Mankind has been telling scary stories ever since we decided to start telling stories at all. It only makes sense—a lot of scary crap happens in life. The horror genre was born from folklore and oral tradition that explored death, sadness, and the unexplained, and grew into a contemporary form of entertainment with a host of exemplary graphic novels, literature, games, and film.

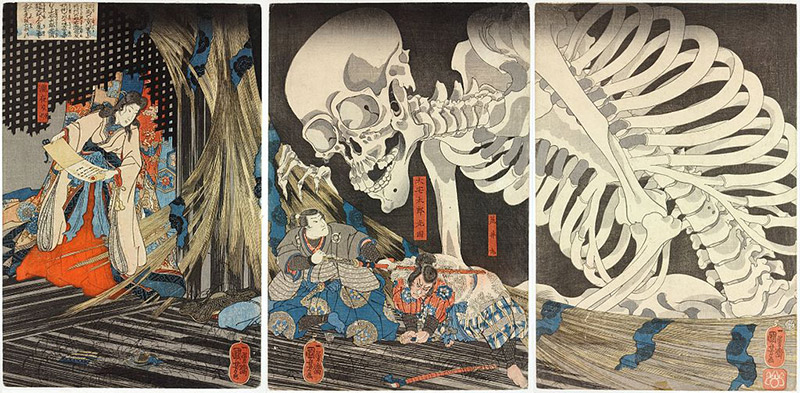

Japan, of course, developed its own tradition of creepy tales entirely independently from the rest of the world. One of the amazing things about Japanese horror is that even with its direct link to traditional folklore and culture, it has proven incredibly popular outside of its country of origin. Japanese horror films, like Ringu and Ju-On: the Grudge, essentially jump-started a love for Asian horror cinema outside of Japan. They prompted Hollywood remakes and they captured the dark imaginations of movie-goers across the globe.

Every last aspect of a classical Japanese horror story’s construction, from structure, to mechanics, to themes and motifs, are integral to the unique sensibilities that have made J-horror so famously eerie. It’s easy to forget how important story structure is to an effective narrative, but the simple details of plot organization and structure determine just about everything that a viewer experiences in a story. In this article, the first of a series about this topic that is so near and dear to my horror-loving heart, I aim to illuminate how plot structure and organization, the blood-soaked backbone of story, contribute to the uniqueness and resonance of Japanese horror.

Visualizing Stories in Japan and the West

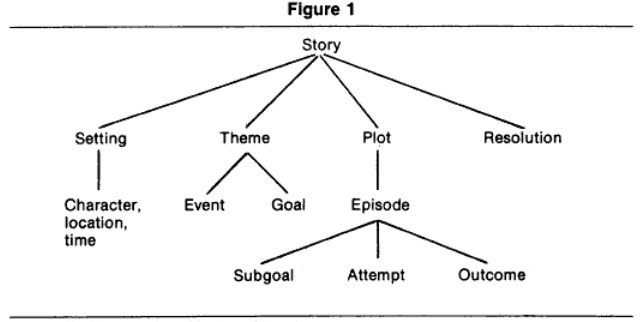

The first thing we need to do is look at the differences in storytelling between the Japanese and Western models. This is the sort of thing that is much easier to do visually by using some established narrative diagramming. One of the tools for visualizing how stories are organized is story grammar which is a (sometimes) simple model that displays the ways that a story’s basic structural components interact to further the plot to a resolution. Think of it as a more nuanced version of the model that is taught in primary school.

To understand how Japanese story grammar is different from the Western model, let’s take a look at the story grammar that a typical Western folk tale might follow, as diagrammed by storytelling scholar Utako Matsuyama:

In a Western story the plot is moved forward by the character’s goals. Bits of story, called episodes, are steered by subgoals that the protagonist needs to accomplish in order to conquer his or her main goal and the successes or failures of that character in meeting those goals determine the outcome. Take “Cinderella” as an example of this Western model of storytelling, she has a clearly defined goal: Go to the ball to hit on the prince. The plot progresses as she encounters opposition to that.

Can a Japanese model of storytelling really be that much more complicated?

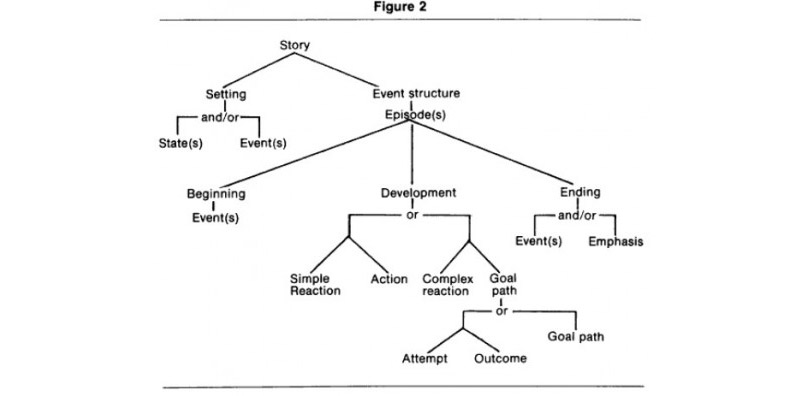

Instead of having goals and subgoals that carry the plot from beginning to end, the classical Japanese story grammar is guided by a series of actions and reactions that lead a character to a thematically significant resolution. Causality, rather than conflict, is the vehicle in this type of storytelling. These stories move based on character actions (or often actions outside of the control of the characters) and the motivations are often irrelevant or not elaborated upon. Matsuyama posits that the lack of a goal structure is due to the traditional Buddhist value of eliminating worldly desires, which is in direct contrast with the very goal-oriented ideas of the West. Japanese protagonists tend to be unmotivated by an initial goal in the interest of making them more classically “good” in a Buddhist sense.

These types of stories tend to follow one of two paths: a simple action-and-reaction structure, or a complex action-and-reaction structure. In a simple-reaction story, the character’s own actions and the universe’s reactions to them drive the story to a conclusion that may or may not have anything to do with character goals. The complex-reaction path is where character goals come into play. Unlike the West, however, it isn’t the protagonist’s goals that drive the story it is the antagonist’s. In these stories, a “bad” character has a goal path that comes into direct conflict with the protagonist, setting events into motion that lead to an ending.

Utako Matsuyama has developed a mock-up of the archetypal Japanese folk tale to illustrate the complex-reaction story structure:

The typical plot would be as follows: the main character is an honest and kind person who happens to help a trapped animal, helpless jizo [statue], or hungry god.

Note, that this wasn’t the character’s goal, it just “happens” to occur. This is the initial action that sets the story in motion.

Following that event, many good things happen to him.

The reaction.

Then, a bad person, usually the good person’s neighbor, sees the good person’s fortune and tries to get the same luck.

Here is the complex reaction, the introduction of another character that has a strong, motivating goal. The end result being that the bad character will get his comeuppance and the good character will continue to blissfully be good and austere.

The ending at the story level is that honesty and kindness are rewarded virtues.

This leads us to the second significant difference between Japanese and Western story grammar: the conclusion. The Japanese story grammar ends with “events and/or emphasis,” whereas the more western model ends with a “resolution.” What that effectively means is that some Japanese narratives don’t need to have a resolution, heavily based on plot events and tying up loose ends. A Japanese story can potentially conclude with plot events or it can end with “emphasis” which is to say that it just ends. The resolution in this case is an emphasis of the virtues or ideas displayed in the story. The nearest Western equivalent that comes to mind is an Aesopian fable that ends with pronounced belief-based morals, or something weird like “The Sopranos” series finale (spoiler alert).

The Grammar of Japanese Horror

Now you know more than you ever wanted about the structure of folk tales (unless you’re into that sort of thing). But how does this contribute to horror stories in Japan? Since horror stories originated directly from folklore, much of Japanese horror has a similar structure with a lack of goal paths for protagonists and the use of an action-reaction model for plotting.

The lack of a goal structure works for horror because, to be an effective horror protagonist, the viewers must sympathize and be able to imagine themselves in the plight of that character. Relatability is the reason that so many J-horror protagonists are ‘everyday high school/college students’ that just want to live normal lives. These characters don’t typically have a strong goal that sets events into motion, rather a series of actions and reactions begins to unfold around them that puts these characters in peril.

The action and reaction model of plot also works wonders for horror, because it creates a sense of helplessness in being subjected to an uncaring reality. For a grisly example of this model we can point to movies in the notorious Guinea Pig series of films. Known for having such realistic effects for blood and gore, an FBI investigation was conducted to determine if they weren’t just snuff films. The first two movies in the series have no plot besides the kidnapping, drugging, torture, and dismemberment of innocent females. These short films are purely driven by actions and reactions and end without any form of proper resolution beyond an “emphasis” on the terrifying things just seen by the audience.

Taken together, these two key ingredients of Japanese story structure give you the essential recipe for typical Japanese horror fiction. An initial action starts the character’s journey. It will either be something they do themselves, like watching a cursed video tape, or moving into an apartment with an upstairs leak. Or else it will be an action by someone (or something) else that directly affects them, like being selected for a dark government program. This initial action will cause them to either become subject to the whims of an outside entity that has a goal of causing them harm, like a vengeful ghost or a deranged killer (consider this the complex-reaction model), or else the reactions beyond their control build up and threaten to consume them, like a curse, disease, or delirium (consider this the simple-reaction model).

So much of Japanese horror fiction follows this basic structure that, if you start looking for it, you might begin to see it everywhere.

Kishōtenketsu and Horror Without Conflict

The components that make the recipe for Japanese horror so complex and eerie are the same components that make Japanese scary stories more likely to be told in ways that defy the traditional three-act structure often seen in the West. In the three-act structure, a problem or conflict appears early on, it reaches a tense climax, and is finally resolved. While this style can work for horror stories (and there are some good examples where it does) there is another model of development that is often employed for great effect with horror stories. That style is called kishōtenketsu 起承転結.

In Japan, kishōtenketsu is a very common way of structuring stories, poems, and even arguments (more on that in another article). To summarize, kishōtenketsu is a four-act structure that contains an introduction (起), development (承), twist (転), and resolution (結). Here’s how it plays out: act one introduces the topic, setting, characters etc. Act two elaborates on this information. Act three, the main event when it comes to horror stories, introduces a major twist that changes the way all the information is perceived. Finally, act four concludes by reconciling what you learned from the first two sections with shocking new information in the third.

Since kishōtenketsu revolves around this twist in the third act, it is not well-suited for describing conflict like the Western three-act model. Instead it conveys discovery and a change of perspective that has far reaching consequences. This works for horror especially well, because, if what you discover in the third act is a little scary, it makes everything else scary by association.

The Worldwide Resonance of Japanese Horror

One of the reasons that Japanese horror has been able to make such a smooth and influential transition to the West and other parts of Asia, is because of the similarity of the Japanese kishōtenketsu style to how horror stories are told elsewhere. There is something very intuitive about having horror stories that operate on a twist ending. I mean, it may sound obvious, but finding out some scary information tends to make people scared, and even more so when you thought everything was okay just before the reveal.

Scary folk tales and urban legends from around the world have used the kishotenketsu model without calling it that. It’s likely that you have heard urban legends that follow the kishōtenketsu model to a T. Take for instance “The Licked Hand” or “The Vanishing Hitchhiker.” If you haven’t heard these already, and they are pretty popular especially around Halloween. Click the links above and give them a read. When you get back I’ll show you how they fit into the kishōtenketsu mold.

The Licked Hand

-

Intro (起): A young girl is home alone with only her pet dog for comfort.

-

Development (承): She hears on the news of an escaped convict and becomes frightened. She is too scared to go to sleep without letting the dog lick her hand from beneath her bed.

-

Twist (転): When she awakes she discovers that her dog is dead and has been the entire night.

-

Conclusion (結): She finds the words “HUMANS CAN LICK TOO” written in blood.

The Vanishing Hitchhiker

-

Intro (起): A young man is driving home in the rain late one night.

-

Development (承): He stops for a young, beautiful woman that is motioning for a ride and offers to take her home.

-

Twist (転): When he arrives at the woman’s house he discovers that the woman has disappeared from his car.

-

Conclusion (結): He knocks on the door of the woman’s house and is informed by an older gentlemen that the woman was his daughter who died four years ago on this very night, still trying to get home.

In stories like these, the twist changes the paradigm and makes the prior events scary, when before they were innocuous. The conclusion answers the questions raised by the twist in a way that situates the story’s plot. Scary folklore like this permeates many cultures outside of Japan and they form the baseline for how these cultures understand horror. The worldwide popularity of Japanese horror can possibly be explained by the fact that the Japanese approach to horror may have transitioned more easily to other cultures than love stories or action stories would if told in the same style.

Only Clawing at the Surface…

Japanese storytellers are markedly innovative and subversive. New ways to tell stories are constantly popping up in books and in cinema, but even contemporary horror stories often show a deep connection to the folkloric tradition of storytelling in Japan. I hope I’ve been able to show that some of the very basic things about story construction can carry a lot of weight.

Please join me next time as I discuss the mechanics of Japanese horror stories, focusing on the use of atmosphere and emotion. For now, I’ve taken up enough of your time—you should be watching scary Japanese movies! Happy Halloween!