Table of Contents

The Basics

The particle が goes after a noun to show us that the noun is the subject of a sentence. That is, the noun before が is the person or thing that's doing whatever comes next. In other words, が marks the grammatical subject. Beyond marking the subject, が also puts emphasis onto that subject, and excludes other possible subjects.

Patterns of Use

The particle が always goes immediately after a noun — or something that behaves like a noun — to show that this noun is the subject. For example, in the sentence below, あの犬 (dog) is the subject. It is the one doing what comes next. In this case, that's the verb "barked":

- あの犬が吠えた。

- That dog barked.

In this next sentence, the subject is 誰か (someone), and that someone is doing what comes next, in this case "existing":

- 誰かがいる。

- Someone's here.

(Literally: Someone exists.)

In this final example, the subject is この納豆 (this natto). What is "this natto" doing? It's being delicious 🤤

- この納豆がおいしい。

- This natto is delicious.

Conceptualizing が

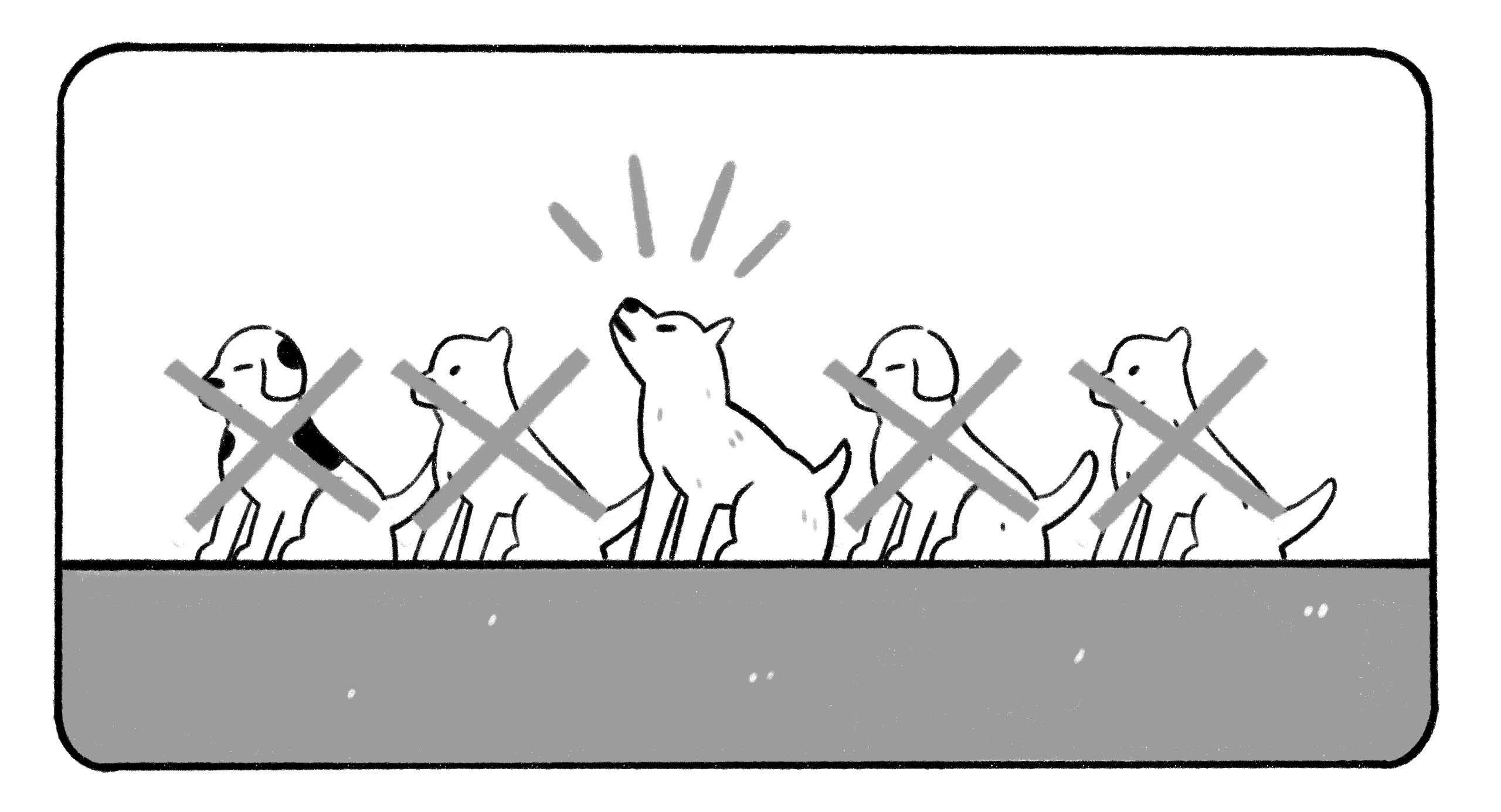

So just to recap, the particle が points a finger at the subject in the sentence, and in doing so puts emphasis on that subject, telling us that it is a very important piece of information in the sentence. We like to think of が as the witness in a police lineup. It is picking out the subject from a lineup of potential subjects, and saying, "this is the one that did it."

As with a lineup, the act of picking out the subject — the doer — also lets the others in the lineup off the hook. So, が is simultaneously telling us what the subject is, putting emphasis on it, and making it clear that nothing else is the subject.

To give you a better idea of what we mean, let's look at an example. Imagine everyone at Tofugu is hanging out, and someone from outside the company is trying to figure out which one of us is the president. They might say:

- どの方がトーフグの社長さんですか?

- Which person is the president of Tofugu?

Koichi raises his hand shyly and says:

- 私が社長です。

- I'm the president.

Both the question and the answer use が, because が emphasizes that Koichi is the president, and excludes everyone else from that position.

By way of comparison, if someone asked Koichi what his role was, he might answer 私は社長です. To read more about the differences in nuance created by は and が, take a look at our article.

Subject Omission

Subject omission is extremely common in Japanese when we know what that subject is from context. Take a look at the dialogue below, for example:

- うちの犬が何かしましたか。

- Did our dog do something to you?

- 吠えました。

- It barked.

In English, we use "it" to refer to the dog. We can't just say "barked." In Japanese, however, we can simply use the verb, and leave the subject out altogether. In this context, every Japanese speaker knows we're talking about the dog, so there's no need to mention a subject at all.

Because it's so common to leave out the subject, leaving it in can often bring a certain nuance to the sentence. This isn't actually all that different from English. For example, imagine we responded to the question above with:

- おたくの犬が吠えました。

- Your dog barked.

In English, referring to the subject as "your dog" rather than "it" throws a certain emphasis onto the dog, right? The same is true of the Japanese version. Choosing to include the subject when it's more natural to leave it out leads to the subject being emphasized. Maybe you're doing that to show how annoyed you are about the dog barking at you, or maybe the dog is freaking you out.

が Omission

Even when the subject is included, it is really common to omit が in informal speaking, as well as writing that closely resembles spoken styles, like casual text messages. This generally doesn't result in any significant difference in nuance.

- 犬(が)吠えた。

- The dog barked.

- 誰か(が)いる。

- Someone's here.

It's also possible to omit が in polite speaking. Again, in this case there is little or no difference in the nuance. It simply comes down to the individual preference.

- お車(が)到着致しました。

- The car has arrived.

However, there are some circumstances in which you can't omit が. Remember how we said that が is used to pick the subject out of a crowd? Well, when that's its main role in the sentence, が has to stay put.

- ジェニーが犯人だ。

- Jenny's the culprit.

Here, we really are pointing our fingers at the perpetrator, and ruling out other suspects. が would therefore always be kept in sentences like these.

が with "Objects"

Many textbooks and linguists say that が can also mark the object, but others believe it's still marking the subject in these situations. We believe that it's more helpful and consistent to consider that が always marks the subject in Japanese, even when the same word is the object in the English translation.

が with Verb-like adjectives

The first obvious example of this is the use of が with things we like, love, hate, want, and so on. In English, the objects of our desire or distaste are exactly that — objects. In Japanese, however, they can be considered subjects, because they are the ones that are desirable, or detestable.

- 梅干が大好き。

- I love umeboshi.

(Literally: Umeboshi is loveable)

- 小犬が欲しい。

- I want a puppy.

(Literally: A puppy is desired)

- そういうのが嫌いだよ。

- I hate that sort of thing.

(Literally: That sort of thing is detestable)

In English, the subject of these sentences is clearly "I." In Japanese, though, we can argue that 梅干 (umeboshi), 子犬 (puppy), and そういうの (that sort of thing) are the subjects of the adjectives that follow them. The person doing the loving, wanting, or hating — who doesn't need to be specified in Japanese when it's obvious, and especially when they're the speaker — is considered to be either the invisible topic, or another invisible subject, depending on whom you ask. And 大好き (loveable), 欲しい (desired), and 嫌い (detestable) are all adjectives that describe their respective subjects.

To move onto another example, "want" is a verb that generally takes an object in English. You want something. That thing is the object, and you're the subject.

Not in Japanese. To say that you want to do something in Japanese, you can change the verb into the たい form, as in 食べたい (I want to eat).

- 梅干が食べたい。

- I want to eat umeboshi.

See that い on the end? That's a clue that this form has basically "become" an い-adjective, so it can now act like other い-adjectives in lots of ways. To follow our logic from earlier a little further, we can think of this as literally meaning, "Umeboshi is desirable to eat for me." This might feel like even more of a stretch than the others, but it can be helpful in understanding the difference in structure between English and Japanese!

We should point out that it's also totally possible to say 梅干を食べたい, but this changes the nuance somewhat. The most likely interpretation if you use を is that you're not only craving pickled plums, but you are more practically thinking about eating some. The particle を shows that you have more intention of following up on what you want. The sentence with が, on the other hand, implies that you have a spontaneous desire to eat pickled plums, which may or may not be fulfilled.

が with Verbs that Describe States

Have a look at the sentence below, along with its most obvious translation into English:

- 日本語が分かる。

- I understand Japanese.

Although this is the most natural way to translate it into English, it doesn't show us what's really going on in the Japanese sentence. It would probably be more helpful (but of course less natural) to translate it as:

- 日本語が分かる。

- Japanese is comprehensible (to me).

The same is true of verbs like できる:

- それができる。

- I can do that.

Again, a more helpful translation might be:

- それができる。

- That is doable (for me).

And 見える and 聞こえる:

- その人が見える。

- I can see that person.

(Literally: That person is visible (to me).)

- 音楽が聞こえる。

- I can hear music.

(Literally: Music is audible (to me).)

This actually boils down to the difference in where we draw the line of what is a subject in English, compared with what it is in Japanese. In English, "understand" and "can see" are used in a transitive way, which means that the things that are understood and seen are the grammatical objects of the sentence. However, the Japanese equivalents 分かる and 見える are intransitive, which means that the subject does something all by itself, rather than having something done to it.

You can read more about the different takes on transitivity in English and Japanese here.

が with Verbs for "Exist"

We're already seen an example of the verb いる used in it's basic meaning "to exist." You can also use the verbs ある and いる (both "exist") to talk about things that you have. In this case, が is still used to show us what exists.

- 私(に)は夢がある。

- I have a dream.

(Literally: A dream exists for me.)

In English, the dream is the object of the verb, because we consider that we are doing the having to the dream. In Japanese, on the other hand, the dream is the one that's doing the action — it's existing.

The exact same logic is behind these next two sentences:

- かなえ(に)は可愛い犬がいる。

- Kanae has a cute dog.

(Literally: A cute dog exists for Kanae.)

- まみ(に)は素敵な子供が二人いる。

- Mami has two lovely kids.

(Literally: Two lovely kids exist for Mami.)

In English, the Kanae and Mami are doing the having. In Japanese, the dog and kids are doing the existing.

Beyond The Basics

が in Relative Clauses

The particle が is generally used in relative clauses — clauses that give extra info, not vital to the sentence — even if は is used in the corresponding main clause.

Let's take a look at an example of a main clause first:

- スミスさんはお金を見つけた。

- Mr Smith found some money.

This is a complete sentence in its own right (a main clause). In this example, it's most likely that スミスさん is considered the topic and marked with the topic marker は. If we did choose to marks スミスさん with が, it would often be to pick him out specifically, and emphasize that others didn't find the money.

However, if the sentence is a little more complicated and includes a relative clause, it's more common to use が than は:

- [スミスさんが見つけた]お金だ。

- That's the money [that Mr Smith found].

In relative clauses like these, が can generally be replaced with の, as in this example:

- [スミスさんの見つけた]お金だ。

- That's the money [that Mr Smith found].

Let's take a look at another example of when の can replace が:

- スイスは物価が高い。

- Switzerland has a high cost of living.

(Literally: As for Switzerland, the prices are high.)

This is also a complete sentence. Here, we cannot replace が with の.

If we want to use it as a relative clause, and describe something with it, we can put it in front of the noun that we want to describe. In the following example, the noun we want to describe is 国 (country):

- スイスは[物価が高い]国だ。

- Switzerland is a country [where the cost of living is high].

(Literally: As for Switzerland, it's a country that has high prices.)

Now we can replace this が with の:

- スイスは[物価の高い国]だ。

- Switzerland is a country [where the cost of living is high]. (Literally: As for Switzerland, it's a country that has high prices.)

Whether you choose が or の is mostly a question of style, as の can make the sentence flow more easily.

The reason that が and の are sometimes interchangeable in this way is rooted in the past, the remnants of which can still be seen in the way が appears in set expressions like 我が国 (our country), 我が子 (our child), 我が家 (our home) and so on.

が in Embedded Clauses

が is also generally used in embedded clauses even if は is used in the corresponding main clause. Let's go back to our noisy dog to see what we mean:

- 犬は吠えました。

- The dog barked.

But if someone tells you that the dog barked, what that person said becomes an "embedded clause" and, just like with relative clauses, particle が is the more typical choice:

- 犬が吠えたと言いました。

- They said that the dog had barked.

Just in case you were wondering, the particle の can't replace が in this case!

Two Subjects with が

It's possible to have two subjects, each marked by が, in a Japanese sentence. However, when this is the main clause, one of the subjects will usually be presented as the topic, as we saw earlier in this example:

- スイスは物価が高い。

- Switzerland has a high cost of living.

If we choose to keep both が in a main clause, its nuance of excluding other subjects and emphasizing this one subject is heightened:

- スイスが物価が高い。

- It's Switzerland that has a high cost of living.

If it's an embedded clause, though, が loses that emphasis:

- 先生はスイスが物価が高いと言いました。

- The teacher said that Switzerland has a high cost of living.