Is a rose in full bloom beautiful? How about a decaying flower losing its petals? Are straight teeth or crooked teeth more aesthetically pleasing? Would you rather put a gilded porcelain vase or a warped, weathered piece of pottery in the middle of your living room?

That depends on your sense of aesthetics. Beauty might seem like a self-explanatory concept but it's actually remarkably malleable and culturally variable. Humans like pretty things, but they don't always agree on what qualifies as pretty. Heck, Western academies invented a whole branch of philosophy known as aesthetics just so they could argue with each other about the nature, creation, and appreciation of beauty. And just about every language comes equipped with a vocabulary of aesthetic concepts, a verbal set (or sets) of standards that a culture uses to appraise beauty.

Japanese, of course, is no exception. Biishiki 美意識 refers to one's sense of beauty, and the word is the closest Japanese relative to the English word "aesthetics." However, rather than a philosophy reserved almost solely for the fine arts, biishiki as a concept is much more integrated with all realms of life. There are a slew of aesthetic concepts that fall under this linguistic umbrella, but I'm going to introduce just 7 manifestations of biishiki in this article. Aesthetic vocabulary words in any language are like mini-solar systems, where a single word acts like the gravity gluing together a constellation of related ideas. These little words can mean so much thanks to their decades and even centuries of usage, as layer upon layer of meaning accumulated around a select few phonetic symbols.

Without further ado, let's begin our (roughly chronological) tour of some key Japanese aesthetic concepts.

Miyabi 雅

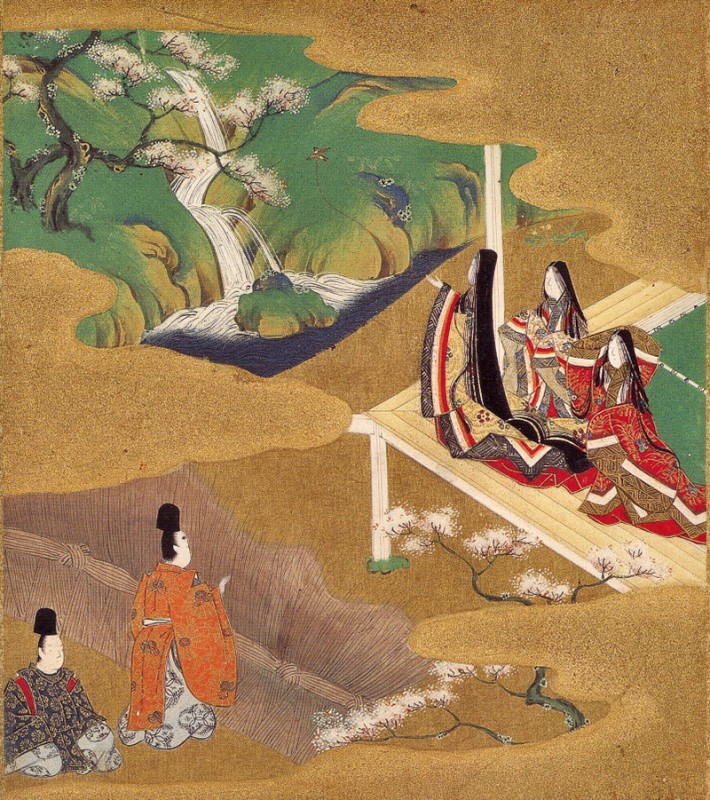

…a spray of plum blossoms, the elusive perfume of a rare wood, the delicate blending of colors in a robe…A man might first be attracted to a woman by catching a glimpse of her sleeve, carelessly but elegantly draped from a carriage window, or by seeing a note in her calligraphy, or by hearing her play a lute one night in the dark. Later, the lovers would exchange letters and poems, often attached to a spray of the flower suitable for the season.

– Sources of Japanese Tradition: From Earliest Times to 1600

In a word, miyabi can be translated as "courtliness." The court in question here refers to the aristocratic court of the Heian period (794-1185) that fostered this aesthetic ideal. Related to the word miyako 都, or "capital," miyabi is all about refinement and elegance. In the Heian period, the capital of Japan was the capital of miyabi.

Cultivating miyabi entails:

- Eliminating all vulgarities, absurdities, crudities, and roughness, and

- Polishing appearances and/or manners to the most graceful possible level.

In addition to objects and experiences, people can also be endowed with miyabi. The miyabi individual is cultured, dignified, and strongly adheres to decorum.

Miyabi's hold over the Japanese cultural imagination had a limiting effect as well as a generative one, since it often prevented the direct expression of "cruder" emotions or unsavory aspects of life. Because really, just how many poems about moon-viewing can you write before you want to stick a calligraphy brush in your eye? Luckily, miyabi is no longer the final word on artistic merit, but it will forever have a place in Japanese culture.

Surprisingly, the miyabi aesthetic ideals of the Heian elites filtered down into the subsequently ruling military class, and from there diffused into the populace at large. As East Asian scholar William de Bary observes about the presence of miyabi in modern Japan, the "love of conventionally admired sights of nature is genuine, not a pose, and it extends to all classes. The annually renewed excitement over cherry blossoms or reddening maples or first snow is an important element of the Japanese year. A letter that failed to open with mention of these sights of nature would strike the recipient as being curiously insensitive." Furthermore, the continued preference for indirect expression in modern Japanese can be traced to miyabi.

Aware/Mono no Aware 哀れ・ 物の 哀れ

The blossoms of the Japanese cherry trees are intrinsically no more beautiful than those of, say, the pear or the apple tree: they are more highly valued because of their transience, since they usually begin to fall within a week of their first appearing. It is precisely the evanescence of their beauty that evokes the wistful feeling of mono no aware in the viewer.

– The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

京にても 京なつかしや 時鳥

Even in Kyoto— hearing the cuckoo's cry— I long for Kyoto

-Haiku By Matsuo Basho

Aware has come a long way in the last thousand years. Many, many moons ago, back at the beginning of the same Heian period that brought you the hit aesthetic concept miyabi, aware functioned as an exclamation of surprise or delight like "oh!" or "ah!" But by the year 1200 aware had gone from a simple "oh!" to a complex emotion. Gradually the word came to be tinted with sadness, an expression of gentle sorrow upon seeing a sight both achingly beautiful and woefully temporary.

In the 18th century aware went through another growth spurt. The groundbreaking scholar Motoori Norinaga expanded and expounded upon the notion of aware as a foundational aspect of Japanese culture in his literary love letter to The Tale of Genji. In his writings, Motoori used the phrase mono no aware (variously translated as "the pathos of things," "empathy toward things," and "the ahhness of things"). He argued that this concept went beyond mere sadness and joy and instead signified "a profound sensitivity to the emotional and effective dimensions of existence in general" ("The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy").

Whether it's called aware or mono no aware, the pathos, empathy, or "ahh-ness" inherent in the concept encompasses a Buddhist awareness of the transient and ephemeral nature of all things, with an accompanying sadness or wistfulness at their passing, as well as a heightened appreciation for their momentary beauty. Deep stuff! In other words, aware is a kind of reverse nostalgia, an aching for the present from the perspective of the future. Aware still inhabits the arts and daily life, finding expression equally in the acclaimed films of Yasujiro Ozu and the annual custom of hanami. And the word has even come full circle as a conversational exclamation, albeit in a more depressing vein. To gasp "aware!" now means something along the lines of "how wretched" or "how pitiful!"

Yūgen 幽玄

…it may be comprehended by the mind, but it cannot be expressed in words…its quality may be suggested by the sight of a thin cloud veiling the moon or by autumn mist swathing the scarlet leaves on a mountainside…

– Shotetsu monogatari in Zoku gunsho ruiju

Of all the aesthetics in this article, yugen might be the trickiest one to pin down. The term made its first appearance in Chinese philosophy texts where it signified "dark" or "mysterious." From the early 13th century through the 15th century, yugen accumulated layers of connotations until it became the marker for a subtly profound, gracefully remote, and deeply mysterious beauty.

One of the two founders of the Noh theater, Zeami, esteemed yugen as the highest possible artistic ideal, and made lasting contributions to its conception. Zeami's writings, almost as obscure and inscrutable as yugen itself, describe yugen as a beauty that leaves empty space for the audience's imagination to fill in, as an aesthetic that prefers allusiveness over explicitness and completeness.

Or as William de Bary describes its effect:

Although the gesture is in itself beautiful, it is the gateway to something beyond as well, as the hand points to depths as profound as the viewer is seeing. It is a symbol not of any one object or conception but of an eternal region, an eternal silence.

Well, then. I'll just let the eternal silence speak for itself.

Jo-ha-kyu 序破急

…I often ask a group of actors to sit in a circle, close their eyes, and clap their hands together, while trying to keep the sound in unison. No leader, no pre-fixed rhythm. Every time, once the group has come together, the clapping will start to imperceptibly speed up until a climax is reached. Then it will slow down again (though not as slow as the original starting point), and once more start to speed up until it reaches a second climax. And so on…This is an organic rhythm which can easily be observed in the body's build-up to sexual orgasm. Almost any rhythmic physical activity will tend to follow this pattern if left to itself.

- The Invisible Actor by Yoshi Oida

These three stages of sprout, flower, and fruit, are, as I said, the jo-ha-kyu of training throughout your life.

– Zeami: Performance Notes by Zeami

Sprout, flower, and fruit? Literally, the compound jo-ha-kyu means "beginning, scattering, rushing." As an aesthetic concept describing temporal and/or spatial movement, jo-ha-kyu originated from the three-part structure (the jo, ha, and kyu) of bugaku court music and dance (practiced by elites since the Heian period). Rather than a "beginning, middle, and end" or a "witch's hat" plot model, jo-ha-kyu is a cyclical structure that gives shape to performances that lack a single climax or clear sectional divisions.

Jo begins slowly, engaging in exploration and building expectation. Ha speeds things up, the unfolding and then scattering of an idea. Kyu dissolves rapidly into the original pace, a culmination of the ha and then a reincarnation as jo. Jo-ha-kyu usually runs through multiple cycles, so that the cumulative effect is of an undulating wave, like the ocean repeatedly crashing on a shoreline—rippling, surging, and cresting, over and over again. To see and hear how this works, check out this video:

For a while, jo-ha-kyu existed only in the bugaku music and dance that accompanied it. But during the Muromachi period (1337-1573) the concept was adapted and incorporated into a wide variety of performance mediums that survive even in modern Japan - from the tea ceremony to kendo to Noh theater. Along with our dark and mysterious friend yugen, Zeami made jo-ha-kyu of central concern to Noh theater. He further argued that the structure expressed the universal pattern of movement of all things, the very rhythm of the universe, from the sexual cycle to the setting of the sun.

Wabi-sabi 侘び 寂び)

Are we to look at cherry blossoms only in full bloom, the moon only when it is cloudless? To long for the moon while looking on the rain, to lower the blinds and be unaware of the passing of the spring—these are even more deeply moving. Branches about to blossom or gardens strewn with faded flowers are worthier of our admiration…

– Essays in idleness (Tsurezuregusa) by Yoshida Kenko, selected by William de Bary to Convey sabi

Miwataseba- Hana mo momiji mo- Nakarikeri- Ura no tomaya no- Aki no yugure

Looking about- Neither flowers- Nor scarlet leaves. A bayside reed hovel- In the autumn dusk.

– Fujiwara no Teika's Poems, selected by Takeno Joo to convey wabi

Though they're basically conjoined twins now, wabi and sabi weren't always attached at the hyphen. Wabi, or wabishii, was once relegated to describe things wretched, dreary, and shabby. Meanwhile, sabi, or sabishii, was the adjective of choice for desolate, old, and lonely things. Around the 14th century, both words got a makeover. Wabi gained the positive or at least neutral connotations of natural, simple, humble, asymmetric. And sabi evolved into graceful, fleeting, aged, weathered. These fuzzy little linguistic caterpillars turned into butterflies, (or maybe moths).

Over time the revamped individual meanings of wabi and sabi overlapped and converged into the unified aesthetic of wabi-sabi. The humble and the aged, the natural and the fleeting—far from being disparaged, or merely accepted, things endowed with these qualities came to be outright celebrated. Not to mention that wabi-sabi had Zen Buddhism on its side. After all, both word and religion encouraged the appreciation of transience and imperfection in nature, humanity, and man-made objects.

As an ironic side-note, the definitionally humble wabi-sabi became so prized that it also became obscenely expensive. During the Muromachi period, large amounts of time and money were spent to acquire and produce flawed, aged objects—objects that now lie in laser-secured glass cases in museums around the world and fetch outrageous sums at auction. Though I suppose that's not a far cry from the phenomenon of "distressed" designer jeans with ludicrously expensively pre-ripped knees…

Shibui 渋い

…as a critical term, the Japanese use the word in innumerable aspects of their everyday lives. "That's a shibui color, isn't it"; "a shibui performance"' "he has a shibui voice"; "her dress is shibui"; and so on. Just as there is shibui material, so there are shibui houses. A sumo wrestler may have a shibui style and so even, may a baseball player…the concept of shibui implies an outlook which is practical, devoid of frills, and unassuming, one which acts as circumstances require, simply and without fuss…neither flashy, nor yet dull…

True beauty lies in its ability to share intimately in one's daily life; in its practical usefulness and its simple efficiency; in its rich human touch; in its ability to create just this kind of healthy relationship…Compared with this, the beauty for its own sake which the word "beauty" usually refers to, even though originally a product of everyday life, has gradually become divorced from life…

– The World of Shibui by Michiaki Kawakita

During the Muromachi period, poor little shibui meant nothing more than "astringent" or "bitter," the antonym of "sweet." It was a word used to describe an unripe persimmon, not a pretty thing. Shibui is still a word to describe an unripe persimmon, but ever since the Edo period (1603-1868) it's also been a signifier of minimalist beauty and of the understated, subdued, and restrained.

The burgeoning commoner class of the Edo era transformed shibui from a literal taste into an aesthetic taste that reflected the virtues of their own songs, fashions, and craftsmanship. On that basis, the shibui forgoes unnecessary frills and rejects the artificially ornamental in favor of overall simplicity and subtle detail.

From the elegantly austere geometry of Edo-period textiles to the sleekly refined design of modern Japanese electronics, shibui has been and continues to be highly influential in Japan. And even if the word itself hasn't become common international currency, shibui does seem to be traveling abroad. The growing global presence and popularity of Japanese retail outlets like Uniqlo and Muji (selling shibui clothing and shibui home goods) suggests that 17th century Japanese commoners would be quite pleased if they somehow time-traveled to the 21st century.

Iki 粋

…Iki developed in a social context in which one found no faces blackened by the sun, no tough palms or stout, strong-jointed fingers, no conversations shouted in broad dialect. The rough behavior that might accompany tilling, logging, fishing, or salt making was entirely out of place. Indeed, any activity taking place in fields, forests, or waters—activities in which efforts were directed at the nonhuman—were incompatible with iki. Iki emerged entirely from the subtle tensions in human relationships…an aesthetic of the metropolis…the realm of possibility, a realm in which relations between people maintain a subtle vibrating tension, appearing and vanishing, at once weak and impassioned, both intimate and distant.

– Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan, 1600-1868 By Matsunosuke Nishiyama

One beautiful April morning, in search of a cup of coffee to start the day, the boy was walking from west to east, while the girl, intending to send a special-delivery letter, was walking from east to west, but along the same narrow street in the Harajuku neighborhood of Tokyo. They passed each other in the very center of the street. The faintest gleam of their lost memories glimmered for the briefest moment in their hearts. Each felt a rumbling in their chest. And they knew:

She is the 100% perfect girl for me.

He is the 100% perfect boy for me.

But the glow of their memories was far too weak, and their thoughts no longer had the clarity of fouteen years earlier. Without a word, they passed each other, disappearing into the crowd. Forever.

A sad story, don't you think?

Yes, that's it, that is what I should have said to her.

– "On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning" By Murakami Haruki

Basically, iki was cool before "cool" was cool. Like shibui, iki emerged from Edo period urban culture, particularly from the burgeoning brothel and theater districts. The essence of iki is the essence of urbanity, an effortlessly stylish and unpretentious chic that is both alluring and aloof.

According to Edo period historian Matsunosuke Nishiyama, the three main ingredients of iki were:

- Hari, a "straightforward, coolly gallant manner,

- Bitai, a "flirtatious allure and light coquettishness,"

- Akanuke, an "unpretentious air…an unconcerned, unassuming character."

Iki can broadly apply to someone's persona (of either gender) as well as to experiences and to man-made phenomena like films, urban landscapes, and fashion.

After the Edo period came to an end, iki faded out of cultural consciousness until the 1930s, when Kuki Shuzo re-popularized the concept with his influential philosophical tract, The Structure of Iki. Since then iki's been alive and well. Heavily urbanized modern Japan serves up iki everywhere from Murakami Haruki's writing (often cited as an embodiment of iki) to the "host clubs" that populate entertainment quarters (and deliberately cultivate an iki atmosphere for their female clientele).

Roses Are Dead, Violets Are Too

For every biishiki term I covered, there's a dozen I had to leave out. So if this sampling's got you hungry for more, there's plenty to choose from. Check out this article for coverage of the kawaii craze (an aesthetic concept that arose in the 1970s) or pick up a copy of Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader by Nancy G. Hume for a general (but thorough!) overview. That said, even the seven concepts I did cover have a whole lot more to offer. I chose them because they're particularly meaty and foundational to Japanese culture, but that also meant that I had to leave quite a bit out. After all, there are entire books worth of material in multiple languages dedicated to just about every one of them. So if one of the above biishiki particularly strikes your fancy, you can be assured I only scratched the surface.

You know when you learn a new word and then suddenly you start seeing it everywhere? Whether you're super into traditional Japanese screen paintings, dream of touring famous sites in Kyoto, want to try your hand at learning kendo or tea ceremony, or get invited to take part in a hanami picnic, you'll start seeing biishiki popping up everywhere. Even if you're just walking around your own backyard in the dead of winter, or using a particularly well-designed object—you'll start seeing wabi-sabi and shibui where you would have seen nothing particular before. At least that's how I felt when I first learned about all these concepts. They're each like a pair of glasses that can uniquely frame and filter the world around you, giving definition and shape to previously blurry surroundings. Suddenly, decaying flowers can be just as beautiful as blooming ones. And now you don't have to worry about watering them regularly.