Shigeru Mizuki is probably the most famous manga author that’s almost unknown in the English-speaking world. Now 92 years old and still working, he’s most famous for creating GeGeGe no Kitaro, about a one-eyed yokai boy named Kitaro. With a long-running manga and anime series and several movies, Kitaro revived interest in traditional yokai stories as well as making his original yokai creatures part of the traditional.

While probably every living Japanese person would recognize his name, his work has barely been translated into English until recently. Maybe that’s partly because Kitaro is so dependent on Japanese cultural references, unlike comics about, say, robots and outer space. Fortunately, this is finally being remedied in a big way by publisher Drawn and Quarterly. They’ve put out a number of fat volumes of Mizuki’s work recently, including a collection of Kitaro and NonNonBa, an autobiographical volume about his childhood and the old woman who first told him yokai tales.

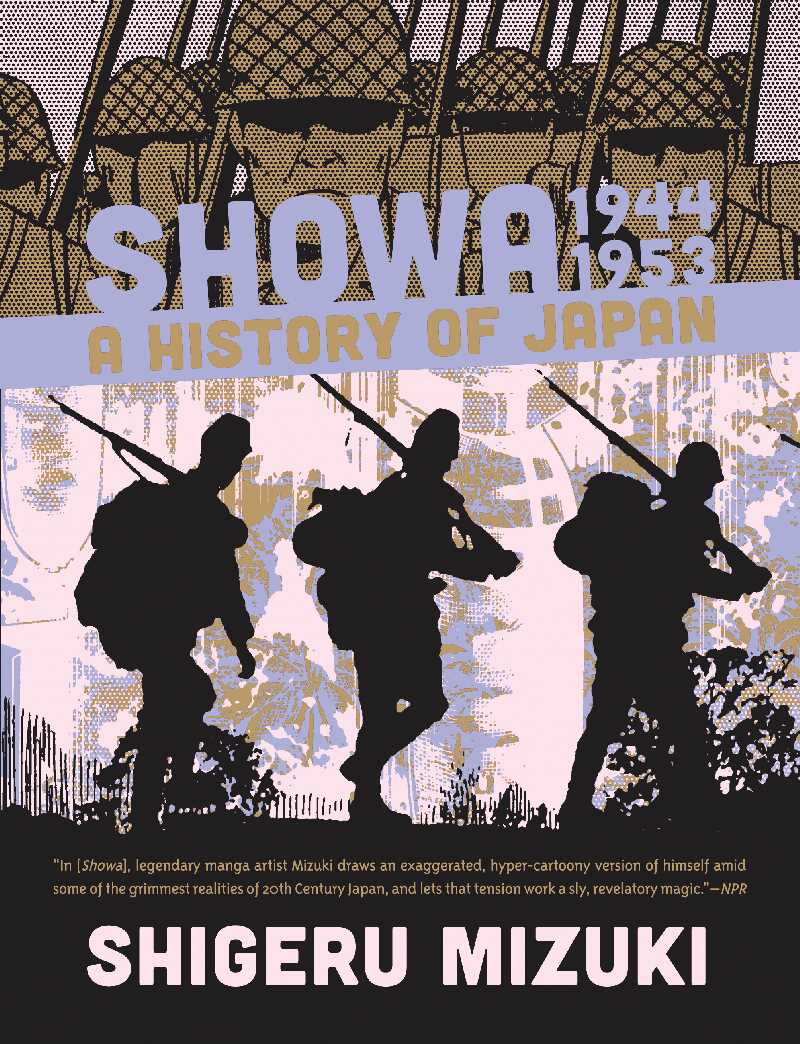

There’s another side to Mizuki’s work and life, though. As a soldier in World War II, he lost an arm in a bombing raid, and he’s written serious, realistic manga about the war. Showa: A History of Japan is one of these – or actually, four of these, at least in translation. The third volume covering the years 1944-1953 was just published, and the fourth volume is due in April of next year.

“Showa” is the name given the period of the reign of Emperor Hirohito, which began in 1926 and ended in 1989. The first book in the series opens with a prologue that makes it clear that this isn’t going to be all fun and games. It’s about the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 and the ensuing run on the banks. I’m willing to bet that banking crises are not the sort of thing the average American fan expects as a subject in manga. If you’re going to read this one, start adjusting your expectations.

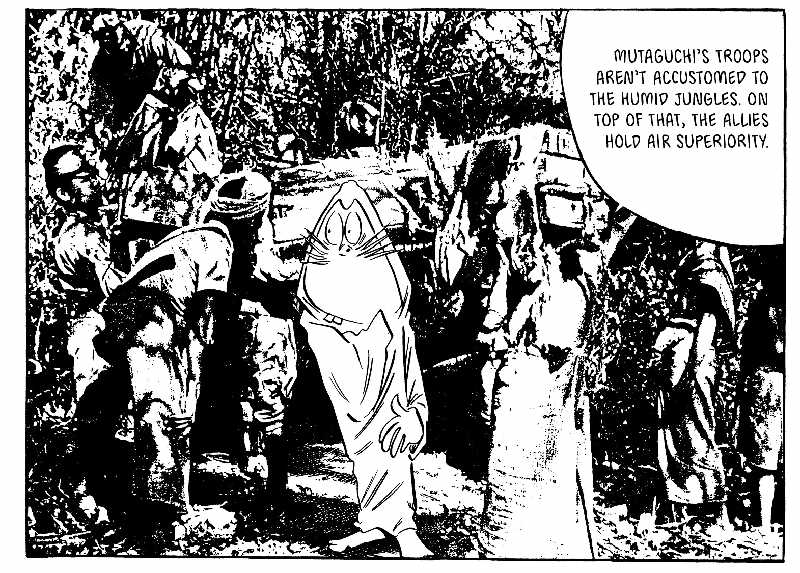

The next chapter is then much more lighthearted, about Mizuki as a very small boy who is foolish enough to eat all the gold paint off a wooden ball. This wide swing in subject matter sets the tone too, because maybe the most interesting thing about these books is how they combine events and details that don’t obviously fit together. The backgrounds are drawn in realistic detail, from streetscapes to battleships to the jungles where he fought in the war, as are some of the historic figures, while the main characters are cartoony. There are vivid stories of his life from school to work to war, and there’s also explanatory narration that could come right out of a history textbook.

And if you’re completely unfamiliar with Mizuki’s work, the most mind-bending example of these combinations will be the one that starts on page 93 of the first volume: a strange cartoon fellow with a pointy head and whiskers appears and explains the details of a new censorship law. As he introduces himself a few pages later, this is Nezumi Otoko (Rat Man), a character from Kitaro. The footnote (yes, there are footnotes by both Mizuki and the translator) explains Nezumi Otoko’s role by asking us to imagine that Walt Disney had written a history of World War II and used Donald Duck as a narrator. Translator Zack Davisson knows his stuff, so I’m assuming that the rather surreal picture that it puts in my mind is exactly what Mizuki intended. The war was clearly a surreal experience at times, so if Nezumi’s appearance puts the reader off-balance, it’s only appropriate.

In the Kitaro stories Nezumi Otoko is generally a troublemaker, which makes him an interesting choice as a narrator. Mizuki seems like a troublemaker at heart himself – there is nowhere in the autobiographical parts of this series where he’s content to just follow the rules and do what’s expected. So if he was going to pick a character to convey his opinions about war and politics, it makes sense it’s one like Nezumi Otoko.

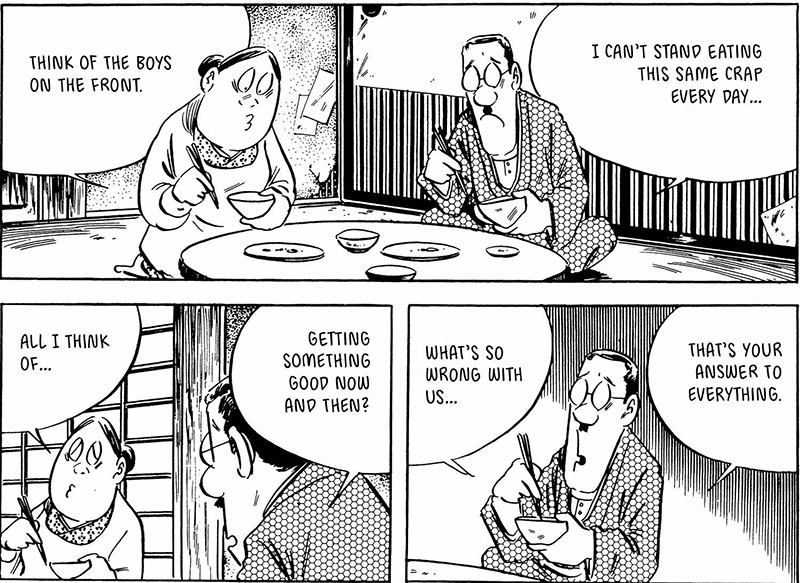

There are layers within layers here, so like with any work as complex as this, you can read it in many ways. The ideal reader for this book needs to be interested in just about everything about life – comics, politics, economics, social history – and ideally needs to enjoy combat scenes and strategy, a taste I’ve never been able to acquire. But there’s also plenty in it for the reader like me, who was inclined to peek ahead to see when I’d get the next chapter about the day-to-day life of Mizuki and his family in wartime.

Those were the details that kept me fascinated: Mizuki getting sent to the front because he hated playing the bugle and asked for a transfer out of the bugle corps. His mother swearing to the gods that she’ll give up octopus, her favorite food, if only he comes home safely. The guy who spent his rice money buying a book at a time when food was rationed. Mizuki coming home after the war and studying art despite the terrible state of the economy at a school that had to rent out some of its classrooms to a noodle factory to afford to stay in business.

Showa: A History of Japan – The Verdict

My final verdict? On the one hand, Mizuki Shigeru is a giant of Japanese culture, a living legend, writing about his life and the major historical events of the twentieth century, and who am I to pass judgment on such a thing? On the other, not all serious masterpieces of culture are exactly enjoyable to read, which I think is a fair question.

So: With each volume coming in at over 500 pages, even if you only love half of it, you get your money’s worth. It’ll definitely give you something weighty (in both senses) to hand to anyone who says you’re wasting your time reading comics. And finally, if I’m going to learn the sort of history that’s about which politician said what and how this or that general made some strategic decision, it’s a lot easier to take from Nezumi Otoko than from a textbook.

Kristen’s Review

I’m going to start by saying this series is extremely good. But getting through it felt like more of a chore than an enjoyable way to spend my free time. The sections about Mizuki’s life and past were very interesting. I would soar through them, totally absorbed, only to be dumped into realistic war backdrops with lists of historical figures and facts that honestly couldn’t hold my attention. Every single page had an endnote, which would send me flipping to the back of the book for a short paragraph, flip back, read half a page, and then back to the notes section again. My hand cramped more than once.

Michael’s Review

I love history and Mizuki’s manga, so reading this series was a joy. I had never read such a full account of Japan’s side of Word War II, let alone the rest of 20th Century that followed. The history parts were slow, and I didn’t always enjoy the use of photos mixed with the art, but I’m glad I read all of it—especially the autobiographical pieces. Mizuki was an incredibly interesting person, and his life is inspirational. If you like Japanese history and manga, this was was made for you.