Samurai get too much credit. Japan's foot soldiers, the ashigaru, started as nothing more than farmers pulled from the fields to swell a daimyo's army. Yet as time passed they became a professional fighting force included in the samurai caste. Stories like to depict Japanese wars filled with samurai sword duels. But the truth is that samurai themselves lamented the rise of "ashigaru warfare" as the humble foot soldier stole their thunder.

The Origins of Ashigaru

Ashigaru were foot soldiers that made up an extremely large but historically silent part of ancient Japan's armies. Understanding them, though, first requires a look into the origins of samurai. The image most of the world has actually comes from the final, dying days of the warrior class. It was only after Japan was unified and its civil wars ended that samurai became master swordsmen. In the earliest days of Japanese warfare, samurai served primarily as mounted archers. The earliest accounts don't even mention swords, but instead judge samurai by how well they could use a bow.

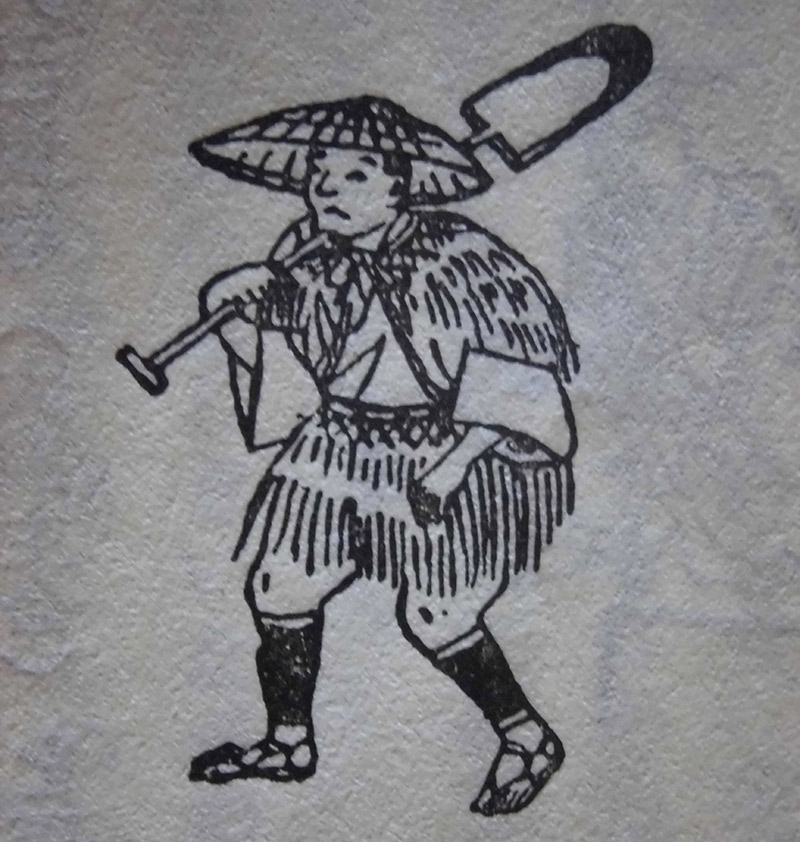

War on foot was primarily carried out by conscripted farmers. They were an untrained bunch, though, and the weapons they used were either farming tools or those looted off dead samurai. Not considered soldiers so much as fodder, they were neither outfitted nor paid. Compensation came in the form of loot, which turned out to be substantial. Being an ashigaru proved far more lucrative than being a simple farmer. This led to large numbers of vagabond fighters tagging along with samurai armies.

The Shady Years

Peasants quickly realized that fighting wars could make them wealthier than working the land, and many simply gave up farming to become full time fighters. Another kind of ashigaru was born, one who prowled the edges of the battlefield joining whichever side seemed more likely to win. They were mercenaries, unreliable and unruly. Their rate of enlistment was as high as their rate of desertion. Many of them didn't even know where they were or which side they were on. As long as it was the winning side and there was money to be made, it didn't matter.

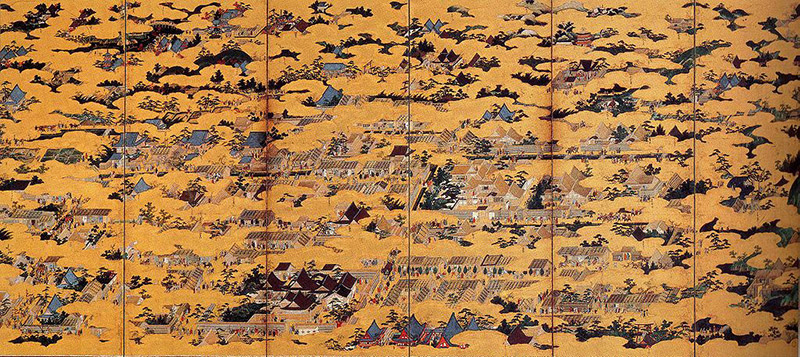

This unscrupulous brawler gave the ashigaru a shady image, which was cemented when they burned down the area that was to become Kyoto during the Onin War. They were branded as a dangerous, almost criminal element. Samurai tolerated them only because they were necessary for war. This is why we never hear about them except in the background of tales about samurai. Japanese writers were more interested in writing about the noble warrior class than peasant mercenaries.

But Japanese warfare was heating up and ashigaru had become proto-soldiers. The samurai were always a well-trained fighting force, but once large numbers of ashigaru mercenaries entered the fray, warfare intensified. The ashigaru were now semi-professional, and somewhat competent in a variety of weapons. One of which, the uchigatana, would help forge samurai into what they later became.

Early accounts had samurai battles being private duels that moved through a series of weapons and ended in hand to hand brawling. While these stories were certainly exaggerated, what we can clearly see was that they didn't have any special preference for swords. Katana actually evolved from an ashigaru weapon called an uchigatana, which was essentially a cheap, disposable katana. Uchigatana could be both drawn and used to strike in the same motion.

Samurai, meanwhile, had been using an earlier type of sword called a tachi, which required two separate motions to draw and strike. As Japanese warfare became more fierce, samurai needed a faster sword. They quickly adopted the ashigaru uchigatana, which later evolved into "the soul of the samurai."

An Upwardly Mobile Class

As daimyo's campaigns became increasingly lengthy, victory didn't favor the bold, but the rich. Wealthier rulers grew even more powerful because they had enough resources to keep men both at war and at home tilling the fields. The transformation of ashigaru from vagabond to professional soldier began when rulers started preferring full-time soldiers to seasonal ones.

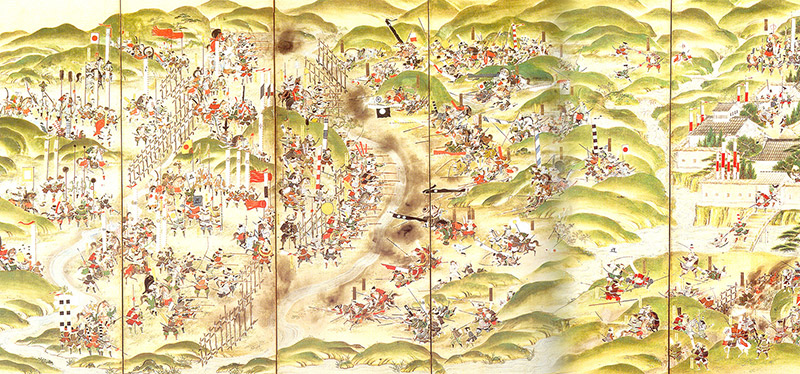

As daimyo relied more and more on ashigaru, they began outfitting them with better weapons. Most notably, they were trained in the use of bows so they could meet an enemy's calvary charge with a volley of fire. But now that bows were in the hands of commoners, the image of samurai as elite archers disappeared. It was much to the dismay of many samurai philosophers, who called the change of tactics "ashigaru warfare."

Another weapon ashigaru had in common with the samurai was the spear. Samurai actually fought with spears long before they even touched their swords. They were actually told not to have a favored weapon, since they would have to rely on many throughout a battle. There is evidence that at times even the upper ranks of samurai fell to a skilled ashigaru spearman, who likely received a promotion to samurai upon presenting his master with their head. Ashigaru spear units were particularly prevalent due to the cheapness and effectiveness of the weapon.

Since ashigaru were using the same weapons as samurai, they started receiving some of the same extensive training. The fighting prowess of some ashigaru became so well regarded that the more elite members even served on daimyos' personal guard. Their skills rapidly closed in on and at times even surpassed the samurai. One famed general boasted that he could make 10 ashigaru fight like 100 samurai. These ashigaru commanders were called "ashigaru taicho." Despite having command over mere commoners, they were listed among the elite of Japan's generals. Ashigaru came not only to be recognized as valuable assets of war, but the first step for commoners wanting to become full-fledged samurai.

Ashigaru and Guns

The samurai hated guns. The rifles Japan had received from abroad offended Japan's warrior class. The idea that anyone, even a lowly peasant, could kill a fully-trained samurai with only the twitch of a finger was an insult. Even the bow was preferred to guns since it took years of training to master. Guns, on the other hand, took only a few days to learn.

But daimyo saw the potential of guns, and were more concerned with securing victories then cultivating their servants' honor. They quickly absorbed firearms into their armies. Given the samurai's hatred of the "crude" weapon, when guns were introduced to Japan they were deemed peasant fare, and largely placed in the hands of the ashigaru.

To say firearms were the deciding factor in ending Japan's seemingly endless civil wars would be an overstatement. But without them it isn't likely Oda Nobunaga would have been able to put down his rivals to succeed in unifying Japan. They played a key role in his battle against rival daimyo Takeda Shingen's feared calvary force. Their battle was a turning point for the ambitious, young Nobunaga's quest for power. He had incorporated firearm-equipped ashigaru into his front lines, who met the mounted charge of Takeda's samurai with a volley of rifle fire. It broke the Takeda charge, allowing Nobunaga's forces to eventually win the battle, but also making rifle-wielding ashigaru a critical part of the fighting.

The Ashigaru Who Became Master of Japan

The most notable ashigaru was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who rose from humble peasantry to become the undisputed master of Japan. Hideyoshi was the adopted son of an ashigaru under Oda Nobunaga, the unifier of Japan. Though it's somewhat disputed, it's said that Hideyoshi was Nobunaga's sandal bearer. Regardless of his exact position, though, he rose to become one of Nobunaga's generals after a series of successes.

After his master's death, Hideyoshi supported his grandson's succession, though he was actually only grabbing power for himself. After a series of conflicts he eventually succeeded in putting down his rivals, and assumed Nobunaga's place as the master of Japan. Although the system wasn't designed to allow peasantry to climb to the very height of political and military power, it happened. Being an ashigaru was the one avenue that the son of a farmer could become the most powerful man in Japan. All it took was talent, a lot of ambition, and a little political scheming.

At this point, though, things changed for the ashigaru. Hideyoshi feared another commoner rising to take his place one day, so he kicked the ladder out from under any potential usurpers by freezing Japan's class system. The result, though, was that any fighting man was now considered a samurai. Under Hideyoshi, ashigaru had officially joined the warrior class. Though there were different ranks that determined benefits like like pay and land ownership, as time elapsed, there was no distinguishing between ashigaru and higher ranks of samurai. The line separating them had grown too thin.

The Rise to Samurai

While samurai get all the glory, the ashigaru were fighting alongside them from the very beginning. Centuries of battle had transformed them from conscripted farmers into fighters of, at times, equal skill. Eventually, it came to the point it is now. When we say the word "samurai," we don't realize that we're also saying "ashigaru."