Can someone tell me what year it is? 2014? Wait. What system are you using? It’s obviously Heisei 26 right now, the 26th year of the current emperor’s reign. Sure, you could use the Gregorian calendar, but that’s not the way Japan does it. The native Japanese calendar is utilized, nearly interchangeably, with our Western one. In fact, the native Japanese calendar, or “the nengō naming system”, is the official dating system still used in Japan today. The Japanese government and most businesses continue to date things using this method.

We now know that the date is Heisei 26 because it’s the current emperor’s 26th year in power. But, I bet you’ve heard of some of the other era names too. Showa? Meiji? Taisho? Genroku? Anything sound familiar here? If not, that’s fine – you’ll be getting plenty of exposure to them from here on out.

Made in China

Like many other conventions in Japan, the nengō system of naming the periods by the reigns of emperors was imported from China. Originally, this was one of the many ways Japan tried to legitimize themselves in the eyes of the various Chinese dynasties. There was one big difference, though. In Japan, there has only been one single “dynasty.” The imperial rule has arguably been the same since the beginning of their history. In China, however, there is something called the “Mandate of Heaven,” which basically says that if there is an unjust guy on the throne, the heavens will make sure he is overthrown and a better ruler can take over. Smart of the Japanese imperial family to leave this little tidbit out of the Japanese emperor rulebook.

While Japan didn’t really understand the concept of different families ruling, they did understand the need to legitimize the succession of the imperial heirs. Since the start of recorded history there have been numerous methods of keeping the same bloodline going. From inter-marriage, female empresses, and the inclusion of distant relatives, the Japanese imperial family has worked very hard over centuries to continue their only dynasty. With all of the work they were doing to keep the same family at the top, creating a distraction from unpleasant events seemed like a good solution.

Pretty Names Made People Forget the Bad Stuff

After China’s Han Dynasty (205BC – 220AD), the Han Emperor began attaching names onto the years in which emperors ruled. In English, we call these attachments “reign titles”. These reign titles were not the names of the emperors, but rather descriptors of what the emperors wanted their reign to be associated with, such as Jianyuan (establishing the first) or Jianzhongjingguo (establishing middle, peaceful country). By 645AD Japan’s Emperor Kōtoku adopted this custom. Japan called their reign titles nengō 年号. For anyone who is confused by that kanji, don’t think of the 号 as a number, think of it as a name. That will clear things up for you.

The very first nengō was Taika 大化 which started in 645AD with Emperor Kōtoku. So we would call 648AD the “third year of Taika,” rather than the “third year of Kōtoku.” This is the same as calling 1989 the “first year of Heisei” (or the last year of Showa if it’s early January).

Emperors in Japan would give these names to the periods of their reign and they were not limited to just one. Some, like Emperor Go-Daigo had as many as eight different reign titles. Some of them would even have more than one in a single year. Nengō were meant to signify a change, new beginnings, and good things. Although this is a wonderfully artistic way to do things, for someone who is unfamiliar with these types of naming conventions, it can make things overly complicated.

For those wondering what kind of event would cause one of these names to change, it could literally be anything.

Many of these nengō are not so important that you will instantly know when or who they are referring to. However, if you are studying a certain period, you may notice that a particular name is used frequently in reference to it. For example, maybe you’re looking up the forty-seven Ronin (Try and [stay away from the Keanu Reeves one) and you keep seeing Genroku 元禄 everywhere.

What is that anyway? Well Genroku was the nengō Emperor Higashiyama gave to the first years of his reign. So from 1688 to 1704, we call it the Genroku Period (元禄時代). The first year to every new emperor’s rule would get a name and this emperor was certainly optimistic about the start of his. Genroku basically means “the origin of happiness.”

However, even with such a nice name picked out, the Genroku period was plagued with huge fires and violence. Finally, after the Great Genroku Earthquake, the reign title was changed to Hōei 宝永 which means “eternally prosperous.” This was the new beginning the people of Japan needed. This was going to be a great, successful time! (Then there was another earthquake less than four years later.)

Luckily for us, emperors were limited to one name after the Meiji restoration, which is why, although there were 63 years in the Showa period, we only have one name for it. Also, notice that the emperor’s posthumous name and the nengō for their period are the same. So if you know who the Taishō Emperor (大正天皇) is, you know his nengō was Taisho 大正. It’s certainly much easier than it once was.

Made up of Heaven and Earth

Now that you know all about how the emperors name things, let’s complicate it!

Once more we have something that came from China – but this time it was adopted completely, no extra complications. That’s good, right? We call it the “Sexagenary Cycle,” and it’s made up of the “Ten Heavenly Stems” and the “Twelve Earthly Branches,” which you can see in the picture above. Here is a list of all the on’yomi and kun’yomi readings, respectively:

Heavenly Stems:

| Kanji | On'yomi | Kun'yomi |

|---|---|---|

| 甲 | kō | kinoe |

| 乙 | otsu | kinoto |

| 丙 | hei | hinoe |

| 丁 | tei | hinoto |

| 戊 | bo | tsuchinoe |

| 己 | ki | tsuchinoto |

| 庚 | kō | kanoe |

| 辛 | shin | kanoto |

| 壬 | jin | mizunoe |

| 癸 | ki | mizunoto |

Earthly Branches:

| Kanji | On'yomi | Kun'yomi |

|---|---|---|

| 子 | shi | ne |

| 丑 | chū | ushi |

| 寅 | in | tora |

| 卯 | bō | u |

| 辰 | shin | tatsu |

| 巳 | shi | mi |

| 午 | go | uma |

| 未 | mi (or) bi | hitsuji |

| 申 | shin | saru |

| 酉 | yū | tori |

| 戌 | jutsu | inu |

| 亥 | gai | i |

If the Earthly Branches look familiar to you, it is because they are the same characters used for the Chinese Zodiac and they are also used in the solar calendar in Japan – but let’s not get distracted by that right now.

The order they are in is set (don’t mix them up!) and there are sixty possible combinations of Heavenly Stem + Earthly Branch. The first combination is 甲子, then it goes 乙丑, 丙寅, 丁卯, and so on taking the next from each respective row. When you reach the end of the Heavenly stems, just go back to the beginning and you end up with 甲戌, until you have all 60 and end up back at the start. Each one of these combinations is a cycle.

If you’re wondering how to read them, they can be with either the on’yomi or the kun’yomi, so no worries. Usually how you say it only depends on context, but you shouldn’t sound super weird either way. If you want to say 2014 you can choose to say kōgo or kinoeuma for 甲午.

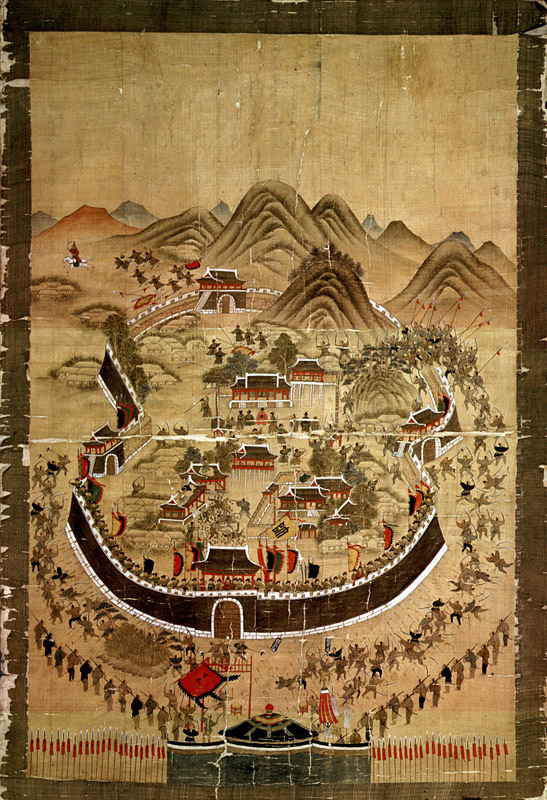

The great thing about these cycles is that China, Korea, and Japan all use it the same way, meaning that no matter where you go in these three countries it should remain consistent, unlike the nengō, which are different based on which country you’re in. This is important because this system is used all throughout East Asia to name important events in history. It also can be used to compare nengō dated events and the sexagenary cycle. For example, let’s look at the Japanese invasions of Korea:

In Korea the first invasion is called the Imjin Waeran. Imjin 壬辰 being the sexagenary cycle year of 1592, the year it began. This same event is called the Bunroku no eki 文禄の役 in Japan. Bunroku 文禄 was the nengō that started under Emperor Go-Yōzei that same year.

In modern times these two systems are still being used. Postcards, art, signs, and really anything that might need a date on it. They can be used to date something without having to use any numerals at all, and gives whatever they’re on an artsy, old-timey feel.

Here is an example: it is currently 2014, which means it’s the 26th year of Heisei, or 平成26. But, by combining the nengō and the cycle name, it can be written as 平成甲午. You may pick out a postcard at the top of Mt. Fuji and notice those characters somewhere on the front of the picture. Years from now, when your grandkids ask when you were there, you can look at at that date and say, “Ah! 2014!”

Modern Calculators Make It All Easier

The cycles are also assigned to months and days but they come up much less often than they do with years. There is a mathematical calculation to find out what year is assigned to what cycle, but remember, Japan did not start using the solar calendar until the Meiji period, so if you decide to do some math you need to base it before or after Meiji.

Here is an example. To determine the sign for 1977 you will follow this guide:

- 1977 – 3 = 1974

- 1974 ÷ 60 = 32 (If you end up with a fraction, simply drop it.)

- 1974 – (60 x 32) = 54

- The 54th pairing in the Sexagenary cycle will then give you 丁巳. That’s 1977.

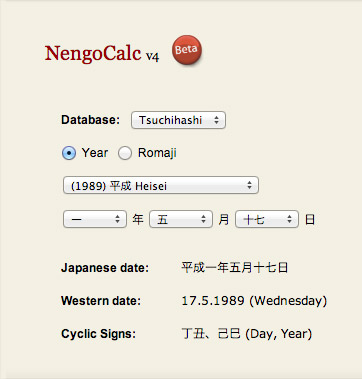

If you’re math-shy like I am, you can always search online to see what the date you want to know was called. If you want an even easier method you can use this nifty calculator called NengoCalc.

I know, I know. It says nengō, not cycles, but it can help with both! This tool can help you find out the nengō for any year from 598 to 2008. Not only will it provide you with the Japanese and Western dates, but it will also give you the sexagenary cycle year and day too. It even tells you what day of the week it was. It may take a bit of trial and error to get the hang of it, but it’s a great way to find the names you need in a hurry.

You never know when being familiar with these naming systems will come in handy. You may encounter a beautiful painting when you’re studying abroad in Japan. You can see the artists signature in red in the corner, but there are no visible dates. How do you know which Tanaka painted this possible masterpiece? Well odds are they have the nengō and the cycle on there instead. This is the case with some of the postcards you see at tourist spots today. If you’re in Japan around New Year’s, you may also see something like this:

This lists the year with both the nengō and the sexagenary cycle: 平成二十五年癸巳歳. More simply, this was 2013. You may also notice the earthly branch 巳, being from the Chinese Zodiac, also tells us that this is the year of the snake. (Thus, the flowery snake in the picture.)

The government in Japan also still uses this system of dating on official paperwork, though it is less common that you would be able to see this in your day to day life.

While it’d take a lot of time, sweat, and effort to memorize all these nengō and sexagenary combinations, at least you now know how to look them up, convert them, and seem like you know what’s going on. Who knows? It may just come in handy some day!

Days of the Week

So now that you know about the bigger picture (years are pretty big units of time measurement), let's move onto something a bit smaller. The Gregorian system is the internationally accepted calendar system and Japan officially adopted a variant of the Gregorian calendar in 1873. Before that, Japan used a seven day calendar system lunisolar system for almost 1200 years. And then when they moved over they carried some things from the old calendar with them.

Have you ever thought about the names of the week? The naming scheme comes from the combination of the Chinese philosophies of yin-yang and the five Taoist elements.

| Day | Japanese | Element |

|---|---|---|

| Sunday | 日曜日 | Sun (Yang) |

| Monday | 月曜日 | Moon (Yin) |

| Tuesday | 火曜日 | Fire |

| Wednesday | 水曜日 | Water |

| Thursday | 木曜日 | Wood |

| Friday | 金曜日 | Gold (Metal) |

| Saturday | 土曜日 | Earth |

Algebraic, right?

But wait! Did you know that along with the seven-day calendar systems used in the last 1400 years, there was another system used by the Japanese? (And other Asian countries too!)

The Rokuyō Calendar

Rokuyō 六曜 (meaning "six weekday") is a Japanese calendar that marks "auspicious" days. Auspicious basically means that a day will be really great. And of course it also marks days that won't be so great, because everyone knows ALL days can't be the best day ever.

The Rokuyō calendar we use today is a variation of the original that came from China around the 14th century. It is made up of six cycling days that are based on astrology and each day determines the level of auspiciousness. In other words, it’s a fortune telling calendar system!

So here is the order and level of goodness each day has:

| Japanese | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 先勝 | Good luck in the morning. Bad luck in the afternoon. |

| 友引 | Good luck all day except noon. |

| 先負 | Bad luck in the morning. Good luck in the afternoon. |

| 仏滅 | Bad luck for the entire day. |

| 大安 | Good luck for the entire day. |

| 赤口 | Bad luck all day except at noon. |

These days cycle in order through each Gregorian month. That means January 1st starts out as Senshō 先勝, January 2nd is Tomobiki 友引, January 3rd is Senbu 先負, and so on.

But how serious is this good luck/bad luck stuff to Japanese people?

It really depends on how old you are. The older generation may take them more seriously, while young kids just glance at which day it is on their phones in the morning. Kind of like how some people really get into horoscopes and others know they exist, but don't really pay attention.

We know some people care because about three times as many weddings are held on Taian 大安 days than on Butsumetsu 仏滅 days. Due to this huge difference in planning, rates for weddings held on Butsumetsu days are waaay cheaper than any others.

If you are born on a Taian day that's supposed to be really great. And with advances in modern medicine, many parents opt to induce labor if a desirable day is near or to delay the birth if the day falls under a Butsumetsu day (or so people say).

But don't go thinking Butsumetsu is a day where you're supposed to hide in your home doing nothing.

The kanji for Tomobiki 友引 literally translates to “pulling a friend.” Due to it’s name, it is considered bad luck to schedule any funerals on these days. What kind of dead friend would pull you to the death realm, anyway? Crematoriums are typically closed on this day. Good to know.

Also another good thing to know: some Shinto shrines close on Butsumetsu. If you ever plan on visiting one, be sure they are open on the day you are visiting!

This site is great for finding out which Rokuyo day it is in English and what that means for you.

The Zodiac

So we've looked at years and days, what's left? Hours! Or at least an idea of time smaller than a day. You see, before there was 1 o'clock, 2 o'clock, 3 o'clock there was the hour of the rooster! And where we have AM and PM there were Day and Night hours. Let's take a look.

The Basics of the Zodiac Clock

The fact that the traditional Japanese clock They’re known as wadokei 和時計 was based on the Chinese zodiac is probably the least surprising thing about it. We’ve written before about how the Chinese zodiac is so influential in Japan that it caused people to stop makin’ babies (at least for a year).

The clock is divided into two parts: one for daytime and one for nighttime. Each “hour” is associated with an animal from the zodiac. The daytime hours start at sunrise, with noon at the hour of the horse.

Day Hours

| Zodiac Sign | Zodiac Symbol | Current Time |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit | 卯 | 5AM - 7AM |

| Dragon | 辰 | 7AM - 9AM |

| Snake | 巳 | 9AM - 11AM |

| Horse | 午 | 11AM - 1PM |

| Ram | 未 | 1PM - 3PM |

| Monkey | 申 | 3PM - 5PM |

Notice how these aren't just for one hour, they're three.

Anything else? That's right, these are the same symbols you've seen before in the sexagenary cycles. The zodiac and the Earthly branches use the same kanji! Talk about full circle. Just like clocks. And time. Boom!

The night clock goes pretty much the same way as the day clock, but with different zodiac animals. It begins at sundown, with midnight at the hour of the rat.

Night Hours

| Zodiac Sign | Zodiac Symbol | Current Time |

|---|---|---|

| Rooster | 酉 | 5PM - 7PM |

| Dog | 戌 | 7PM - 9PM |

| Boar | 亥 | 9PM - 11PM |

| Rat | 子 | 11PM - 1AM |

| Ox | 丑 | 1AM - 3AM |

| Tiger | 寅 | 3AM - 5AM |

Over time, and mostly because of Western influences, this way of telling time fell out of favor. Which is pretty much the same thing that happened to nengo. Though you'll still run into both of them every now and then.

Hopefully now you know a lot more about Japanese time telling than you did before! Good luck and spend the rest of the time you have wisely.