Japan’s summers ring in to an annual soundtrack. The melody rides the humid summer breeze from the mountains, down through the forests and along the rivers and roads. Although the musicians prefer the trees, their performance is nearly inescapable. And it’s long. The symphony starts slow in the spring and builds to a crescendo midsummer before fading into autumn.

The best way to soak in the concert is sprawled out, uchiwa in one hand and a cold beverage in the other. A stroll through a park or wooded area is another great way to listen, but the sound can be enjoyed (or loathed) almost anywhere. In fact, I’m discovering that it goes surprisingly well with writing – I’m being serenaded right now, as I type this article.

The song is so synonymous with summer in Japan, hearing it on a TV program instantly reveals the story’s season. If you’ve experienced summer in Japan you know what I’m talking about – semi 蝉 or cicadas.

It’s a Hard-Knock Lifecycle

If you’re from the United States you might be wondering, “How can cicadas symbolize summer in Japan? Don’t they come around every seventeen years or so?” And that’s true – some species of cicada spend seventeen years underground as nymphs. The cicada of these seventeen year broods, or birth groups, are common in the US and surface together in population explosions over limited areas.

But with over one hundred cicada species worldwide, gestation periods vary. Some, like many Japanese species, take as little as a year to emerge from the soil.

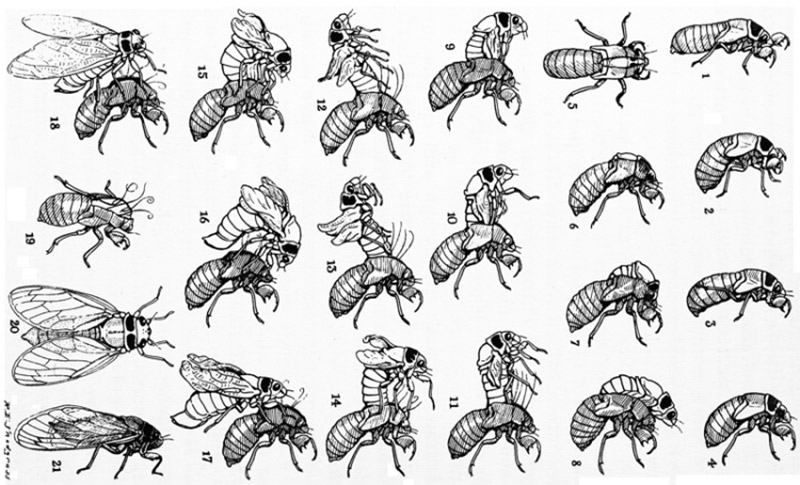

Whether it’s one year or seventeen, cicadas spend the majority of their lives underground. What do they do there? I always assumed they hibernated, but it’s quite the opposite. Once cicada nymphs emerge from their eggs, they stay busy, digging and feasting on tree roots, sap, and xylem. And cicada nymphs must eat well while underground because their time on the surface is limited. Adult cicadas only live for a few weeks, forcing them to focus on adult pursuits – like cicada love-making.

The Cicada’s Song

Soundbite by Σ64.

Soundbite by Σ64

Japan’s summer soundtrack is actually an insect love song – the cicada booty call. Adult cicadas can’t waste a moment searching for mates, hence their deafening cries for attention. And it is loud. Cicadas can reach over 100 decibels or as Clint Rainey of New York Magazine explains, “the decibel levels of a jackhammer.”

How can such small insects produce such an extraordinary sound? John Marris explains,

Male cicadas use their tymbals to produce sound. These are ribbed membranes on each side of the base of the abdomen. Each tymbal is attached by a tendon to a powerful muscle. As the muscle contracts it buckles the shape of the tymbal, much as when the domed lid of a jar is first unsealed, causing a burst of sound called a pulse. When the muscle is relaxed the tymbal pops back into shape. Rapid and repeated muscle contraction produces the distinctive cicada call.

After successfully mating a female will lay her eggs into the bark of a tree. The eggs hatch and the nymphs burrow underground where they feed. Depending on the gestation period, the nymphs emerge from the ground when they are ready to molt – leaving behind hard brown shells when they emerge as adult cicada.

Cloudy With a Chance of Cicada

Why do cicada gestation periods vary? In a survival strategy known as predator satiation, cicada population booms guarantee enough members of the species survive to mate. Julie Geiser of Nptelegraph.com elaborates:

“By emerging in great numbers over a short period of time, the cicada population succeeds by overwhelming predators with its numbers — ensuring that there is a breeding population to carry on the circle of cicada life.”

And when it comes to defenses, sheer numbers represents the cicadas greatest weapon. Other than camouflage, cicadas have no other defense – they can’t bite or sting. Carl Zimmer of the New York Times writes:

“This strategy (predator satiation) has worked so well, that cicadas have lost their other defenses. They even fly sluggishly. When errant cicadas emerge in the wrong year, they are quickly eradicated by birds — along with their errant genes.”

While cicada booms vary by region in the United States, the insects overwhelm Japan every summer, satisfying predators like birds, dogs, and human children while successfully breeding to guarantee the next generation.

Getting To Know Your Cicada

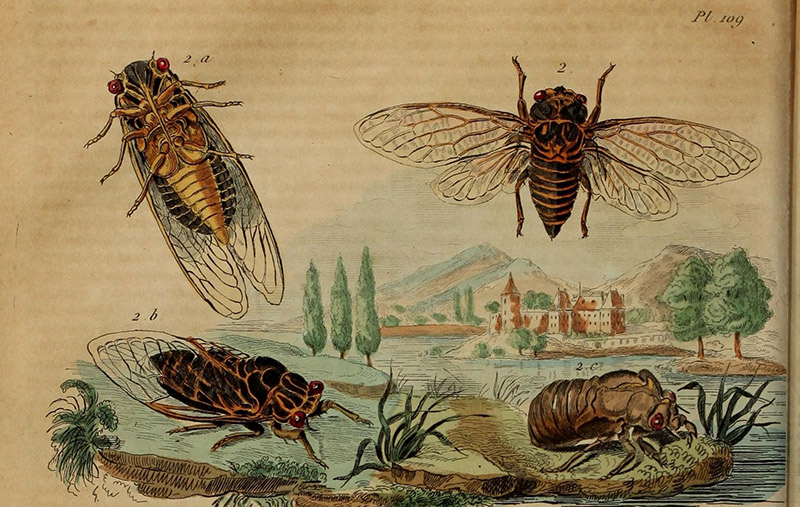

Numerous species of cicada call Japan home, each with its own distinctive size, colors, and song. Cicada education starts during childhood, when catching the insect is a popular summer activity. As a result, many Japanese people can identify a species by song alone.

Kuma-zemi

Song: shaa, shaa

One of the larger species is appropriately named kuma-zemi or bear-cicada. Although its body is mostly black, it’s most distinguishing feature is the bright green tint of the colored parts of its wings.

Abura-zemi:

Song: jii, jiri, jiri

Unlike the clear wings of most cicadas, abura-zemi are noted for their camouflage wings.

Higurashi:

Song: kana, kana, kana

A medium sized cicada, Higurashi has a black, brown and green back with a mostly brown abdomen.

Tsukutsukuboushi:

Song: oushii, tsuku ,tsuku

One of the smaller cicada species in Japan (but longer named), tsukutsukuboushi has a golden head and dark body.

Minmin-zemi:

Song: miin, minminmin

A cicada of the midrange variety, minmin-zemi have fat, short black bodies with bright green tribal tattoo-like designs on their backs.

Niinii-zemi:

Song: chii, chii

One of the smaller cicada, the niinii-zemi can be identified by its light color, and its black and white, sometimes spotted looking wings.

Did You Thank a Cicada Today?

Thanks to an unfortunate case of mistaken identity, cicadas have earned a bad rap in the United States. Perhaps it’s due to their explosive birth numbers, but cicadas are often confused with locusts. And that’s bad news for the cicada as locusts are synonymous with death and destruction. Perhaps it all stems back to the Bible which warns of swarming, creeping, gnawing locusts devouring crops and bringing starvation.

Penn State Department of Entomology writes:

“Early American colonists had never seen periodical cicadas. They were familiar with the biblical story of locust plagues in Egypt and Palestine, but were not sure what kind of insect was being described. When the cicadas appeared by the millions, some of these early colonists thought a ‘locust plague’ had come upon them. Some American Indians thought their periodic appearance had an evil significance. The confusion between cicadas and locusts exists today.”

But cicadas are not locusts or grasshoppers. And even the largest cicada brood seems to cause a negligible amount of damage. “Periodical cicada nymphs feed underground on tree roots,” says Debbie Hadley of Insects.about.com, “but will not cause significant damage to your landscape trees.

Penn State’s Entomology Department found some damaging effects, but they seem inconsequential. Penn State writes, “The most obvious damage is done during the egg-laying process. The slits made by the female in small branches severely weaken them; often the weakened branches snap off in the wind… Feeding by hundreds or even thousands of these insects on a tree root system for 17 years probably affects the tree productivity, although this has never been fully documented.”

Cicada may actually benefit trees, forming a symbiotic relationship. Burrowing cicada nymphs aerate the ground and help water soak into the roots. In The Bizarre Life Cycle of a Cicada, Greg Roza explains how dead cicadas break down providing nutrients directly to to roots. Centuries of cicada and tree coexistence should calm any worries over the “probable effects on tree productivity.”

Cicadas’ most menacing features are their appearance and noise – which population booms only serve to exacerbate. But unlike in the United States where cicada have earned a bad reputation, Japan takes the insect’s annual arrival in stride, earning cicadas a special place in Japanese culture.

Cultural Significance

Cicadas bear deep meaning and a rich cultural history in Japan where they symbolize reincarnation and the cycles of nature. Avi Landau of the Tsuku Blog explains, “Along with the cherry blossom, these creatures, who spend but a few above-ground days living their lives at full throttle before quickly falling away, represent that most quintessential Japanese concept, Mujo 無常, the passing nature of all things.”

Long before the cicada’s summer song became a mainstay in anime, drama, and movies, it frequented the written arts. Avi Landau continues, “Japan’s greatest poets have used these fast-living, short (above-ground)-lived summer icons to evoke the season, as well as sadness or loneliness.”

Oishi no Minomaro’s poem invokes what summer in Nara, Japan’s former capital, must have sounded like in the summer.

Listening to the cicadas’ voices

roaring like a rock-rushing waterfall

I’m compelled to think of the Capital.

Another, by Baijaku, describes power of the cicadas’ symphony and makes Clint Rainey’s jackhammer comparison feel like an understatement.

All shrilling together,

the multitudinous semi make,

with their ceaseless clamor,

even the mountain move.

Who knew the cicada’s song could invoke summer imagery even before the advent of sound recording technology?

Here’s a poem by Matsuo Basho that evokes a feeling of sadness to the fleetingness of life.

A cicada shell;

it sang itself

utterly away.

This one, by Yayuu has a tinge of irony.

Methinks that semi sits and sings

by his former body,

chanting the funeral service

over his own dead self.

Our noisy friend even appears in one of the world’s oldest novels. In Murasaki Shikibu’s novel The Tale of Genji, the main character composes a poem comparing his love-interest’s cast off robe to a cicada shell while evoking some lonely, sad feelings of his own,

Where the cicada casts her shell

In the shadows of the tree,

There is one whom I love well,

Though her heart is cold to me.

The sheer number of cicada references in ancient Japanese literature illustrates the insect’s deep rooted importance to Japanese culture that continues today.

Enjoying Cicada Today

For many children (and some adults, including your child-at-heart author) cicada hunting is a popular way to pass the long summer days. As a result, many Japanese children become cicada experts, learning to differentiate species by sight or sound. School guide books make the knowledge commonplace and further solidify the cicada’s longstanding role in Japanese culture.

But children aren’t alone in enjoying the seasonal insect. Japan is a land of minor fandoms and cicada haven’t gone unnoticed. Most cicada enthusiasts snap photographs, take video or record cicada songs. Just do an internet search or peruse YouTube and you’ll see for yourself – there are plenty of passionate cicada lovers out there!

A New Appreciation

When I’m not outside catching the little buggers with my students, I enjoy taking in the cicadas’ summer symphony at sunset. Just as the day wanes, so will this generation of cicada and the summer they inhabit. Their waning songs mean shorter days and cold weather are not far behind. As the trees grow dark and bear, the cicadas and their shells fade away and I find myself looking forward to the songs of next summer, glad I don’t have to wait seventeen years to hear it again.