I remember reading Japanese poetry for the first time in the second grade. Don't ask why it stuck with me; I just remember reading a haiku by Matsuo Bashō and thinking it was awesome. I remembered it well enough that I sought out Bashō's poetry as I grew older. Along with video games, I attribute Bashō with fomenting an early interest in Japan for me.

Here's the lesson: if a seven-year-old can read and enjoy Japanese poetry, so can you. I consider the appreciation of Japanese poetry to be like an onion: there are many, many layers to it. The outmost layer is simply reading Japanese poetry in translation and enjoying it as it is. At its deepest core, enjoyment is reading it in the original Japanese, with deep knowledge of the range and breadth of both Japanese and Chinese poetry (Japanese poetry is full of references to Chinese poetry and other Japanese poetry).

My goal here is to give you a very broad overview of the history of Japanese poetry and a crash course in its terminology. I'll leave plenty of space for the poetry itself, which I believe is the best way to show you how great it is. In fact, if you're not interested in learning what the types of poetry are called ("Terminology" below) and when they were written ("History" below), just skip on down to the poetry section. Enjoy!

Terminology

Traditional Japanese poetry comes in many highly technical forms. You've probably all heard of haiku, but there are many more types of Japanese poetry. The most significant are the chōka, tanka, renga, haikai, renku, hokku, and haiku.

The chōka and tanka are both forms of waka. In a nutshell, the chōka is a long waka, and the tanka is a short waka. Over time, the tanka became much more popular; as a result, waka and tanka are sometimes used interchangably.

According to the amazing Princeton Companion to Japanese Literature: the renga is made up of linked stanzas of tanka, "joined in sequence so that each made an integral poetic unit with its predecessor . . . but without semantic connection with any other stanza in the sequence made of such alterations." It probably won't surprise you to learn that there were crazy complex rules as to what kinds of stanzas went in what order, and a single renga might be written by as many as three different poets.

The haikai is a relaxed form of renga (originally with light-hearted themes as well), and renku is the modern name for haikai. The hokku is the opening stanza of a renga or haikai with three lines of 5-7-5 syllables. If you're familiar with haiku, that structure will sound mighty familiar. In fact, the haiku developed out of the hokku – but the concept of the haiku as a freestanding form wasn't developed until the late 1800s. Yes, this means that Bashō, who is generally thought of as the greatest haiku poet, didn't technically write any haiku, since they didn't exist when he was around. Bashō wrote a lot of hokku though!

There's a lot more depth, meaning, and technical differences between all of these terms – and plenty of terms that I left out. But having some idea about these is a good place to start.

History

There seems to be little consensus among scholars as to how Japanese poetry should be historically divided and classified, except that there is old poetry and modern poetry. So, even if I wanted to give you a detailed, blow-by-blow diatribe on the eras of Japanese poetry, I'd be hard-pressed to do so without parsing a lot of sources. Instead, I've touched here on some of the more important works and players and tried to provide some broad context in the process.

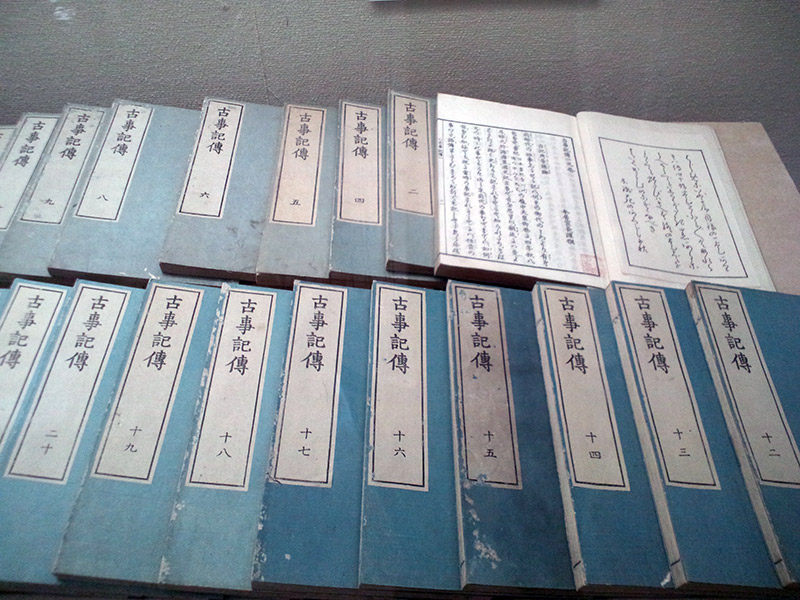

The earliest Japanese poetry was part of an oral tradition and is almost entirely lost. And even once the Japanese started writing stuff down, a lot of the early emphasis was on poetry in Chinese ("kanshi"). The first major written collection of Japanese poetry (in Japanese) is found in the Kojiki, dated 712 C.E. The bulk of the Kojiki is devoted to stories about the gods and Japanese rulers. Eight years later, the Nihon Shoki was produced; it too focused on gods and rulers. These early compositions also recorded some poems and songs that had been passed down orally.

And then, less than fifty years later, came the Man'yōshū, the book of "Ten Thousand Leaves", whose last datable poem was penned around 759. It is the oldest extant collection of Japanese poetry. The Man'yōshū is huge (20 volumes) and its poems span almost two centuries (sometime around 600 C.E. to 759 C.E.). Unlike later collections, the Man'yōshū wasn't organized very rigidly and, although we think of it as a Japanese collection, it contained some Chinese-language poetry and prose as well. Many of its poems were anonymous, ostensibly written by frontier guards and other normal folk. But the poems that were written by non-scholars were generally rewritten by the formal scholars and poets whose work makes up much of the Man'yōshū. The Man'yōshū was hugely influential on subsequent generations of Japanese writers and poets, and it remains one of the most important works of Japanese literature.

In the early 10th century, the Kokinshū, a collection of waka, was commissioned and completed. Like the Man'yōshū, the Kokinshū included poems spanning several centuries. Unlike the Man'yōshū, the Kokinshū was rigidly organized by topic, a theme that would have a huge impact on subsequent poetry in Japan. Organization was taken seriously at all levels; for example, the love poems were ordered in such a way "to show the presumed process of a courtly love affair." (Princeton Companion)

Around the same time as the Kokinshū, a number of female writers rose to prominence in Japan. Fujiwara Michitsuna's mother ("The Gossamer Years"), Murasaki Shikibu ("The Tale of Genji"), Sei Shōnagon ("The Pillow Book"), Izumi Shikibu, and Sugawara Takasue no Musume ("The Sarashina Diary") were among the many prominent female writers of the time. Although these women primarily wrote prose, poetry was an integral part of most of their works. Poetry compilations of the time include many of their poems.

A bit later, in the 12th century, the Buddhist monk Saigyō wrote waka that would have an enormous impact on Bashō and other subsequent Japanese writers. In the early 13th century, the Shinkokinshū was compiled and published. Like the Kokinshū, it has twenty books and almost two thousand poems. Its poems span hundreds of years, some dating back to the time of the Man'yōshū. The renga, which had existed for hundreds of years, evolved into its own distinct style around this time.

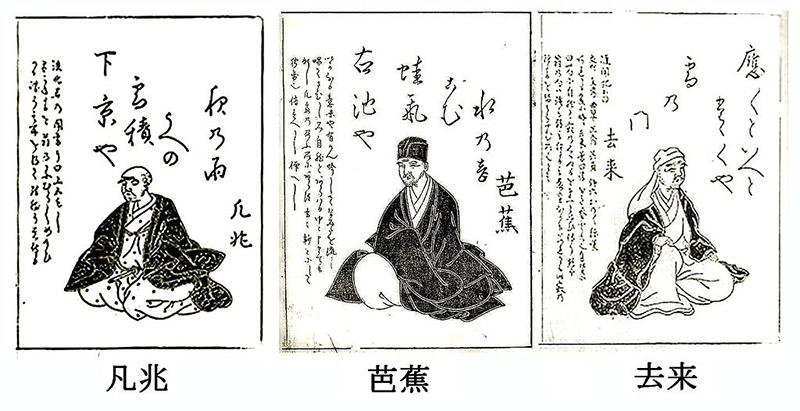

The next major event in Japanese poetry came in the 17th century, when the haikai became extremely popular, in large part due to the work of Matsuo Bashō. Bashō was a prolific writer and traveler who wrote hokku, haibun (a style that combines prose and poetry), and other forms of poetry and prose. I believe the Princeton Companion's entry on Bashō says it better than I can:

In an age of political rigidity and control, [Bashō's] sense of time, suffering, and death led him to combine – with a skill no other lyric poet has shown – the high and the low, the objective with the subjective, the commonplace with the tragic. . . . Much of our knowledge of our world and ourselves may be derived from his writing.

After Japan opened to the West in the 19th century, Japanese poetry underwent a transformation as a result of the influence of Western poetry. More freeform styles of poetry began appearing, and the more traditional styles underwent their own transformations. Many Japanese poets who wrote after World War II are labeled as "post-war", although newer poetry is frequently labeled as simply "modern."

The Good Stuff

And now for the actual poetry! The original Japanese is provided when possible and poems are ordered chronologically by birth date of author.

On the Death of the Emperor Temmu by Empress Jitō (645-702), from Women Poets of Japan

Even flaming fire

can be snatched up, smothered

and carried in a bag.

Why then can't I

meet my dead lord again?

Untitled by Kakinomoto Hitomaro (d. 708-715), from One Hundred Poems from the Japanese

Kamo yama no

My girl is waiting for meIwane shi makeru

And does not knowWare wo kamo

That my body will stay hereShira ni to imo ga Machitsutsu aramu

On the rocks of Mount Kamo.

Man'yōshū, XIX: 4290 by Ōtomo Yakamochi (718-785), from Japanese Court Poetry

Haru no no ni

Now it is spring –Kasumi tanabiki

And across the moors the hazeUraganashi

Stretches heavily –Kono yūkage ni

And within these rays at sunset,Uguisu naku mo.

A warbler fills the radiant mist with song.

Man'yōshū, XIV: 3570 by Anonymous, from Japanese Court Poetry

Ashi no ha ni

I shall miss you mostYūgiri tachite

When twilight brings the rising mistsKamo ga ne no

To hang upon the reedsSamuki yūbe shi

And as the evening darkens coldNa oba shinuban.

With mallards' cries across the marsh.

Kokinshū, XVII: 879 by Ariwara Narihira (818-893), from Japanese Court Poetry

Ōkata wa

Lovely as it is,Tsuki o mo medeji

The moon will never win my praise –Kore zo kono

No, not such a thing,Tsumoreba hito no

Whose accumulated splendors heapOi to naru mono.

The burden of old age on man.

Untitled by Ono no Komachi (833-857), from Women Poets of Japan

He does not come.

Tonight in the dark of the moon

I wake wanting him.

My breasts heave and blaze.

My heart chars.

Untitled by Murasaki Shikibu (974-1031), from Women Poets of Japan

This life of ours would not cause you sorrow

if you thought of it as like

the mountain cherry blossoms

which bloom and fade in a day.

Untitled by Saigyō (1118-1190), from A Reader's Guide to Japanese Literature

Gazing at them,

these blossoms have grown

so much a part of me,

to part with them when they fall

seems bitter indeed!

Shinkokinshū, IV: 361 by Jakuren (d. 1202), from Japanese Court Poetry

Sabishisa wa

Loneliness –Sono iro to shi mo

The essential color of a beautyNakarikeri

Not to be defined:Maki tatsu yama no

Over the dark evergreens, the duskAki no yūgure.

That gathers on far autumn hills.

Untitled by Bashō (1644-1694), from Basho: The Complete Haiku

nozarashi o

weather beatenkokoro ni kaze no

wind pierces my bodyshimu mi kana

to my heart

Untitled by Bashō (1644-1694), from Basho: The Complete Haiku

yagate shinu

soon to diekeshiki wa miezu

yet showing no signsemi no koe

the cicada's voice

Untitled by Kobayashi Issa (1763-1827), from A Reader's Guide to Japanese Literature

Beneath the bright

Cherry blossoms

None are indeed

Utter strangers.

Untitled by Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902), from The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature

mihotoko mo

Buddha too –tobira o akete

he's opened his altar doors,suzumi kana

cooling off

The Oyster Shell by Kambara Ariake (1876-1952), from The Poetry of Living Japan

An oyster in his shell

Lives in a boundless sea,

Alone, precarious, limited,

How miserable his thoughts . . .Unseeing and unhelped,

He sleeps behind a sheltering rock.

But in his wakeful moments he must sense

The ebb and flow of the infinite deep.Though the turning tide at dawn

May flood in to its height,

The oyster's being, destined to decay,

Is tied to a narrow shell.The evening star, so luminous,

Turns the waves to crests of corn:

Us it reminds of a distant dove –

Of what avail to him?How sad a fate! Profound, unbearable,

The music of the ocean

Still confounds him day and night.

He closes tight his narrow home.But on that day of storm

When woods along the sea are shattered,

How shall it survive – the oyster shell,

His shelter, left to die a destined death?

Late Autumn by Hagiwara Sakutaro (1886-1942), from The Poetry of Living Japan

The train was passing overhead,

And my thoughts meandered into the shade.

Looking back, I was surprised to find

How my heart was at rest!

Streets were strewn with the autumn sun's last rays,

Traffic crowded the highway.

Does my life exist at all?

Yet in the window of a humble house,

Along a back street where the smoke still hung, Purple hollyhocks were blooming.

Untitled by Katsura Nobuko (1914-2004), from A Long Rainy Season

My mother's soul

viewing the plum blossoms,

returning at night.

Untitled by Itami Kimiko (b. 1925), from A Long Rainy Season

What lives in the lake

filled with a blue

that has no name?

Concerning Obscenity by Shuntarō Tanikawa (b. 1931), from The Selected Poems of Shuntarō Tanikawa

No matter how pornographic a movie

it can't be as obscene

as a couple in love.

If love is something human

obscenity too is something human.

Lawrence, Miller, Rodin,

Picasso, Utamaro, the Manyō poets:

were they ever afraid of obscenity?

It is not a movie that is obscene

we are the ones basically obscene

warmly, gently, vigorously,

and with such ugliness and shame –

we are obscene

days and nights obscene

with nothing else, obscene.

Final Thoughts

I suspect most of us have felt the sting of unrequited love. From reading her poem above, I know that Ono no Komachi once felt the same pain: "My heart chars." Like the other poems I chose, these words speak to me in a profound way, despite being written well over a thousand years ago by a woman from a culture very, very different from my own. This to me is the true beauty of poetry: its ability to reach across time and space to touch those who read it. Likewise, I hope you enjoyed the poetry here, and that some of it spoke to you as well. If you are interested in learning more, seek out some of the books from the bibliography – they're all great.