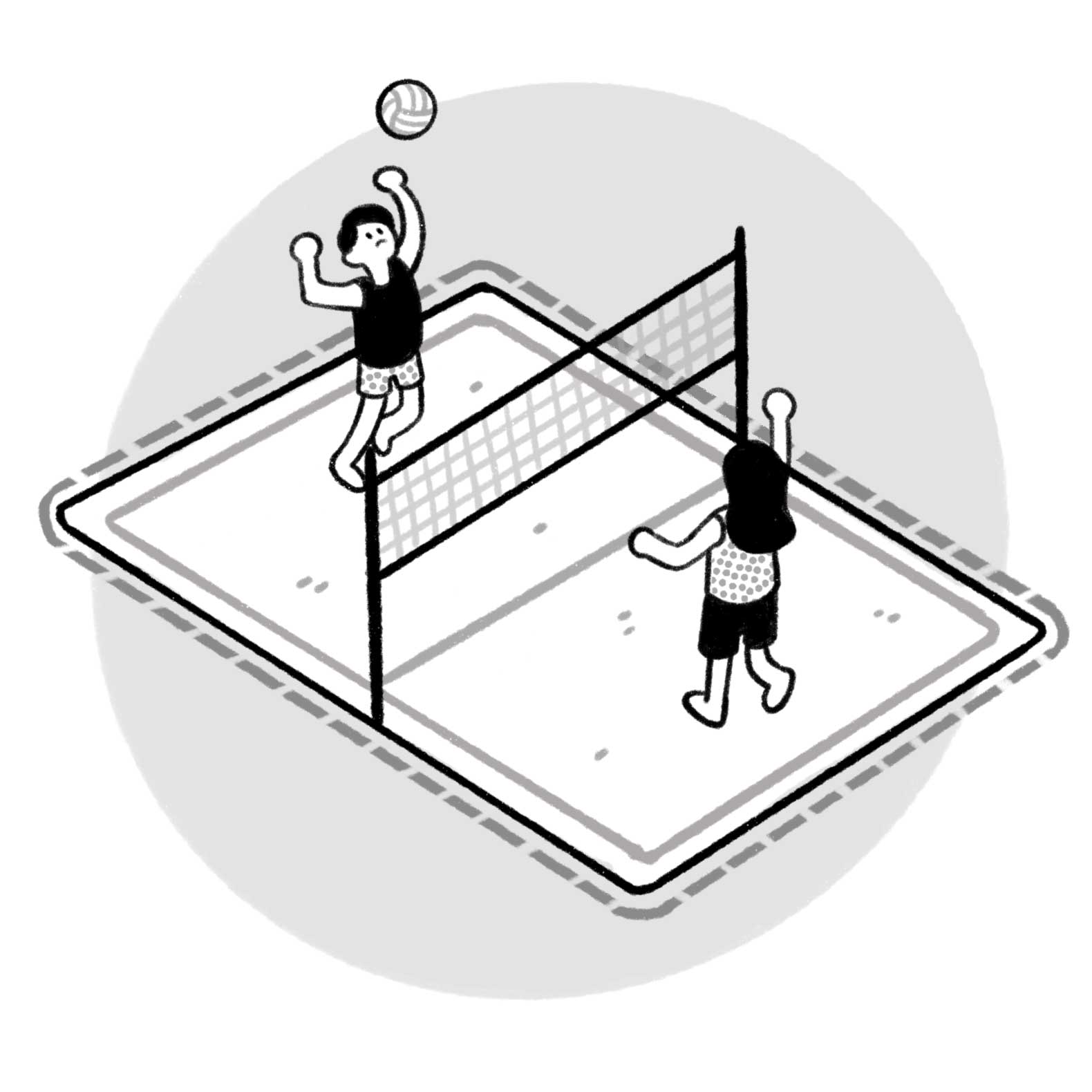

To really drive this difference home, let's turn to one more metaphor. Imagine particle で is like the lines that de(で)marcate the edges of a volleyball court. These lines tell you where the playing area is, and that's what particle で does too.

The lines around the court and the computer's selection tool do the same thing — they specify the area in which the activity will occur. As we move through the different uses of で, which expand beyond just specifying locations, we'll return to these metaphors to help you gain a holistic understanding of the particle.

で for Specifying Places

As we've already discussed, one of the most fundamental uses of particle で is to specify the area in which an action or event occurs. This area is often a physical place:

- ワニがカ二にプールでキスをした。

- An alligator kissed a crab in the pool.

In this example, particle で specifies プール (the pool) as the location of this interspecies kiss. You can imagine that it draws a line around the border of the pool, like a computer selection tool.

The places that で specifies does not necessarily have to be a physical space. You'll often see it with abstract places as well, such as in the following example:

- 私は 貧しい 家庭で 育ちました。

- I grew up in a poor household.

Here, で specifies 貧しい 家庭 (a poor household) as the area that the growing up occurred within. It's not a physical space, since they may have remained poor no matter where they moved to. It sets up the environment they grew up in as the area, or background context.

Particle で can be used to specify other abstract places too, such as electronic platforms or media. For example, if you keep sending funny cat memes to your mom, she might ask you, "Where do you find these😂?" to which you might respond:

- インスタで!

- On Instagram!

See how you're treating it as if it's a virtual location? If the virtual location is the TV, it's' テレビで. If it's a podcast, it's ポッドキャストで. "In a magazine" is 雑誌で and "in a book" is 本で.

This use of で is hard to separate from the next use we'll talk about, which is to specify the means by which an action is carried out. Whether Instagram is the place where you found cat memes, or if it's the means through which you found them is unclear (and up to personal interpretation). The point is that particle で does both of these things. Let's take a closer look in the next section!

で for Means of an Action

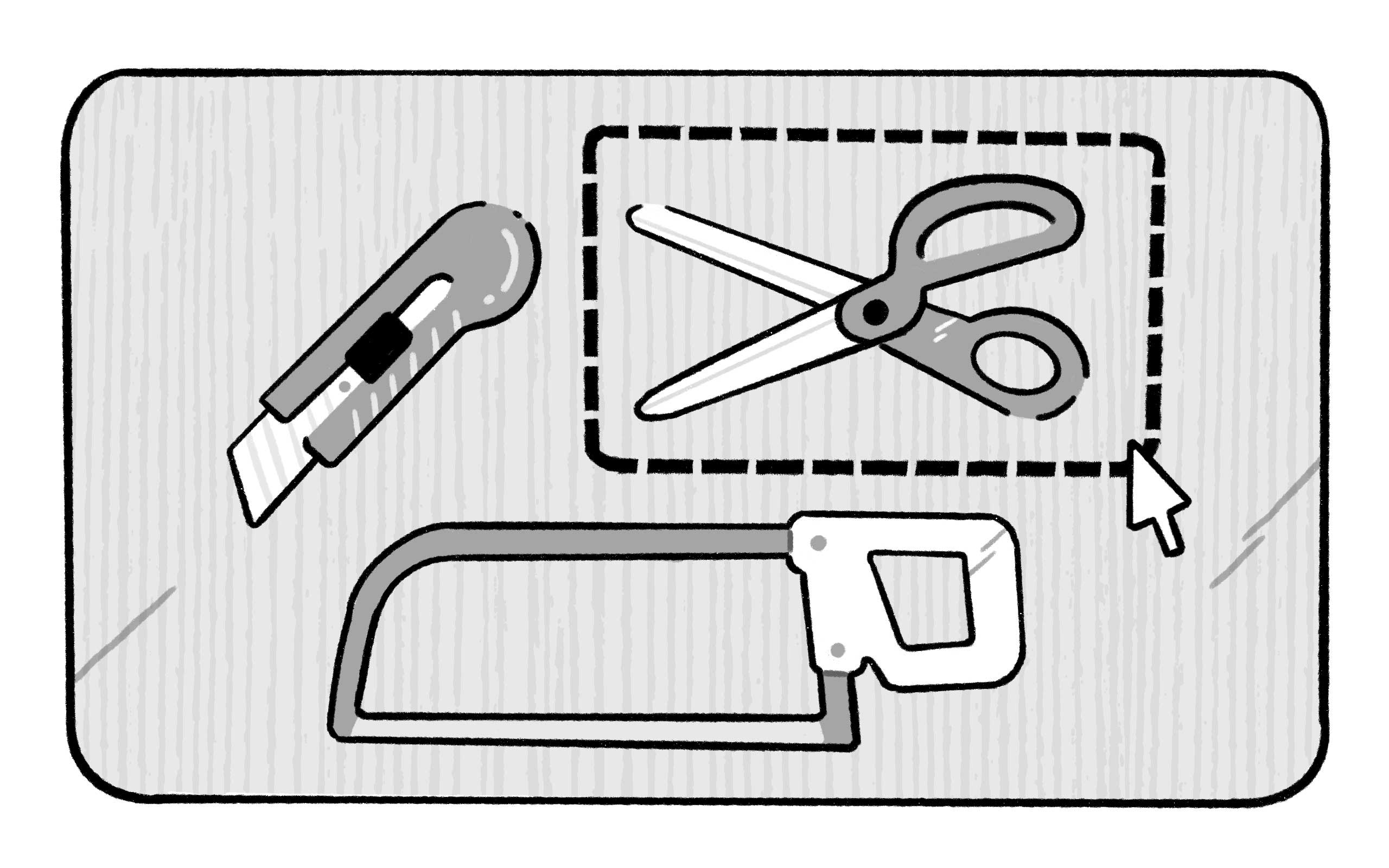

で is used to specify the means by which something is done. Returning to our selection tool metaphor, it's as though で specifies which tool is used by drawing a line around it.

- ハサミで紙を切ります。

- I cut paper with scissors.

In this case, particle で specifies that ハサミ (scissors) are the tool used to cut the paper. We can use particle で to mark a range of different means for doing an activity. For example, if you're planning to go somewhere on foot, you can say:

- 徒歩で行きます。

- I'll go there on foot.

In this example, 徒歩で means "on foot" and the particle で shows that this is the means you selected to carry out the activity of travelling. If you are going somewhere by taxi, it's タクシーで, by bus is バスで, and by train is 電車で. Getting the hang of how it works? It's a pretty easy ride, huh?

The "means" does not have to be a physical thing. で can also mark an abstract means, such as a specific language.

- 日本語で話しましょう。

- Let's speak in Japanese.

In the above example, で specifies the language you want to use for a conversation. You are suggesting that the conversation should take place by means of the Japanese language.

Another nonphysical means that can be selected by で is one's judgment. For example, you can say:

- 人を見かけで 判断するな。

- Don't judge people by their appearance.

To put it simply, this sentence is suggesting not to judge people only by means of their looks. Don't be so shallow!

で for Components

Another use of で is to specify the components of a larger whole. These could be the materials, the ingredients, or the identifiable parts of something. So for example, if you're reading a novel made up of five chapters, you can say:

- この小説は五つの章で 構成されている。

- This novel is made up of five chapters.

Thinking back to the previous section about specifying means, you can see that this use of で is related. The novel is put together by means of five chapters. See what I mean? Let's check out another example.

- このテーブルは木でできている。

- This table is made of wood.

In this example, で specifies wood as the material for the table, telling us what the table is made of.

Or, if you are explaining the ingredients of the cookies you made, you can say:

- このクッキーは、 小麦粉と 砂糖だけで作りました。

- I made these cookies from only flour and sugar.

Here, で specifies flour and sugar as the ingredients for the cookies, indicating that they are what the cookies are made of. In each of the above examples, で specifies the components of a larger whole.

Beyond the Basics

We've now covered the most fundamental uses of particle で. As we mentioned at the beginning of the page, though, で has a lot of uses. In the following sections, we'll introduce you to a few more. As we go, we'll do our best to connect them to our underlying concept of specification. Let's get to it!

で for Categories

Particle で can be used to specify a category. In this use, it's like we're using that selection tool to narrow down the message of the sentence to a specific topic or category. For example, if your friend asked you what your favorite sport is, you might reply:

- スポーツで好きなのはサッカーだよ。

- Among all sports, my favorite is soccer.

In this use, で specifies the category being discussed, スポーツ (sports). Due to the fact that there are many different activities that fall into this category of "sports," it's common to use the phrase 〜の中で with this use. So in our example, we could also say スポーツの中で to mean "among all sports."

Let's take a look at another example. If you want to say Mt. Fuji is the tallest mountain in Japan, you can say:

- 富士山は日本の山で一番高い山だ。

- Mt.Fuji is the tallest mountain among all the mountains in Japan.

In this case, で marks 日本の山 (the mountains of Japan) as the category being discussed. As you can see, we can swap out the 中 from 〜の中で with more specific nouns, such as 山.

で for Quantities and Measurements

Another use of で is to specify quantities and measurements. For example, let's say you're at a farmer's market and see a pile of beautiful tomatoes. You ask how much they are, and the farmer replies:

- トマトは十個で百円です。

- The tomatoes are ten for 100 yen.

In this case, で specifies a quantity of tomatoes as a unit, and a single price is assigned to that unit. Imagine the farmer is using で like a selection tool to draw a line around ten tomatoes and then add a price tag.

This use of で can be applied to measurements too. So, "ten grams for 100 yen" would be 十グラムで百円, and "ten centimeters for 100 yen" would be 十センチで百円. Note that this で is often omitted, and people just say 十個百円, 十グラム百円, or 十センチ百円.

When it comes to measuring speed or velocity though, で cannot be omitted. To express speed in a kilometers per hour format, the Japanese is 時速〜キロで. If you want, you can swap this out for miles too, and say 時速〜マイルで. In either case, the で is a required element. Let's check out this phrase is an example sentence:

- トラックは時速百キロで走っていた。

- The truck was driving at 100km an hour.

So why is the で required here? 時速百キロで describes the way the truck was driving, making the whole phrase function like an adverb. This use of で is one of the areas where it has some crossover with the て form, and in fact particle で is sometimes described as the て form version of だ. The same applies to other speed-related phrases like すごい速さで and すごいスピードで, both meaning "at a very high speed."

で for Groups of People

で can specify groups of people as well. It draws lines around the number of people who participate in an activity or event. For example, if you want to say you live in the house with your husband (so there are two people in your household), you can say:

- 二人で住んでいます。

- Two of us live here.

The group does not have to be a numeric expression like 二人 (two people). If you want to express to your boss that all members of your team worked together on something, you may say:

- 全員で考えました。

- We thought about this all together.

In this example, で draws the focus onto the people who engaged in the brainstorming, which was every team member (全員). You could replace particle で with particle が here, as in 全員が考えました, but the nuance is a bit different. With で, the emphasis is on the means by which the action was done, in this case, by everyone's efforts. Particle が on the other hand simply indicates the subject of the sentence.

This use of で to emphasize people as the means of doing an activity can be used to emphasize who will do something, and who will not do something. For example, let's say you are a private detective. You're investigating a crime, and you run into a police officer. They give you a look of disapproval and tell you to stop sniffing around the crime scene because they'll do the job. To express this, the officer may say:

- 警察で 捜査します。

- We, the police, will do the investigation.

Again, we could use particle が instead of で here without a major change in meaning. By using で, however, you are drawing the distinction between the police and those who are not in the police, and emphasizing that the investigation will be done by the police only. It may imply that they don't want outsiders to be involved.

で for Time Boundaries

で can also be used to specify a time limit or boundary. For example, if you say 五分話します, it means you'll talk about something for five minutes. If you add で after 五分, however, the meaning changes to mean you'll finish the talk within five minutes.

- 五分で話します。

- I'll talk about it within five minutes.

Why does particle で create this nuance? Go back to our metaphor, and imagine that we're drawing lines around five minutes. When we get to the end of the five minutes, we're crossing a boundary out of our specified time, so the implication is that the talk will end at that point. We'll talk about it for no longer than five minutes.

Let's look at another example of this. If you're telling your coworker what time you'll finish work, you can say:

- 今日は三時で仕事を終わります。

- I'll finish work at 3 o'clock today.

In this example, the time marked by で draws a boundary between your work time and your after-work activities. This implies you will perform one activity up until the boundary (until 3 o'clock), and change to another activity after the boundary. In this case, that other activity is probably leaving the office. To say you'll leave at 3 o'clock, you can also use で.

- 今日は三時で帰ります。

- I'll leave at 3 o'clock today.

In this case, で works the same as in the previous sentence, but the activity in focus here is what you'll do after the boundary — 帰る (leave/go home). で still implies that there was an ongoing activity beforehand, and you will go home after the end of that activity.