When you refer to yourself in English, you use "I," "me," "myself," and… probably not much else. But what about in Japanese? Some scholars say that, if you count all its regional differences and euphonic changes1, Japan has more first-person pronouns than any other language.

Japanese pronouns convey a variety of subtexts, including formality level, gender identity, social hierarchy, and psychological distance.

Why so many? Japanese pronouns convey a variety of subtexts, including formality level, gender identity, social hierarchy, and psychological distance.

Most native speakers don't stick with one pronoun for their whole life, or even for their whole day. They switch pronouns depending on where, when, and to whom they're talking, as well as how they want to present themselves. Although people usually have their own set of go-to pronouns for different purposes, this can change from time to time — they might grow out of one and into another, or spice things up with a trendy new first-person pronoun. (The nuances around first-person pronouns are constantly changing these days.)

How you refer to yourself in a given situation helps to communicate your personality. Do you want to sound polite? Modest? Cute? Do you want to sound like your favorite samurai anime character? The choice is yours — and this article will help you make a more personal choice. Since there are many regional differences in the use of Japanese first-person pronouns, this article covers the way people use them in the Tokyo area, unless otherwise specified.

- Common First-Person Pronouns

- Pluralizing Suffixes

- Uncommon Pronouns (Used in Real-Life)

- WATASHI Am Glad You Made It This Far!

Before you read on, consider listening to this series of podcast episodes we made on Japanese first-person pronouns. They give you a good overview of 私, 僕, うち, and 俺, which are arguably the most important to know. And as always, we dig into a few details of each of these that evolve naturally in the conversation, so to get the full picture we recommend reading the article and listening to the podcast. Following requests from readers, we also made an episode about how stereotypically-male first-person pronouns are used by female speakers. If you like what you hear, why not subscribe to the podcast?

Common First-Person Pronouns

Even if you're just starting to learn Japanese, you may already know and use the most common first-person pronouns. But each one contains nuances that most textbooks don't cover, so let's go over the specifics for each one.

私 (わたし)

You're probably familiar with わたし already, as most textbooks teach this one right off the bat. It's flexible, and relatively neutral in terms of gender expression and formality. If you're a beginner, or not yet confident using other first-person pronouns, わたし is a fine choice.

What makes わたし so interesting is that it communicates different gender nuances depending on the formality of the situation. For example, in casual situations it has a definite feminine feel to it. In formal situations, it is more gender-neutral. Many adult male and female speakers use it in professional settings, such as interactions with clients.

Let's take a look at some examples to see what this actually means. These examples can all be translated as "me too" in English.

- わたしも!

- Me too! (casual)

This example is a female speaker using わたし in a casual setting. In this sentence, the absence of the politeness marker です suggests that this is a casual speech style. In casual situations, わたし expresses femininity, as わたし is used by many female speakers (especially adult women).

- わたしも!

- Me too! (casual)

This example is also casual, but this time recorded by a male speaker. Since わたし is not so commonly used by male speakers outside of formal situations, this example can sound like the speaker is intending to sound feminine, or extra polite.

In formal situations, when you say something like 私もです, it doesn't carry a particular gender nuance. It's widely used regardless of gender, especially in professional settings.

私 (わたくし)

Using the same kanji, わたくし is a super-polite version of わたし. This "alternate" reading of 私 is actually the original reading. It's reserved only for very formal situations — I wouldn't use it outside of deadly serious, formal occasions.

- わたくしもです!

- Me too! (formal)

- わたくしもです!

- Me too! (formal)

You'll often hear わたくし in official announcements: for example, when politicians make campaign promises.

わたくし can sound rather stiff in semi-formal situations. I was taught to use わたくし at a business etiquette seminar I took for my first job right out of college, and while I agree it's the proper first-person pronoun for conservative business scenarios or very serious situations, I personally didn't get to use it much, because I was in the creative industry, which is more casual.

- 私のせいでご迷惑をおかけし、申し訳ございませんでした。

- I sincerely apologize to you for the trouble I caused.

Beyond the business world, you'll often hear わたくし in official announcements: for example, when politicians make campaign promises, or when celebrities announce a wedding or apologize for a scandal.

- 私、トーフグ党のコウイチは、皆様の平和を誓います。

- I, Koichi from the Tofugu Party, promise peace for you all.

Because of its high level of formality, わたくし also carries a somewhat elegant and sophisticated feel. You may see it being used in fiction by characters like princesses and servants.

あたし

あたし is a common, shortened, slang form of 私 used only in casual settings. Because children have trouble pronouncing "w" sounds, あたし carries an endearing, childish quality. The difference in pronunciation between あたし and わたし is subtle and may be hard to catch when spoken, but you'll see it a lot in pop culture writing and on social media.

- あたしも!

- Me too!

僕 (ぼく)

Because the word originally meant "slave," the use of 僕 as a pronoun was once used to show humility. But male academics claimed it in the Meiji period, and the pronoun took on an earnest, polite, and cultured connotation, in a similar way to the second-person pronoun, 君.

The main user demographic of 僕 is male speakers both young and old, and lately girls too, thanks to the influence of anime. Though it is still associated with male gender, the masculine nuance it carries is a lot weaker, and it has a more gentle feel than the first-pronoun 俺, which we'll look at next.

- 僕の好きな作家は、芥川龍之介です。

- My favorite novelist is Akutagawa Ryūnosuke.

- 僕は先生に賛成します。

- I agree with Teacher.

Personally, I've heard 僕 used in situations from the casual to the semi-formal range, and it feels like a comparatively modest and polite pronoun to me. Even if they primarily use 俺, many of my male friends would use 僕 as a kind of "good-boy mask" when talking to bosses or people they don't know well. Technically, 僕 is usually used to address people with equal or lower status, and 私 is more suitable in very formal situations such as conservative business communication. However, in my opinion, 僕 is appropriate in semi-formal situations, especially if you don't want to keep the listener at too much of a distance. Assuming it's not a conservative environment, you might use 僕 when speaking with a member of the same social group, or your sensei, senpai, or boss.

僕 is also traditionally the first first-person pronoun that Japanese boys are taught. Despite being a common first-person pronoun choice for adult men, it can have certain connotations of immaturity and dependence. For example, a typical "mama's boy" in movies and TV shows will often refer to himself as 僕.

僕 for Little Boys

The fact that 僕 is stereotypically used by boys has led to an additional use as a second person pronoun. It's as if you're referring to a boy from his perspective. Imagine you meet a young boy who looks lost. You might say:

- 僕、迷子?

- Are you lost?

This is an affectionate way to refer to a little boy you don't know — it's also the typical way to treat a little boy like a little boy! Note that your use of the pronoun may offend a more mature boy who doesn't want to be treated like a child. A safe age range to use 僕 would be up to five years old, though I admit I don't know much about cool kids these days!

俺 (おれ)

俺 is another common first-person pronoun with masculinity. 俺 is quite casual, and sounds "manly" and less gentle than 僕.

When I was growing up, most boys transitioned from 僕 to 俺 in early elementary school, but these days boys seem to be using it as early as three years old. Most of my male friends in their twenties and thirties use 俺 as their primary first-person pronoun when talking to people close to them.

- 俺、ちょっとコンビニ行って来る。

- I'm going to the convenience store real quick.

While I still hear 俺 used in keigo sentences, some people — especially those at the more conservative end of the spectrum — might consider it inappropriate in formal situations. For those situations, you can consider switching 俺 to other pronouns that carry more humbleness, such as 私, 僕, or 自分, as a backup.

As a heads-up for Japanese learners, be aware that using 俺 could make you sound inadvertently cocky. 俺 can also be tricky to master for second-language learners, because it doesn't sound natural unless you speak Japanese really fluidly and effortlessly. 俺 can sound awkward when other elements in a sentence don't match the aggressiveness and masculinity of 俺. Compare the two sentences below:

- 僕のプリンを食べたのは誰?

- Who ate my pudding?

- 俺のプリン食ったの誰だよ?

- Who the heck ate my pudding?!

Pronouns aside, other words in these sentences completely change the degree of masculinity they convey: 食う is a gruffer way of saying 食べる, and the inclusion or omission of は and だよ increases or reduces the nuance of aggressiveness.

When I was growing up, most boys transitioned from 僕 to 俺 in early elementary school, but these days boys seem to be using it as early as three years old.

These details matter when trying to match your tone to 俺. If we switched 僕 and 俺, the sentences wouldn't sound as natural.

Are you starting to see why it isn't so easy to master 俺? I have male, Japanese-learning friends who are pretty fluent, but when I hear them use 俺 in conversation, it sounds a bit forced sometimes. Bottom line? I would say, if you're confidently fluent in Japanese — especially "manly" speech — and you think your personality fits the 俺 vibe, go for it! If not, just keep in mind that it's not as easy as simply replacing other first-person pronouns with 俺.

うち

Over the past thirty years, this casual first-person pronoun from Kansai has become popular with young women across Japan thanks to anime, gyaru, and the region's comedy culture. I myself used it often with my friends and family until I was in high school, and it still seems to be a popular pronoun for women around that age.

Although わたし tends to overshadow うち as the standard pronoun that women use in casual settings, うち is gaining ground, especially among elementary to college students. It's taking on the role that 俺 has for many male speakers — a relaxed pronoun that you can use in a carefree way with friends. Some research shows that うち is the most popular option for young female speakers these days, as many find わたし a little too standoffish to use with their buddies.

Now that I've settled down and become a mature adult, I use わたし most of the time. After my うち phase, I switched to わたし when I started working because I felt like business etiquette required it. However, I still use うち from time to time when I'm around people I know well.

I especially use うちら (we) as my plural form to avoid saying わたしたち, which is long and hard to say. And most importantly, as the word's origin 内, meaning "inside" suggests, it carries a sort of feeling of unity, as if you and the people you're using うち or うちら with are inside a tight community or group of people. In that sense, it's not at all rare to see うちら being used regardless of gender to express friendliness or affection.

- うち、フラフープするのが好きじゃん?

- So, I like hula-hooping, right?

- この線のこっち側は、うちらのスペースだよ。

- This side of the line is our space.

Be aware that, just like 俺, using うち may give some people a bad impression of you because it's slangy. Some might also feel that it sounds strange when used outside of specific dialects. But as a former うち user myself, I found it nice to have an option besides わたし. Between close friends, it creates feelings of fondness and unity.

自分

自分 (じぶん) is the very versatile Japanese word for "self": you can use it as "myself," "yourself," "herself," "himself," or anyone's-self!

- 私は、自分で料理します。

- I cook by myself.

自分 is also used as a first-person pronoun in hierarchical systems such as sports teams and the military. Though traditionally not considered appropriate in most formal settings, it does show humility and respect to the person you're talking to. It's also a popular alternative in formal situations among young 俺 users who feel that 私 and 僕 don't suit them.

- 自分は、トーフグ基地から来ました、コウイチと申します。

- I am Koichi, from the Tofugu Base.

- 今日の練習は、自分がキャッチャーやります。

- I'll be a catcher for today's practice.

Even though it's often associated with a certain masculinity because of its use in the athletic and military communities, as a female speaker I occasionally use 自分 as first-person pronoun when talking to my senpai, boss, or another authority figure. Because it's not traditionally considered "a pronoun for men," and because I use it all the time as a reflexive pronoun meaning "myself," I find it easy to use 自分 as a first-person pronoun, and I don't have the same sense that I might be judged for it, compared to stereotypically masculine pronouns like 僕 or 俺. Particularly when I was working in a male-only environment in Tokyo, 自分 was my top choice if I didn't want to express any femininity in the way I spoke.

Since it's relatively gender-neutral, it's also common in the LGBTQ community. For example, research conducted at lesbian bars in Tokyo shows that it was a popular choice among those who self-identified as onabe. For more about the use of first-person pronouns in LGBTQ community, check out our article Beyond the Binary: A Queer Take on Gendered Japanese.

Your First Name (or Nickname)

Using your own name or nickname (with or without ちゃん/君) as a first-person pronoun is common for little children. It's what their parents and other adults call them and thus how they recognize themselves, so it's only natural that they use their names when they start talking, but children generally transition to first-person pronouns as they grow and learn the world.

Personally, I grew out of it as many others do, but still used my own name to refer to myself at home. I had another reason to do so: as a younger sibling, it bugged me when my parents or grandparents accidentally called me by my sister's name. And it still bugs me, because I now live far from my family and my sister gets to talk to them more often, so it happens even more often. For that reason, I still use my name as a first-person pronoun — mostly when talking to my grandmothers, who are more likely to mix up our names.

- かなえの手紙届いた?

- Has my letter been delivered yet?

I'm not an exception either. Research shows that girls stick with their names longer than boys, and some use them into adulthood. More specifically, quite a few women in their twenties use their names as first-person pronouns with their families.

Some of my friends certainly used their names as pronouns until we were in junior high. But while I never call myself "Kanae" outside of family interactions anymore, plenty of people (who aren't that young anymore) do. It's a controversial topic in Japan, and many people see it as childish and show-offy. Some people hate it! Many adults who openly use their names for themselves happen to be female and are often seen as ぶりっ子, or girls who try to be cute to make themselves more popular with men.

Calling yourself by your own name also expresses a certain self-assertiveness and ego, and some celebrities have used it as part of a sort of self-branding.

There is an exception though. In Okinawa, it's more culturally acceptable for women to use their own names as first-person pronouns. I never knew this until I made friends with women from Okinawa. I found it a little odd at first, but they said it so naturally (and it didn't seem like they were trying to be ぶりっ子) that I soon got used to it. Then I found out that this is a regional cultural difference — suddenly, it all made sense.

The bottom line? Keep in mind that you may be judged or seen as immature by others, especially outside of Okinawa, if you call yourself by your name. There are cases in which it's endearing, but only if it fits in with the speaker's natural, spoiled, goofy, or ぶりっ子 personality.

Family and Social Roles

Next up are pronouns with limited usage, of which my family is a perfect example: everyone refers to themselves using their role in the family. My mother uses お母さん (Mom), my father uses お父さん (Dad), my older sister uses お姉ちゃん (older sister), and both my grandmas use おばあちゃん as first-person pronouns when they talk to me.

For example, when I hang out at my grandma's place, she might say:

- おばあちゃんがお茶入れてやろうか?

- Can I get you a cup of tea?

Or my sister might say something like:

- お姉ちゃんのアイス勝手に食べたでしょ!

- You ate my ice cream without permission, didn't you?!

You might be wondering if I then refer to myself as 孫 (grandchild) or 妹 (younger sister) when responding to them. No, because I'm the youngest, or of the lowest status (formally speaking) in my family.

My mother uses お母さん (Mom), my father uses お父さん (Dad), my older sister uses お姉ちゃん (older sister), and both my grandmas use おばあちゃん as first-person pronouns when they talk to me.

In Japan, this family-role-as-first-person-pronoun example generally applies to those who are older or have higher status than the person they're talking to. A good rule of thumb is that if your family role can take the name enders さん or ちゃん (お父さん, お母さん, etc.), you can use it as your pronoun.

The cultural background behind this practice is the Japanese mindset around the importance of family structure and respect for the elderly. As a parent, you want your kids to differentiate you from other adults to remind them of your higher status in the family, so that they recognize you as someone to respect. In most cases, however, it's more of a subconscious custom and doesn't necessarily point to whether a family is strict or not. In fact, this practice makes me feel closer to my family and gives me more affection for them. ❤️

Every family is different. Some grandparents might call themselves ばあば/じいじ, while parents might call themselves ママ/パパ — they might even choose to use 私/僕, as they do outside the home. Some may use family roles and then switch to the usual pronouns as the kids grow up.

While you'll usually only refer to yourself by your role in the family when you talk to someone younger, here's an exception: It's common for married couples to call each other お父さん (Dad) and お母さん (Mom) as if speaking from their kids' perspectives, even when their children aren't present. Now I think about it, it is kind of weird to call your husband "dad" in English, but it's not strange at all in Japanese!

Keep in mind that there are times when people might use family role pronouns outside the family too. When talking to a young child, for example, you might call yourself おばちゃん, おじちゃん, お姉ちゃん, or お兄ちゃん. Say you come across a kid on the street trying to get their balloon unstuck from a tree branch. If you're a young woman (or at least see yourself as a young woman, like I do), you might say:

- お姉ちゃんが手伝ってあげようか?

- May I help you?

Similarly, when my friend's dad talks to me, he could say:

- おじさんは、来年退職するんだ。

- I will retire next year.

Finally, if you're a professional in a certain industry (especially childcare or education), you can sometimes use your profession as your pronoun. A common case is when teachers call themselves "teacher."

- 注目!先生の話きちんと聞いて!

- Attention! Listen to me carefully!

This is similar to the use of 僕 for little boys — applying a child's perspective to your interaction with them.

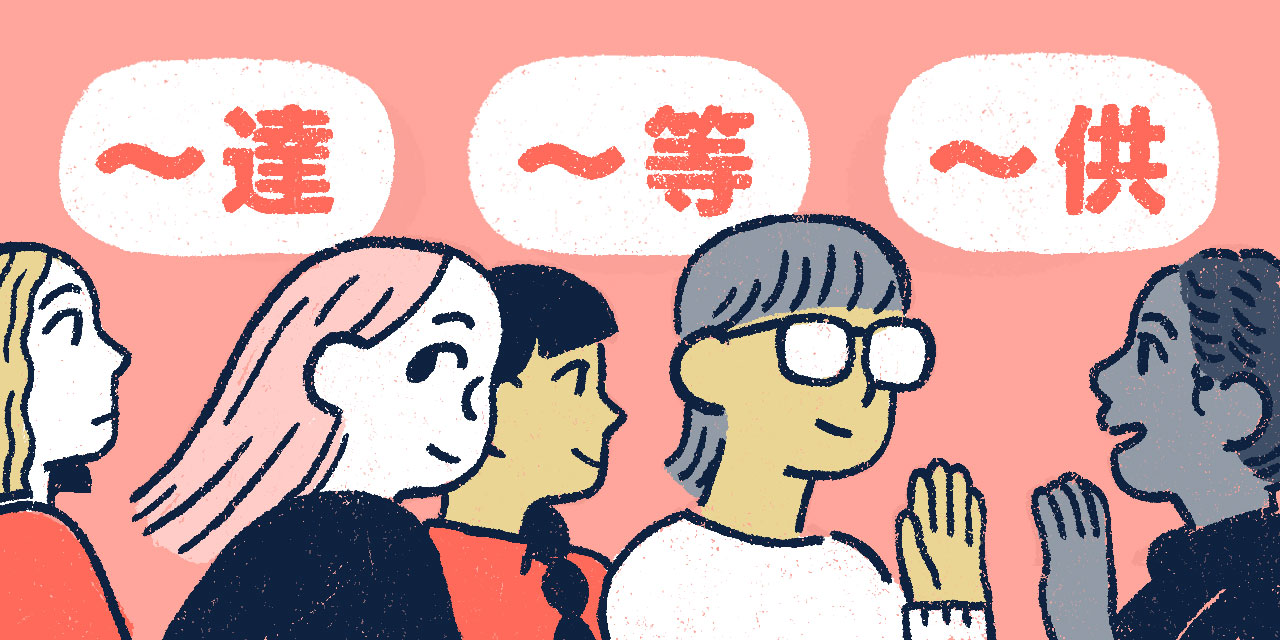

Pluralizing Suffixes

Sometimes you want to talk about more than just yourself. You want to rope other people into the action! This is when you attach a pluralizing suffix to the end of your choice of first-person pronoun — you turn your "I" into "we."

〜達

The pluralizing suffix 達 (たち) works like this: 私 (I) + 達 = 私達 (we).

Historically, 〜達 was used to pay respect to the person you were talking to — so it wasn't appropriate to use 私達 in formal situations. Today, 私達, 僕達 and 自分達 are all pretty neutral in terms of the formality.

- 私達はワニカニという漢字学習ウェブサイトを運営しています。

- We run a kanji-learning website called WaniKani.

If you want to present yourself (and your company) more politely, 私供 is more appropriate.

The majority of common first-person pronouns pair with 達 just fine, but keep in mind that one doesn't work: うち達. It sounds awkward, and is difficult to say.

〜等

Another pluralizing suffix is 等 (ら), the kanji of which can also be read as など, meaning "etc." 等 is used more commonly by males and people living in Kansai.

Even though dictionaries claim that 〜等 shows more humility than 〜達, in reality, its feeling can change depending on the situation, and the pronoun it's paired with.

- 僕らに、掃除させてもらえませんか?

- Could you let us clean?

- 何で俺らが掃除しなくちゃいけないんだよ。

- Why do we have to clean?

〜供

Earlier, I mentioned 私供 (わたしども, わたくしども). This is the best way to use the pluralizing suffix 供. It can fit with other first-person pronoun combinations, but 私供 is by far the most common, as the formality of 私 and the humbleness of 供 go well together.

In a conservative, formal situation, 〜供 is a much better choice than 達 or ら for pluralizing your pronoun.

- 私供にお任せください。

- Leave it to us.

Uncommon Pronouns (Used in Real-Life)

The following pronouns aren't used as often as the ones we just covered, but Japanese people still use and recognize them. They pop up in books, movies, and other media. If you want to add humor or personality to your conversation, they're fun to sprinkle in every once in a while.

わし/わい

In fictional stories, わし is the way wizened old hermits and elder sages refer to themselves — in other words, it's a stereotypical pronoun for old people, especially old men. It's also common in some dialects, mainly used by male speakers no matter the age of the speaker.

- わしも、もうそんなに長くないんじゃ。

- I won't be living for much longer.

These days, interesting trends have emerged around わし and its version with the "sh" sound dropped, わい. Both are gaining popularity nationally, regardless of gender. It's been used as internet slang for a while (often typed in katakana, as in ワシ or ワイ), and as of 2020 it's also gaining popularity among high school girls.

私め

If you want to be very modest and respectful towards someone, you could use 私め (わたしめ, わたくしめ). The suffix め is used to convey disdain or anger towards people (and sometimes animals). So if you use it on yourself, it conveys humility. You might not find much use for it these days, except when you're being sarcastic or a total kiss-ass.

- あなた様にそう言って頂けるなんて、私めは光栄でございます!

- I'm terribly honored that Your Majesty said that to me!

あたい

Remember how あたし is derived from わたし by dropping the "w" sound? Well, あたい is derived from あたし. Originally used by geisha, あたい is quite feminine. But in the Shōwa period, rebellious girls who hung out with biker gangs started using あたい, and the pronoun took on a bad-girl vibe. It's not common anymore, but あたい is a fun way to give your speech an aggressive tone and jokingly fight with someone.

- 今、あたいに何て言った!?

- What the heck did you just say!?

おら/おいら

Just like おれ, both おら and おいら are mainly used by men.

Just like おれ, both おら and おいら are mainly used by men. Both pronouns are strongly tied to dialects from the Tohoku region. Though used less by younger generations, my Tohoku grandparents still use おら and おいら on a regular basis. These pronouns can sound pretty nerdy these days, because they're mostly associated with young boy anime characters like Shin-chan or Goku from Dragon Ball.

- オッス!おら、悟空。

- Hi! I'm Goku.

おら and おいら have a vibrant "boyhood" feel to them. Some people use them in casual conversation to mimic the likability of cartoon characters. But they still sound like… cartoon characters, so it can be a little awkward.

吾輩/我輩

You may have read the pronoun 吾輩 (わがはい) in the title of Soseki Natsume's famous novel 吾輩は猫である (I Am a Cat). The cat in the novel refers to himself as 吾輩. 吾輩 (also written as 我輩) is considered old-timey, egotistical, and mostly used by men. Not many people choose it these days aside from the rock singer デーモン閣下 (His Excellency Demon), who uses it to maintain his dignified place among his loyal followers.

- 吾輩は、人間界で布教活動をする悪魔だ。

- I am a demon who is engaged in missionary work in human society.

俺様

If you've read our article about Japanese name enders, you can probably guess that 俺 (おれ) + 様 (さま) is a rude and arrogant combination. You don't usually use 様 with yourself, so adding it to an aggressive pronoun like 俺 is a way to intentionally elevate yourself — and disrespect others in the process.

- 俺様の言うことを聞け!

- Listen to what I say!

Pretty rough, right? Even so, this phrase is used a lot by sassy, controlling boy characters in manga aimed at girls.

You can also use 俺様 as an adjective to describe disrespectful, arrogant people.

- あいつって、俺様彼氏だよね。

- He is such a dominating boyfriend.

僕ちゃん/僕ちん

Another possible pairing between a first-person pronoun and a name ender is 僕ちゃん (ぼくちゃん). 〜ちゃん is used for girls and little boys, and 〜ちん is the nickname-y version. Both 僕ちゃん and 僕ちん sound like baby talk, and I've never heard an adult use this pronoun to refer to themselves, unless they were joking. In fact, the last time I heard anyone use it seriously was in preschool.

- 僕ちゃんね、絵描くのが得意なの。

- I am good at drawing pictures.

Just like 僕, 僕ちゃん and 僕ちん are also used as second-person pronouns for little boys, so some people may say it to others to make fun of them for being immature.

俺っち

〜っち has become a popular ender for nicknames recently because it adds affection and friendliness and sounds catchy (like "tamagocchi"). You'll often hear 俺っち — a casual, laid-back form of おれ — because Jibanyan from Yokai Watch says it.

- 俺っち、最近ゲーセンよく行くんだよね。

- I often go to the arcade these days.

In Shizuoka Prefecture, 俺っち is used as 俺達, the plural form of 俺.

余

Kings, high-ranking samurai, and intellectuals used to use 余 (よ) as a first-person pronoun. Today, you may still encounter it in very formal writing or political campaigns, as well as Chinese classics and historical dramas.

- 余は満足じゃ。

- I'm satisfied.

拙者

If you've ever wanted to speak like a samurai, the pronoun 拙者 (せっしゃ) can make your wish come true. The first kanji in the word comes from 拙い, which means "clumsy," and is used to add modesty. But the pronoun has evolved over time, and it can be used with an arrogant attitude when talking to someone of lower status. You're a samurai, after all.

- 拙者は、コウイチでござる。

- I am Koichi.

(Samurai pro tip: use the sentence-ending particle 〜でござる to sound even more samurai-like!)

わらわ

Originating from an archaic word for child (童, わらべ), わらわ is a defunct, formal first-person pronoun women use to sound modest. While there's nothing inherently feminine or high-class in the word, it's used today in fictional stories by female characters who are usually princesses, goddesses, or from a high-ranking samurai family.

- わらわにくださるのですか?

- Would you give that to me?

WATASHI Am Glad You Made It This Far!

We made a Japanese first-person pronouns cheatsheet you can use to study everything you just learned.

Now that you know all the important and useful Japanese first-person pronouns, you'll have an easier time deciding which one fits your personality and the vibe of the situation (as well as how to use the pronoun you choose). It will take practice to use them effortlessly, but with time and study, you'll get there.

As you've seen, Japanese first-person pronouns are closely linked to gender identity. There are tendencies for certain pronouns to be used more by certain genders, and many have feminine or masculine connotations accumulated through their use. However, the line between them is becoming more blurred. Remember, it's all about how you want to express yourself in a given situation, and hopefully this article will help you to find one (or more) that fits your vibe.

But wait! We're not quite done yet.

We made a Japanese first-person pronouns cheatsheet you can use to study everything you just learned. Reading this article put all the information in your head, but it won't stay there long without some kind of quick-reference material you can study regularly. Oh wait! Here's one right here.

Just sign up for our free Tofugu newsletter (also useful), and you'll get access to this study sheet and all past and future Tofugu freebies too.

-

Known as 音便 in Japanese, "euphonic changes" are variations in pronunciation that take place over time. ↩