I recently visited a replica of a traditional Japanese house in the town museum of Takanezawa, Tochigi prefecture. The doors slide open to reveal a doma 土間, or entrance room with a hard dirt floor, from where you can step up to the home's proper floors and rooms. The thin interior walls of the house are made of paper and bamboo, while the shiny wood floors are covered in woven tatami mats made from rice stalks bound with fabric. While every room is simple, there is one in particular that has nothing but a wooden table and silk screens that dot the floor like smooth stones in a serene pond. It's a beautiful room, comfortable and relaxing. I know because I'm lucky enough to have one in my home.

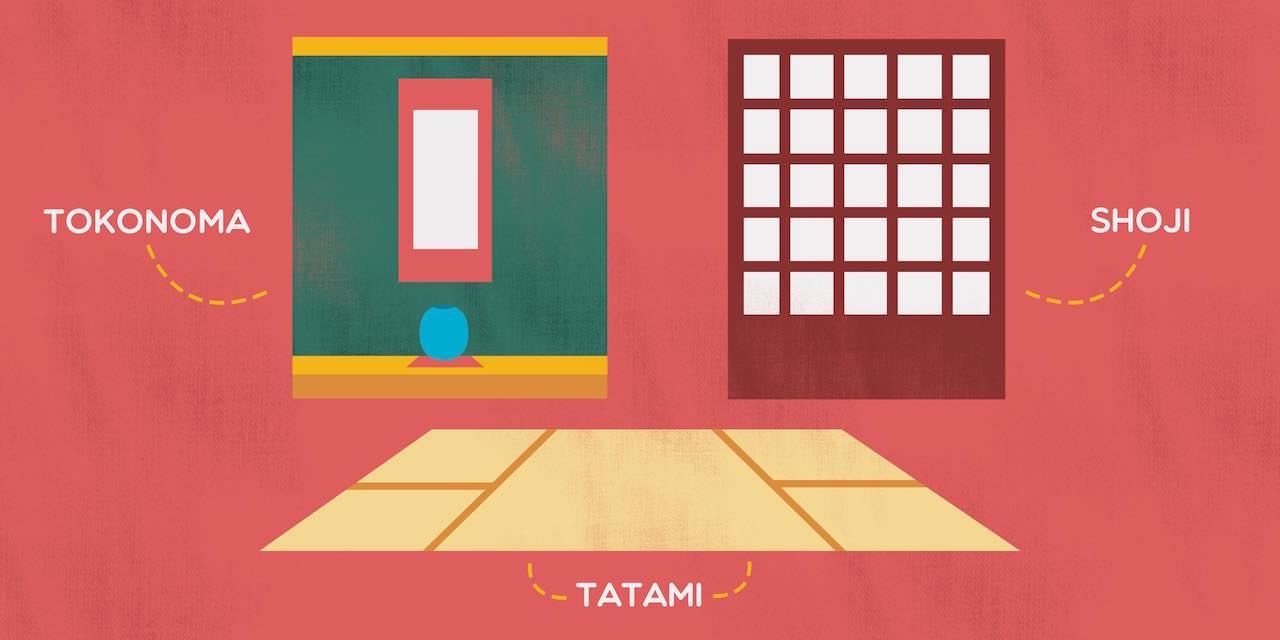

This central feature of traditional Japanese architecture is called the washitsu 和室, or Japanese room. A washitsu is an open room, one that has no dedicated purpose. It has tatami flooring, fusuma sliding doors, and perhaps a tokonoma 床の間, or alcove. Rather than immoveable walls and single-point doors, the washitsu is a place where light and air move easily, where purpose is defined by the needs of the occupants. The washitsu, in other words, is whatever you want it to be.

Other names for washitsu:

- 日本間(にほんま)

- Nihonma (Japanese-style room)

- 座敷(ざしき)

- Zashiki (tatami room)

- 茶室(ちゃしつ)

- Chashitsu (tea room)

What are the elements that make a washitsu?

The washitsu is made up of three traditional elements:

- flooring made from tatami mats

- lightweight sliding doors called shoji

- tokonoma built into the walls

These elements must be built into a room to be a true washitsu. But just as the construction materials in modern Japanese houses have changed from wood and bamboo to steel and ceramics, these traditional elements in washitsu have evolved as well.

Tatami mats

Tatami mats are now mass produced, made from synthetic materials that replicate the feel of traditional tatami while being resistant to fraying, sun bleaching, and rot. This means people can now choose from a wider range of colors than what was available hundreds of years ago, and each color represents a different sense: deep greens represent newness (the color of tatami mats when the rice stalks used to make them still have their color); golden yellow to match the tatami in their prime; gentle tan for a well-lived look, as tatami appears when made from evening stalks.

Tatami mats were and still are made to an exact and uniform size, although that size has varied according to region. However, in every area, mats are made to a strict 2:1 ratio. They've been so standardized that it's not uncommon to measure the size of a house by counting the number of mats. In my house, my 4.5 mat room would be measured as yojouhan 四畳半.

Shoji

Shoji, likewise, have been updated. They are still made from paper and wood, but these materials are now stronger – the paper is more versatile and the woods are more flexible. Modern shoji can also turn corners and fold away when not in use. Some even come with shades to darken the interior of the room and provide more privacy than traditional rice paper doors might.

Tokonoma

The tokonoma serves as a focal point in the washitsu, like a fireplace mantel does in a western living room. A tokonoma, elevated about four or five inches above the floor, is an alcove built into the wall to display flowers and family treasures such as an ancient sword, a gymnastics trophy, or family photos and charms. Hundreds of years ago, however, a tokonoma was a more formal, spiritual space to display scrolls and burn incense.

The Washitsu: Three Rooms in One

In the West, houses have traditionally been built with rooms that each have a dedicated purpose: dining room, living room, playroom, bedrooms, home office. Japanese houses, however, were traditionally built with an opposite approach. Their rooms were designed without built-in furniture or anything else that gives a room a sense of purpose. Instead, furniture was brought in to suit whatever the need of the day or season was. But lately this has changed. With the adoption of bigger, heavier furniture and modern luxuries like TVs and computers, Japanese homes have recently become more like western homes with defined uses of their spaces. Except for the washitsu.

The washitsu retains the flexibility of its heritage and is used today by many Japanese families as a multi-purpose room that can quickly and easily be repurposed to suit, well, just about anything. Generally speaking, though, modern washitsu serve three functions within the house:

- the receiving room

- the family room

- the practical room

And sometimes a washitsu is used for all three of these purposes at the same time.

The Receiving Room

Imagine this: it is late morning on the 1st of January. Snow cloaks the ground outside and at first glance the house is cold and still. But as you walk through the halls and past the standard bedrooms and washrooms, you hear the blare of a TV and happy voices engaged in lively conversation. The shoji slide back to reveal a grandmother and her sisters sitting on warm cushions around a small table with blankets tucked about them.

Teapots, snacks, and the assorted prepared dishes of osechi ryōri お節料理 (traditional Japanese New Year foods) are scattered throughout the area. Decks of cards and other games line the wall behind all the cushions, used by grandmothers waiting for a break in the conversation.

In my house, in my washitsu, this is a yearly occurrence. And it's not just the great-aunts who come around, either. New Year's in Japan is an important time for family and tradition, so the four days around the holiday are packed with all kinds of guests, snacks, and TV specials. And all these people filter through the house into the washitsu.

The center of the room is filled with the kotatsu 炬燵 – a low table with a built-in heater and blankets that are shelved between the heating element and the tabletop itself. In my house, this kotatsu is purpose-built to fit the washitsu. Or, reverse that – my washitsu is built around the kotatsu. There is a deep well beneath my kotatsu where the table can fold up and be stored during the summer, giving us more floor space. In the winter, when the kotatsu is in use, the well provides a welcome respite for those of us – like me – who have a hard time sitting cross-legged for very long, by allowing us to sit on the tatami and dangle our legs, just as we would sit on a chair at a table.

The mizuya douko reinforces the idea that the washitsu is a room for receiving guests.

This low kotatsu is the center point of the room, making it an ideal place to host all those guests. There's an intimacy that comes from gathering together to share warmth and food in a confined, close space like this. As a way to kick off the year, it is hard to beat.

However, there is one traditional element that my house lacks – the mizuya douko 水屋洞庫. Historically, the mizuya douko was a feature found in tea rooms, and it was a built-in cabinet for storing all the paraphernalia needed for serving tea to guests. And although I opted not to have one built when I bought my new house, the mizuya douko reinforces the idea that the washitsu is a room for receiving guests.

It is this combination of features, whether built-in or, like many kotatsu, free-standing, that makes the modern washitsu a perfect receiving room.

The Family Room

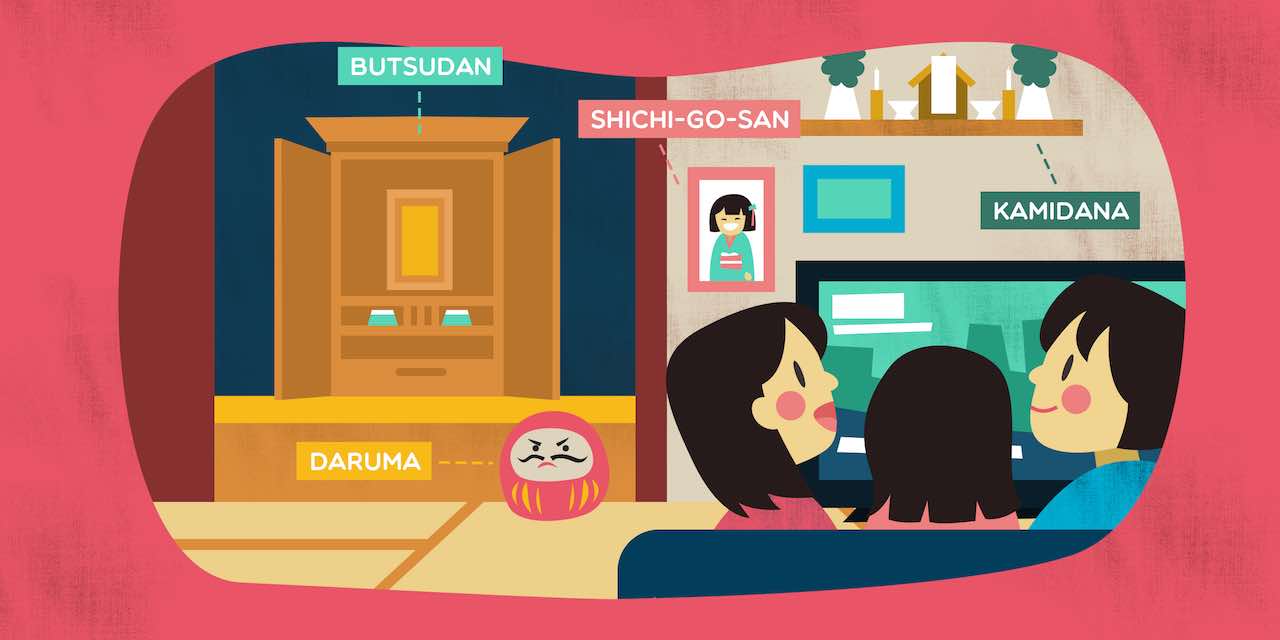

The first time I met my father-in-law, I was shown into the washitsu as a guest. But as time went on and we got to know each other, his washitsu became a family room for me. He took great pride in showing off the familial treasures and gifts they had accumulated over time: the year's daruma 達磨 (good luck doll sold at New Year's); a picture of my wife as a precocious three year old during her shichi-go-san; and souvenirs from trips to Kyoto and Osaka.

A few short years after that, my father-in-law passed away and we added a new feature to the washitsu, the butsudan – a shrine to remember and honor the departed.

Two things that often feature heavily in the washitsu as family room are photos and shrines. I mentioned that my in-laws' family room had pictures of my wife taken during her shichi-go-san ceremony. Between this event, the traditional coming-of-age ceremony, graduations, weddings, and everyone having a camera built into their phone, family photos are more popular than ever.

Two things that often feature heavily in the washitsu as family room are photos and shrines.

Unlike western homes, Japanese houses tend to have very little hung on the walls. Partly this is because of design aesthetics, and partly because of building materials. Traditionally, pictures were hung at an angle using long strings, so that they could be seen more easily by those sitting on the floor. Even then, however, it was not common to see more than one or two pictures on the wall per room.

These days, because the number of ceremonial photos and snapshots documenting our lives has grown so rapidly, special shelving units that will not scuff or damage the tatami are sold at most furniture stores, usually with a plethora of photo frames being sold right next to them. These shelves let the family show themselves off, much like the hallway photo gallery does in western homes.

Beyond the photos, the washitsu seems to be the default place to display religious items, including the year's “lucky goods” (talismans bought at New Year's to bring good luck, good health, or protection). In my father-in-law's washitsu, for example, the kamidana 神棚, a small household shrine for Shinto spirits, rested high on a wall where the resident kami could keep an eye on anyone present below. Other lucky goods were scattered about the room in between photo frames, on top of the TV, stuffed onto the already crowded window ledge, or wherever they would fit. And, although I do not have a kamidana, I do buy my fair share of lucky goods every year. They sit in my washitsu, bringing good luck and health to my family.

So, the family's history and religious traditions are put on display in the washitsu as “family room,” but what do people actually do in there? Aside from the usual family room activities – watching TV, reading a book, playing cards, etc. – people pray. Offerings are placed on both the butsudan and the kamidana. Small bells are rung, incense is lit, and prayers are offered. In this way, among photographs and talismans, Japanese people use their washitsu to remember their ancestors and to pay respect to the spirits around them.

The Practical Room

Space in Japan can be limited. Space to work on your art, or your instrument, or just to sprawl out is hard to find in most Japanese homes. Even if you have the square footage, finding an unobstructed area, one that's free of TVs and sofas and siblings, is difficult. Enter the washitsu.

Earlier, I wrote that my kotatsu can be folded up and stuck into the well below the tatami, leaving the entire room devoid of furniture. With the kotatsu put away, it is a bare room, with no other furniture save the butsudan – tucked away in its tokonoma – and nothing on the walls. Just a green and blonde room where you can do, well, whatever.

Which is the point, really. Remember, traditional Japanese homes were nothing but tatami rooms with furniture that could easily be packed up and moved out of the way, and simple, clean lines that made the few decorations stand out all the more. By keeping the modern washitsu in a similar state, families are able to put their limited space to the best possible use as defined by their needs and interests.

Even if you have the square footage, finding an unobstructed area…is difficult. Enter the washitsu.

Within my circle of friends, family members, and acquaintances, I know of washitsu being put to each of the following practical purposes:

- Child's playroom – okay, that one's mine. Our washitsu is currently my kid's toy room. So much for simplicity.

- Music room – this is a really popular idea. All kinds of guitars, brass, and woodwinds fit into the washitsu as practice space.

- Art studio – like the music room, the washitsu seems to be a popular place for drawing and photography.

- Reading room – specially designed library shelves can be slotted into closets and tokonoma, leaving the tatami and walls free for cushions and pillows

- Dining room – this is very common and, like the shelves, there is an enormous variety of specialty dining tables and chairs that can be placed safely over tatami mats.

The list goes on and on. When I think about the houses in which I lived in the United States and homes where I've been a guest, I'm hard pressed to remember rooms left empty, where it was up to the occupant of the moment to define its purpose. And that is, to me, the greatest appeal and point in favor of the washitsu – by being rigidly defined it is undefined. People are free to use it however they like.

Here to Stay

Washitsu are still popular here in Japan. Recently on Tofugu, I wrote about house hunting in Japan and told you about the model home plazas that abound in Japan. Every model home I visited in three different plazas (about 20, if I recall correctly) had a washitsu in it. Often they had two or three to better show off how that particular company could customize the room for you.

For example, there is one incredible, custom, only-got-it-because-we-asked feature of my washitsu that is neither common nor traditional: it's raised a foot over the other floors in my house, and the entirety of that space is taken up with drawers and storage areas. Which is really convenient given that, as I said, mine is currently a child's play room!

Which is to say, although the washitsu is a culmination and distillation of several hundred years of Japanese architecture and culture, it is still evolving. It is still changing to meet the owner's needs. Whether it is for practice space, hosting space, or just space space, an elegant, simple washitsu will remain a part of Japanese homes for a long while to come.