When you think of Japan, certain traditionally 日本的 (typically Japanese) things spring to mind. There are some things so ingrained in Japanese culture and history that you can't help but picture a Japanese person in association with them. And this includes traditionally Japanese jobs.

However, in modern Japanese society, there are certain foreigners who have found a way to make a name for themselves even in traditional jobs in Japan. Despite the worldview that some areas are reserved for native-born Japanese people, these local celebrities have proven otherwise.

Rakugo

Rakugo is a form of Japanese comedic storytelling dating back to the 9th century. It was originally called karukuchi 軽口, meaning "talkative." But texts describing it have also called it otoshibanashi 落し 噺, meaning "falling discourse." The term rakugo 落語 literally means "fallen words," and was first used during the Meiji Era.

During a rakugo performance, a lone performer sits onstage and tells a story. And it can last several hours. The only props allowed are a paper fan 扇子 and a small cloth 手拭. Rakugo performers, or Rakugoka, cannot leave the seiza position throughout the entire story. And since rakugo is performed solo, the rakugoka must do all the voices of the characters, including dialogue, with only slight changes in tone and pitch to show who's speaking. Thus, rakugo has been described by Professor Noriko Watanabe as "a sitcom with one person playing all the parts."

Rakugo was invented by Buddhist monks as early as the 9th century. Its written tradition can be traced back to the collection of stories Uji Shūi Monogatari. The monks used rakugo as a way to make their sermons seem more interesting and to better relate to their constituents. It eventually spread throughout Japan.

Modern rakugoka must be accepted as apprentices to rakugo masters before they can perform. And there are only two rakugo training centers in Japan. After observing their master and practicing the art, a rakugo apprentice can have their professional debut. They eventually finish their apprenticeship to become a full-fledged rakugoka.

In the history of rakugo, only three foreign rakugoka have been considered true professionals. The first was known as Kairakutei Black. Born Henry James Black in Australia in 1858, he lived in Japan from the time he was three years old. Black started out telling jokes and stories to people outside his father's publishing company. He became the first foreign rakugoka after a master took a liking to him. Black became a rakugoka against his family's wishes. He eventually severed all ties and was adopted by a Japanese family and took Japanese nationality. Black died on September 19th, 1923, and is buried in Yokohama Foreign Cemetery.

Bill Crowley is another foreigner who was able to become a professional rakugoka. He was assisted by Katsura Shijaku II, but never became an official apprentice. As a part of the HOE International performing troupe, Crowley worked alongside several other foreign aspiring rakugoka. Crowley was also a pioneer in the field of English-language rakugo, positing that the universality of the experiences described in rakugo stories bolsters its appeal across languages.

Besides Bill Crowley, the only foreign rakugoka currently performing is Katsura Sunshine. Born Gregory Robic in Toronto on April 6th, 1970, Sunshine originally studied classics at the University of Toronto. He came to Japan to study Noh and Kabuki, and worked as an English teacher at Daigakushorin International Language Academy. In 2008, he became an apprentice to Katsura Sanshi (now called Katsura Bunshi VI). Sunshine received his rakugo name in rakugo tradition, taking his master's last name and a part of his first. He combined the "san" from "Sanshi" with the character for "shine," pronouncing it "sunshine." Sunshine debuted in Singapore in 2009, and completed his three-year apprenticeship in November of 2012. Sunshine is the first ever foreign professional rakugoka in the Osaka-based Kamigata tradition. Kairakutei Black was an Edo-style rakugoka.

Sunshine lives in Ise City, where he regularly performs at his own rakugo theater, Ise Kawasaki Kikitei. He also has performed in Singapore, the United States, Canada, England, Scotland, France, Australia, Sri Lanka, and Hong Kong. Sunshine appears often on Japanese television, and even performs rakugo in English in the West.

Sunshine has remarked that audiences often tell him that they are either amazed by how fluent and native-like his Japanese is, or that his Japanese isn't nearly good enough for rakugo. So he says that reactions to his performances balance out in the middle.

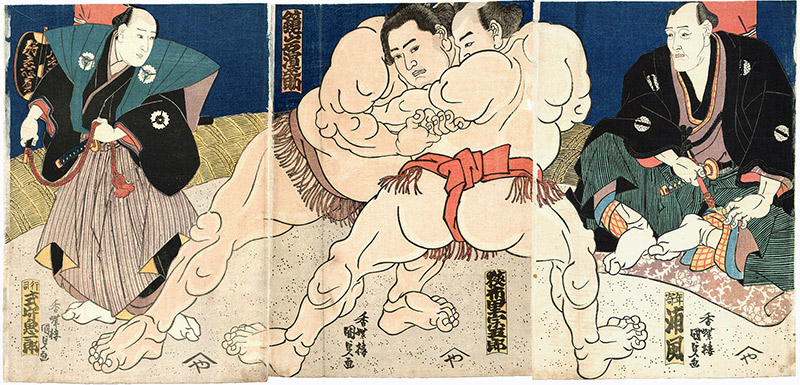

Sumo

We can't talk about traditional Japan and not mention sumo. Sumo is one of the oldest Japanese sports, but its exact origins are not clear. One theory is that sumo is the result of influences from other Asian countries. Mongolian wrestling (Bökh), Chinese wrestling (Shuai jiao 摔跤), and Korean wrestling (Ssireum 씨름), are all similar to sumo, and none has a definitively known creator or creation date. So it is highly possible that one of these other forms of wrestling is the parent sport of sumo.

Another theory is that sumo is based on ancient Shinto rituals. Representatives would wrestle with kami. Defeating the spirit meant a successful harvest was assured. The salt used to purify the ring before a match also has roots in Shintoism. The ring came from the 16th century, when Oda Nobunaga organized a nationwide sumo tournament, requiring an official ring and stands for spectators. Matches were held on the grounds of a shrine or temple until sumo become a professional sport during the Tokugawa period.

The first professional sumo rikishi were actually rōnin, masterless samurai who needed a new form of income. Professional tournaments began in 1684, taking place primarily in Tokyo during the Edo era. But Kansai had its own sumo, with Osaka functioning as Japan's original sumo capital. In 1926, Osaka sumo merged with Tokyo sumo, and the Ryōgoku Kokugikan stadium in Tokyo became the new exclusive venue for sumo matches.

Sumo is still a celebrated sport of Japan, though a series of controversies and scandals concerning hazing, match-fixing, and even murder, have shaken the public's faith in recent years.

Despite traditional roots, many foreigners have had great success in sumo. Akebono Tarō, born Chad Haaheo Rowan in 1969 in Hawaii, became the first non-Japanese-born wrestler ever to become the yokozuna, the highest rank in sumo. Since then, five other foreigners have become yokozuna, chief among them Hakuhō Shō. Hakuhō was originally known as Mönkhbatyn Dayaajargal, born March 11th, 1985 in Ulan Bator, Mongolia. Hakuhō's father was a darkhan (the equivalent of a yokozuna) in Mongolian wrestling, and even won the silver medal in freestyle wrestling at the 1968 Summer Olympics.

Despite this, Hakuhō's father discouraged him from wrestling because he considered his son too small. When he was 15, Hakuhō was invited to come to Japan by Kyokushūzan, another Mongolian sumo. But Hakuhō was only 137 lbs, far too light to be an effective rikishi. Thus, no stable was willing to accept him until Kyokushūzan intervened and convinced the Miyagino stable to take him in. In 2001, Hakuhō made his professional debut in Osaka. Though he lacked real wrestling experience, Hakuhō climbed the ranks and grew bigger and bigger. He eventually reached 6'4" and 346 lbs.

Hakuhō was promoted to ōzeki, the rank just below yokozuna, in March 2006 a few weeks after turning 21. He was the fourth-youngest wrestler to reach ōzeki in modern sumo history. In 2007, Hakuhō became the third ever foreign-born yokozuna after winning two consecutive tournaments, one with a perfect 15-0 record.

Hakuhō is still an active yokozuna. He holds records for the most wins in a calendar year, the most undefeated tournament championships, the second longest winning streak in sumo history, and the second most wins of all time in the top division.

Sumo Association chairman Kitanoumi, a former yokozuna himself, has commented that "Nobody can touch Hakuhō… I'd like to see him go for 40 titles. If he keeps going the way he is, that's a possibility."

Enka

Before AKB-48 and Arashi, there was a different kind of music that defined Japan; enka.

The term "enka" was first used to describe a series of "songs" from the Meiji era. These songs were actually political speeches in protest of the Meiji government. But strict laws against political dissent meant that people could not deliver speeches. So they found a loophole by singing their thoughts instead. Thus, enka was born.

As time went on, enka evolved, incorporating both traditional instruments like shakuhachi and shamisen, as well as more modern instruments like violins, guitars, and other percussion.

During the 1940s, jazz became popular in postwar Japan, which helped start the careers of many enka singers. Kasuga Hachirō is considered the first modern enka singer. His 1954 hit "Otomi-san" sold 500,000 copies in six months, and eventually went on to sell over one million copies. Enka's popularity continued well into the 1990s, even beating out Elvis Presley in Japan. However, with Kasuga's death in 1991, enka began losing out to more modern music like J-pop.

Younger Japanese people were not impressed by enka, and preferred more Western style music. But during the early 2000s, a new form of "hybrid enka" emerged. This new form is a cross between traditional enka and hip-hop, rap, and rock. Enka suddenly saw a resurgence in popularity.

The first non-Japanese enka singer was Sarbjit Singh Chadha, an Indian man. He released an enka album in 1975 that sold over 150,000 copies. In 2002, Yolanda Tasico became the first enka singer from the Philippines who released several singles in Japan.

In recent years, the most popular foreign enka singer has been Jero, an American. Born Jerome Charles White, Jr. in Pittsburg, PA in 1981, his maternal grandfather was an African-American who met his Japanese wife during his time as a serviceman during WWII. They had a daughter, Harumi, and eventually moved back to his hometown of Pittsburgh. Since Jero's parents divorced when he was young, his grandmother helped raise him. This instilled in him a strong sense of Japanese culture and identity. She was the one who introduced him to enka. He began singing at the age of six, and by the time he was ten he could sing hits by great enka artists.

Jero studied Japanese all throughout high school and college. He moved to Japan after graduating with a degree in information technology from the University of Pittsburgh. He worked as an English teacher and computer engineer, but still wanted to become a professional enka singer. He'd promised his grandmother that he would one day perform at the annual Kōhaku Uta Gassen song show. Unfortunately, she died in 2005, just three years before his single "Umiyuki" was released. It entered the Japanese charts at number 4, cementing Jero as an enka professional, as well as the first black enka singer ever. He won the Best New Artist Award in the 50th Japan Record Awards on December 30th, 2008. He finally fulfilled the promise he made to his grandmother when he performed at the 59th Kōhaku Uta Gassen.

Although his lyrics are those of traditional enka, Jero's performances are influenced by hip-hop. He wears jerseys, sneakers, and baseball caps instead of the kimono that enka singers usually wear. His traditional lyrics appeal to the nostalgia of older fans, while his modern image appeals to younger fans. Jero tours both in Japan and in the US, bringing enka across the Pacific.

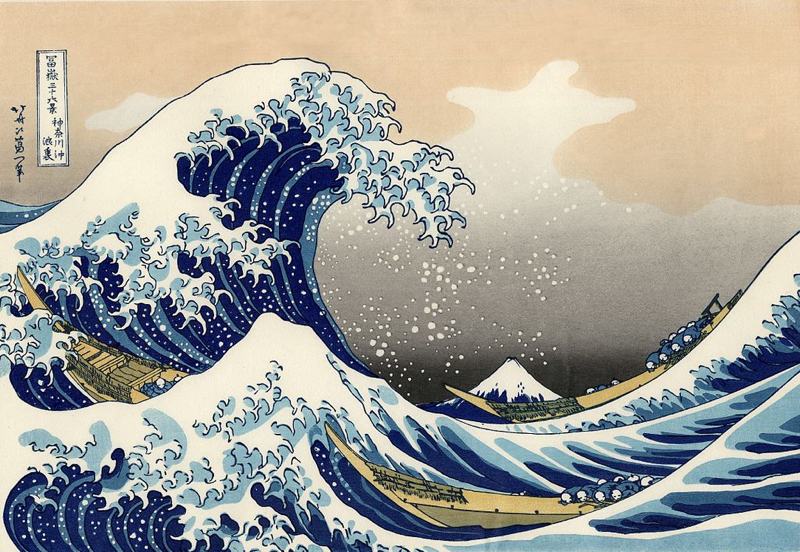

Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e 浮世絵 is a genre of Japanese woodblock prints and paintings. Their production began in the Edo era, when Japan began urbanization. They primarily depict beautiful women, famous theater actors, sumo wrestlers, and traditional Japanese folk tales. Rather than have a single artist create their own carvings and prints, production of ukiyo-e was often divided into three parts.

- A carver who would create the woodblock.

- A printer would ink the woodblock and press the image onto paper.

- A publisher would finance the operation and distribute the finished products.

Modern ukiyo-e are usually not produced in the traditional woodblock and carving method. Rather they incorporate modern techniques like screen printing, etching, mezzotint, and other multimedia platforms.

Despite the evolution of ukiyo-e production, there is an artist in Japan who continues to use the traditional carving and printing methods. Originally from Toronto, David Bull first became interested in ukiyo-e when he visited a local gallery featuring woodblock prints. He became intrigued with the production process, and moved to Japan in 1986 with his Japanese wife. Bull is self-taught, and learned by studying the works of great ukiyo-e artists from the Edo era.

"My teachers were the long-gone workers from 100 years ago," Bull said, "and I had to learn everything from scratch."

Although ukiyo-e production is traditionally done by three people, Bull does everything. He designs, carves, prints, and publishes his own works. His works are made in series, often taking years to complete. His first series, Hyakunin Isshu (one hundred poems from one hundred poets), consists of 100 prints depicting classical Japanese poets, and took him ten years to complete, producing ten prints per year. In recent years, Bull has begun teaching young aspiring artists his techniques in addition to his solo craftsmanship, and operates with others as the Ukiyo-e Heroes production team.

Traditional Jobs in Japan Aren't Only for the Japanese

Japan has a reputation for being a very insular country, one where a foreigner can never quite feel like they fit in. Some people say that only a native-born Japanese can adequately understand the nuances of Japanese traditions. However, history has proven that you don't have to be born Japanese to appreciate, and even master, some of Japan's most ancient and treasured cultural phenomena. Foreigners from other Asian countries and even Westerners who spent the bulk of their lives ignorant of Japanese culture have found their way into Japanese society, and continue to flourish today. Something that is traditionally Japanese doesn't require a Japanese person to keep it authentic.