Ah, Tokyo, that shining island paradise. Turquoise waters. Palm trees and coconuts. Grass skirts and piñ a coladas.

What’s that you say? These images don’t leap to mind when I say “Tokyo”?

Well, to be fair, grass skirts haven’t really caught on across most of the city (alas). But the administrative area known as the Tokyo Metropolis actually includes several collections of islands, many of which lie hundreds of miles from the Japanese mainland.

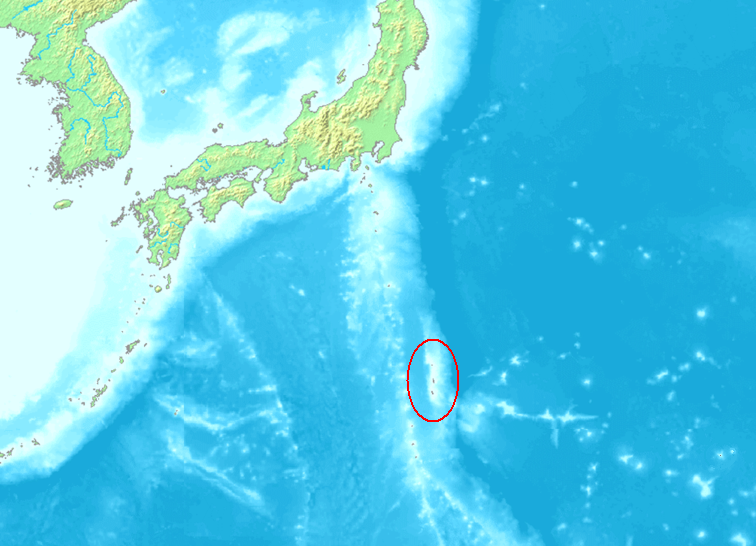

Why am I telling you this? Because I happen to be one of those lucky island groups, basking in the subtropical Pacific sun. I have several names, but people usually call me the Ogasawara Islands or Bonin Islands. Nice to meet you! Let me tell you about myself.

My Specs

I consist of about 30 small islands, lying some 500 miles south of the mainland. I have a voluptuous figure, hilly and heavily forested. My temperature averages a balmy 23°C (73°F), with a typical range of about 18-28°C (64-82°F) throughout the year.

I have a fiery disposition. That’s because I’m made up of volcanic islands (aka oceanic islands), composed of lava eruptions from the sea floor. Just last year, in fact, I added a new island to my collection: Niijima. Don’t touch, it’s still piping hot!

I have many pets, including various birds, bats, and reptiles. I also provide a home for over 2000 humans. They live mainly on my two largest islands: Chichiijima (“Father Island”), the biggest, and Hahajima (“Mother Island”).

But hey, a picture’s worth a thousand words so…what’s a 360 degree panorama worth?

My Animal Friends

Remote islands like me tend to host endemic species; that is, species that are unique to a given area, because they evolved in isolation and couldn’t spread elsewhere. I have an exceptional proportion of endemic species, including 40% of my plants, 80% of my birds, and 90% of my land snails. (Bet you’re jealous of whoever had the job of cataloguing my species of land snails.)

I’m so blessed with endemic species that I’m known as the “Galapagos of the Orient”. My most famous endemic species may be the cuddly Bonin flying fox (aka Bonin fruit bat)…

…and the adorable Bonin petrel.

Unfortunately, many of my creatures are under threat, thanks to my humans (the most troublesome pet of all). You know how humans can be, cutting down forests and introducing invasive species. The introduction of rats, for instance, decimated many of my birds. (Seriously, humans? You couldn’t leave the rats behind?)

And yet, for all the trouble they cause, humans are worth having around. They’re incredibly resourceful, adventurous, and expressive. They aren’t nearly as cute as bats or petrels, but you get used to them.

My First Humans

Way, way back in the stone age, I adopted my first set of humans. These early seafarers crafted sophisticated stone tools and canoes, as well as many works of pottery.

Culturally speaking, my stone age people combined elements from the Japanese mainland with Polynesian features, as illustrated by the designs of their ceramics and fishing gear. So even way back then, I was quite the cultural melting pot! They were great sailors and fishers, zipping around my islands in large outrigger canoes, which could be rowed or sailed.

Sometime during the first millennium AD, however, my humans disappeared. I really don’t know why. I anguished over it for a long time, wondering if I had offended them somehow. Maybe I was devoting too much attention to my land snails?

Then, just when I had nearly forgotten all about humans, they came back.

Return of the Humans

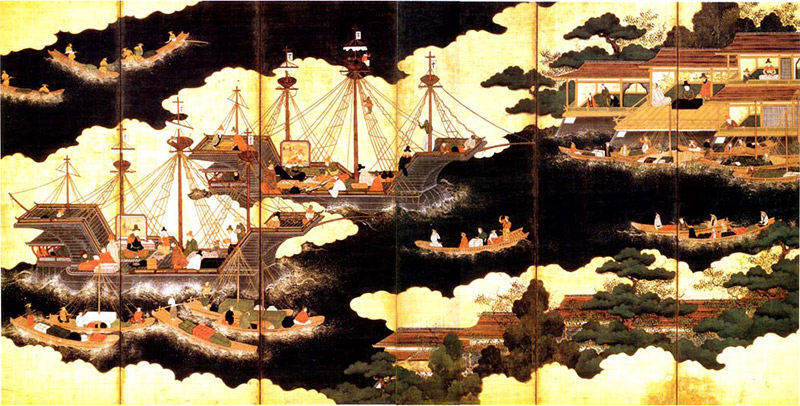

One of Japan’s best-known features is its high degree of ethnic homogeneity (though not so high as is often thought). Due to the pioneering spirit of diverse peoples, I am a glaring exception to this rule.

I’m not sure which humans first spotted me in modern times. It was likely the Japanese, though it might have been early Spanish explorers. At any rate, I was officially claimed (humans have such nerve!) by the Japanese in the sixteenth century. Japan was really caught up in this whole “isolationism” thing, though, and never even called me afterwards, let alone visited me.

The traditional account holds that my human discoverer was the samurai Ogasawara Sadayori, hence my Japanese name. Incidentally, my other most-used name, “Bonin”, apparently derives from the Japanese word for “no people”. As you will see, this latter name is totally outdated.

Not until the nineteenth century did any humans actually come to live on me again. My first modern settlers were a motley crew, hailing from various Western, African, and Polynesian countries, and speaking about 20 languages in all. Due to a high proportion of English-speaking immigrants, a common tongue emerged in the form of pidgin English, rooted in multiple English dialects (including British, American, and Hawaiian) and influenced by various European and Austronesian languages.

The Japanese were quite surprised when they noticed that settlers had arrived on my shores, dubbing them the “westerner islanders”. Then, as modern Japan emerged from the ashes of feudalism in the 1870s, they finally got around to reclaiming me (after making me wait all those centuries!). To be fair, they didn’t mess around this time. Thousands of Japanese settlers arrived, and international support was successfully garnered for their territorial claim, thwarting those of Britain and the United States.

By the mid-twentieth century, I was happily nurturing some 7000 humans, spread over a dozen of my islands. Given the sheer number of arrivals from Japan, the lingua franca was heavily influenced by the Japanese language. Cultures mashed together in wonderful ways, and the benefits of modernization trickled in. Times were good.

But they didn’t last. Soon, I faced the most unpleasant experience of all my thousands of years.

War, What is it Good For?

Sometimes humans don’t get along so well. I witnessed this first-hand in World War II, given that I was a key strategic position for control of the Pacific. First there was an immense military buildup upon my islands, followed by many battles, Iwo Jima being the best known. My cliffs still bear the scars of exploding shells, and my waters house the skeletons of sunken war vessels. Most of my population was evacuated to mainland Japan.

After the war, island residents were allowed to return…but only those of American or European descent. (For those who lack experience with humans: no, I am not kidding. They really do discriminate horribly against one another based on slight genetic differences.) Only with the end of American occupation in the 1960s were my ethnically Japanese humans able to return.

The Sun Will Come Up

Fortunately, those grim days are behind me. Things are much better now.

Unlike most remote islands, my population has actually swelled by some 500 people so far this century. This is partly due to immigration by people looking to become fishermen, as well as retired Japanese folks searching for an island paradise to spend their golden years.

A ferry, the Ogasawara Maru, runs constantly between me and mainland Japan, completing a trip every few days. In addition to tourists, the ferry drops off supplies from the mainland and picks up loads of fish and shellfish. For my humans, the Ogasawara Maru is the main link to the outside world. They sometimes talk about building an airport, though I’m not sure the idea will ever get enough support.

Naturally, tourism flourishes in all pursuits sea-related. Diving, snorkeling, whale watching, fishing, surfing, and kayaking are all popular activities around my islands.

Tourists also love my unique cultural experience. Just as in stone age times, my islands boast a complex melding of many traditions, Japanese and Polynesian prominent among them. One famous example is Nanyou Odori (“South Pacific Dance”), in which Hawaiian dancing meets Japanese instruments, such as taiko drums!

Goodbye! Sayōnara! Aloha!

Well, I hope you found me interesting, perhaps even interesting enough to come for a visit. While humans can be difficult to manage, I have a good feeling about you…I’m confident you won’t make any trouble. If you do come out to see me, though, please don’t bring any critters along…we don’t want a repeat of the rat escapade.